Joy tinged with melancholy greeted the opening of Festival O23. Joy because it was a full-scale return of this greatly anticipated event by Opera Philadelphia, which since its inception in 2018 has been a definitive mission for the company in establishing it as one of the leading lights among American companies for vision, innovation, and supporting new work.

The melancholy is due to the recent announcement that David Devan—who since 2011 has been Opera Philadelphia’s General Director, and a major force in the vision behind Festival O—will be leaving the company in June 2024. Effectively, this is the last Festival O he will oversee.

Yet just as the Bible promised, Joy cometh again in the morning. Okay, to be more precise, it came at 8:30pm on Thursday, September 21st at Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater.

That’s when the lights came down at the close of composer Rene Orth’s thrilling 10 Days in a Madhouse, to a rapturous ovation that went on for many minutes. Devan may be leaving the company, but there can be no better living tribute to him than this extraordinary work, which in 90 minutes gives us everything we could want from a new opera—most of all, the sense that this art form has never been more vital and current than it is now.

Orth’s harrowing—yet miraculously, also inspiring—opera is rooted in historical fact. In 1887, Nellie Bly, an investigative journalist before the term existed, checked into a New York mental asylum to see for herself the kind of treatment offered to patients. I probably don’t need to tell you that the horrors she uncovered were more likely to induce madness than cure it. Fortunately for the world, her reporting was a start in affecting awareness and generating significant positive changes.

I can’t claim to be an authority on Bly, but as seen here, through a lean but poetic and powerful libretto by Hannah Moscovitch, the victims are all female patients, for whom “treatment” is virtually non-existent; they are essentially prisoners.

Many of them function here as a small choral ensemble, whose individual stories are cagily sublimated in Orth’s wide-ranging musical language. Sometimes they harmonize beautifully, though ironically those moments also suggest a canny awareness that “harmony” might be a path to get the hell out of there. At other times, their singing is out-of-tune and poorly synchronized; in a few moments that are simultaneously heart-breaking and funny, Orth moves us almost into contemporary R&B which serves as a kind of rebellion.

The entire group, by the way, are clad in rather becoming plaid dresses with aprons, a wry costume choice (by designers Ásta Hostetter and Avery Reed) that invokes images of Emily Dickinson and The Handmaid’s Tale—tidy ladies with a secret life. (Apparently, in an 1887 New York asylum, plaid is the new orange.)

My previous knowledge of Orth’s music was limited to Empty the House, a short chamber opera with a domestic setting that was done by Curtis Opera Theater a few years ago (Orth herself is a Curtis alum). I found that piece theatrically effective, but the growth here in every sense—to a full-length piece with a much larger ensemble—more fully reveals her exceptional gifts. From the first moment, it is an identifiably contemporary work, with some notable stylistic signatures. These include active and sometimes disquieting rustling in the percussion; slides within the musical line; insertion of electronic sounds, including eerie tones as well as the subtle use of amplification. The later device is especially effective in providing a ghostly sense where past and present lose their anchors and seem to merge.

In other points of the score, Orth make effective use of pastiche in diegetic passages. A waltz that sounds both charming and sinister is heard through a gramophone, but also ends up incorporating the orchestra, which here is suspended above a stark, shadowy and fragmented setting (Andrew Lieberman designed both sets and lighting). And the high-lying, sometimes ornamental vocal line for Nellie in particular is clearly meant to remind us of bel canto (and, I’m guessing, particularly Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor)—a resonance through which we understand that this plaintive, high-lying flutiness is how women express distress.

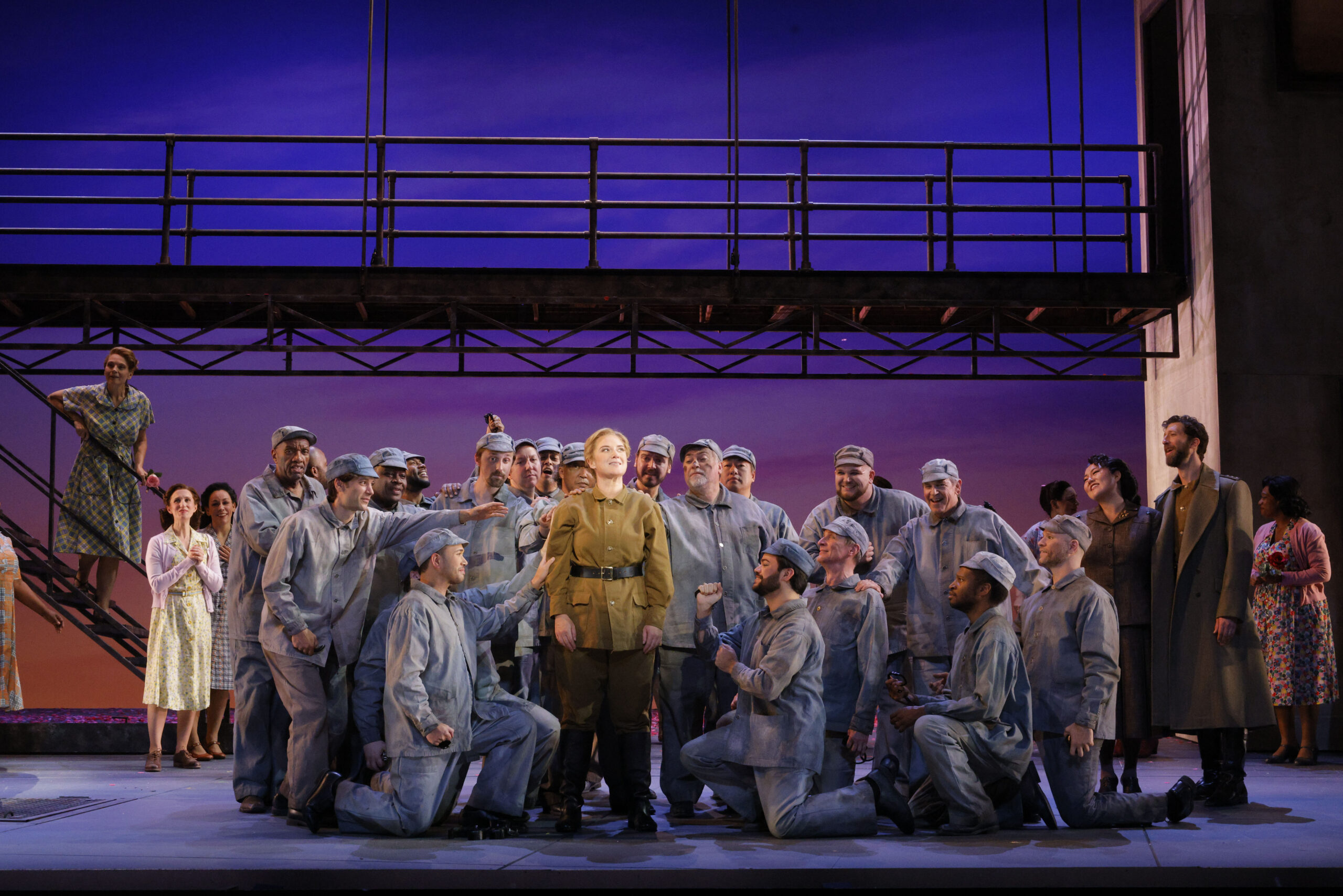

Nellie here is played by soprano Kiera Duffy, in a performance of sensational virtuosity. Duffy’s glorious, silvery singing with its heart-stopping soft high notes is a joy in itself, but more important here, it is always used in the service of fully committed dramatic insight. In 2016, Duffy was a breakout star in Opera Philadelphia in Missy Mazzoli’sBreaking the Waves. She every bit as good here.

Excellent support is provided by Will Liverman, whose mellifluous baritone and grounded stage presence raise the role of the institution’s doctor above stock villainy. As a sinister, mysterious Nurse/Matron, soprano Lauren Pearl is riveting both vocally and dramatically.

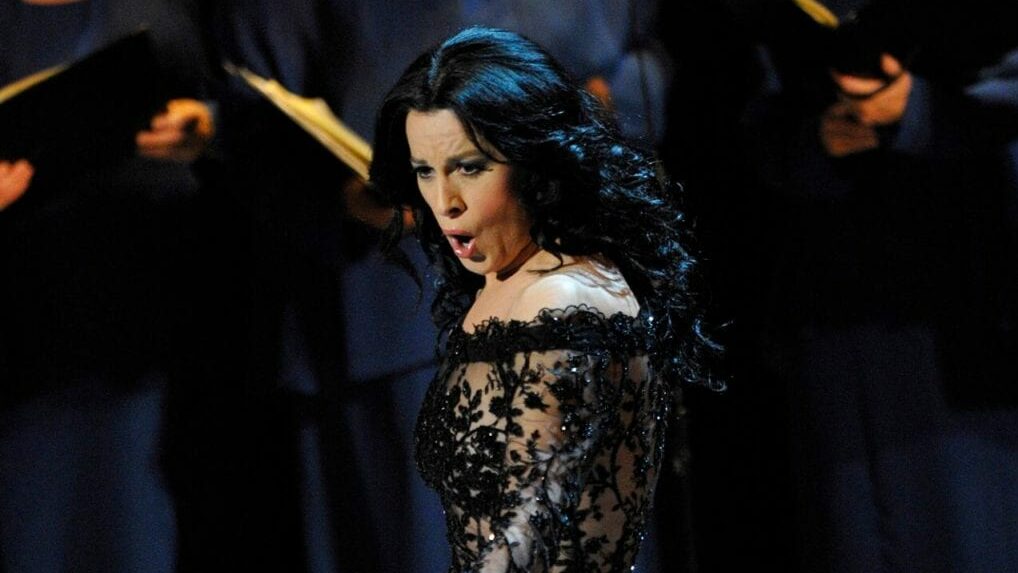

Yet if there’s a breakout star here, it’s mezzo Raehann Bryce-Davis. As Lizzie, an asylum inmate who becomes Nellie’s only friend and confidante, she has the most extended solo sequence—a heartbreaking monologue about what led her to this moment. Bryce-Davis’s titanic vocal endowment across a huge range was reward enough. But more powerfully, here that is coupled with a detailed, nuanced sense of character: imagine Viola Davis with Ebe Stignani’s voice, and you’ll have some sense of the effect. She has engagements coming soon at the Met and with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, among others. If you are anywhere near, get your tickets now.

Orchestral playing led by conductor Daniela Candillari was top-notch. A spare and visually haunting prodution by director Joanna Settle proved a worthy setting.

Is 10 Days in a Madhouse perfect? Pretty close, but one small though telling details sticks with me. The final moment is a summation by Nellie of her experience. (By the way, the piece is otherwise cleverly structured in reverse chronological order, which adds a poignant overlay.) In this section, Orth provides Nellie again with a high, floating vocal line we’ve heard her use earlier. It’s beautifully delivered by Duffy… but it doesn’t ring true for me. This musical style, evocative of Lucia and more generally suggesting bel canto distress, is the language of Nellie’s invented “madness.” Surely, when we meet her as a journalist, she should sound different? Personally, I’d love to hear her end in spoken dialogue—a powerful, plainspoken recounting of the facts. I also think Duffy, a born actor, would knock it out of the park.

Festival 023 certainly is off to fine start.

Photos: Dominic M Mercier

Comments