The still-effective production features glorious singing by all the principal singers, excellent sets and costumes, and fine storytelling and pacing, led by director Mary Birnbaum, which was marred by a few directorial choices (more on that later).

The story follows the sad path of the hunchbacked court jester Rigoletto at the court of the Duke of Mantua, where women are treated like toys. The jester is haunted by the curse of the imprisoned Monterone, leading him to be even more overprotective of his naïve and innocent daughter Gilda, who is not allowed to leave home except for church, where she is wooed by “Gualtier Malde,” actually the licentious Duke in disguise. The courtiers, thinking Gilda is Rigoletto’s mistress, kidnap her and bring her to the Duke. Rigoletto then starts a downward spiral by paying Sparafucile to kill the Duke at his tavern. Convinced by his sister Maddalena to spare the Duke, he decides instead to kill the next person who comes to the door. Looking to save the Duke, Gilda becomes that next person.

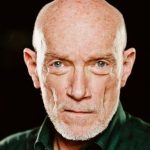

In its history, Lyric has had a number of distinguished baritones as Rigoletto including Tito Gobbi, Ettore Bastianini, Cornell MacNeil, Piero Cappuccilli, and Leo Nucci. Russian baritone Igor Golovatenko joins this list with a performance beautifully sung and acted, bringing a wide variety of vocal colors. His is a smooth and elegant baritone, lusciously bronzed in tone; we occasionally miss the snarl in the sound of Rigoletto’s fury, but his phrasing is elegant and dramatic presence makes him almost ideal in the role. His pleading aria that follows the fury of “Cortigiani! Vil razza dannata” is imbued with the warmth of a father’s affection and his desperation in finding Gilda. His delivery was passionate and very moving.

This was my first hearing of Armenian soprano Mane Galoyan, and I certainly hope it won’t be my last. Her bright, silvery soprano brought charm to the character, and she played the role as a young woman with a bit of backbone to complement her innocence. “Caro nome” is not an aria that I usually admire, but in the hands of Ms. Galoyan, it showed a touch of Gilda’s sexual awakening as well as her delight in first love. Her high notes were clear and easily produced without strain.

The wonderful lyric tenor Javier Camarena seemed underpowered in the first scene (it may be that the chorus of courtiers was unusually loud) but he soon moved forward with his stylish singing. He found a few notes of sympathy and empathy that humanized and deepened the character. He fearlessly flung out high notes, even a high B, with ease and beauty. Even the familiar aria “La donna e mobile” got a flashy rendition, charming and delightful.

The splendid Soloman Howard brought sonorous tone and menace to the assassin Sparafucile, even nailing the preposterously low note at the end of “Sparafucile” that is frequently lost in the orchestra with lesser singers. As his sister Maddalena, Zoie Reams brought her plummy mezzo and strong presence that added much to the famous last act quartet. Baritone Andrew Manea also brought strong presence but lacked the vocal power to make Monterone’s curses come to life.

Enrique Mazzola’s spirited conducting led the Lyric Opera Orchestra in a lively rendering of Verdi’s lush score. As it usually happens with Mazzola, I heard orchestral nuances that I’d never noticed before. He also eschewed moments of flashiness that would call attention to the orchestra, leaving focus on the singers. Michael Black did his usual excellent job with the men’s chorus.

The looming grey and black sets from Robert Innes Hopkins helped increase the sense of claustrophobia in several scenes, especially the small tavern set for Sparafucile (though the set change before that scene seemed to go on forever). Jane Greenwood’s colorful costumes, contrasting with the neutral-colored sets, were appropriate to character and style. I thought Duane Schuler’s shadowy lighting was often too dark; sometimes it was difficult to see faces. Still, the lighting was quite effective in the storm scene.

Director Mary Birnbaum takes something of a feminist view within the male-dominated court, but in the name of giving Gilda more agency, she makes a number of head scratching choices. First, there is a mime happening during the overture (seldom a good idea) showing Gilda at home. Then she opens the door, and there stands a woman, apparently her deceased mother, looking over her. Then, at the end of the opera when Rigoletto is cradling the dying Gilda, her mom makes another appearance, complete with angel wings, and Gilda rises and follows her offstage. Of course, this ending spoils the final father-daughter image that was so important to Verdi in a number of his operas (Luisa Miller and Aida, for example). Also egregious is having Gilda enter Sparafucile’s tavern with a sword, fighting with not only the armed Sparafucile, but also Maddalena and the Duke, so all the characters move offstage and we never see the death of Gilda. It just doesn’t work.

So, all in all, it was a wonderful afternoon of music making from the singers, orchestra, and chorus with a few peculiar moments that annoyed, but did not spoil the performance at all. The production is certainly deserving of the season’s opening opera.

Photos: Todd Rosenberg