We encounter the statue, whose hips smile and whose stone “glistens” like fur, only to find that it has encountered us: “For here there is no place that / does not see you. You must change your life.”

The final directive, which comes as if from the statue itself directly into our minds, has long struck me as a particularly powerful representation of an artistic encounter. It is not that just we see, but that we are seen, and that, having been seen so fully, we are impelled to change. The line, like many of the poet’s final lines, appears as if from nowhere, but then feels inevitable.

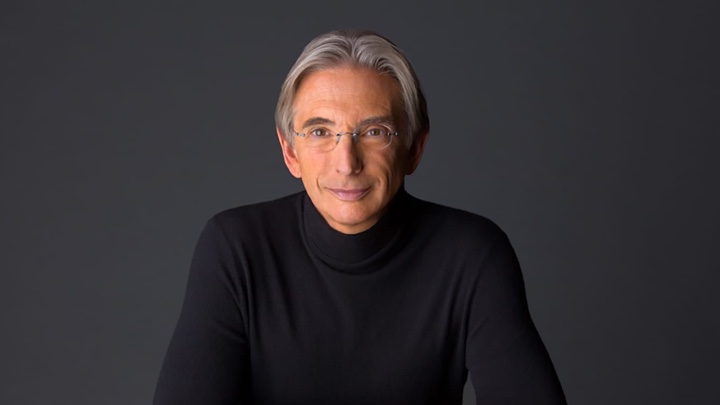

Michael Tilson Thomas, conducting his own Meditations on Rilke and the Schubert Symphony No. 9 in C major, last night with New York Philharmonic, delivered some personal meditations of his own, on his father, on Bernstein, and on a life in music.

Described as a combination of Schubert, Mahler and Berg filtered through ragtime and cowboy songs, Meditations on Rilke wears its mishmash of stylistic influence and its fundamental romanticism on its sleeve. There are moments when the mixture of styles and subject don’t fully emulsify, but with texts like Rilke’s and with MTT’s clear and loving approach to phrasing, overall, the settings are quite satisfying.

The wind section is especially well-employed, for both lyrical and humorous purposes. Baritone Dashon Burton was occasionally somewhat hard to hear over the orchestra, but was a beautifully expressive and sensitive interpreter, very close reader of his texts. Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke had an easier time carrying in the hall, her surprisingly light and swiftly-spinning tone paired with an easy, serene delivery.

Cooke also had the bulk of the poet’s aspirational lines, including these, here translated by Robert Bly:

I live my life in growing orbits,

which move out over the things of the world.

Perhaps I can never achieve the last,

but that will be my attempt.

It ends with this:

I still don’t know if I am a falcon, a storm

or a great song.

Rilke’s poems are all in motion: widening or wheeling or walking out. Or falling. But this motion is slow enough to take in through stillness, with a balance of mortality and hopefulness in each hand. MTT’s settings feel more than just a reading of Rilke, but a highly personal gift, in return; like the ekphrastic turn in “Archaic Torso,” they acknowledge musical influence as beginning somehow by being seen by the music and poetry one loves, not just the study of it.

They also posit sincere, expressive admiration and love as the path to excellence, not as qualities to be sidelined in favor of grit, irony, and critique.

This was a wonderful concert because MTT approached every moment of it with an air of expansiveness and gratitude. Perhaps after his recent struggle with brain cancer, MTT has leaned even further into exuberance. For all the contemplativeness of Rilke, in which mortality sharpens each moment, the night was shot through with joy.

MTT spoke with frankness and at length of his father, and for appreciation for the artists who shaped him, and the ones with whom he shared the stage. Because of this grateful sincerity, the New York Philharmonic felt suffused with a gentle warmth and played with welcome ease. The strings, especially, felt nearly incandescent during the second half in which they tackled Schubert’s physically demanding Symphony no. 9 in C Major.

Players smiled onstage, swayed, and everyone looked relaxed and like they were enjoying themselves thoroughly. But this looseness didn’t lapse into sloppiness—this was a technically excellent performance, but without the stress-sweat and tension that can occasionally seep in, making an ensemble feel chilly and sterile.

MTT’s conducting is mostly a series of suggestions. Ranging from a flutter of the fingers to the two-handed swing of a baseball bat(on), it never felt controlling or overbearing; it was as if he invited his players to fill the space between his gestures with complete confidence that what would emerge was beautiful.

That trust allowed for a beautiful tapestry of color and texture to be spun, unconstrained and unhurried from the orchestra. For us, however, time moved swiftly. Schubert’s 9th symphony is nearly an hour long, but I never felt tempted to check my watch.

At the end of the concert, MTT stopped the applause and redirected it away from himself and onto the string section; citing their athletic stamina and tight playing in a piece which demands their near relentless attention. The players, exhausted but looking somehow younger, beamed at us as we cheered for them.

It reminded me so clearly of the director of my undergraduate wind ensemble (who perhaps has studied with MTT at some point or another or perhaps is just a fan and kindred spirit), who, after conducting any concert would always be the first to offer a “Bravo.” This was somewhat divisive amongst us, I recall: was it self-indulgent or sincere?

I always read it as genuine, a public display of his pride in his ensemble of whom he would always be the biggest fan. This was good pedagogy, for both music and life, I think, because it positioned joy and gratitude as the wellspring of good music-making and insisted on the open expression of both by the ensemble’s leader as an ethical imperative.

Perhaps listeners less fundamentally sentimental than I would find all this a bit over the top, or find MTT’s speeches either unforgivably earnest or hopeless self-indulgent and his informality inappropriate. But I left wanting to practice, to make music with other people—not out of guilt or perfectionism —but because I was reminded how music and poetry can tell us with poignant, unexpected joys.