The performance is, pardon me, an abortion. I know cuts especially of bel canto operas were standard in the ‘50s, but this goes way beyond standard cutting. I’ve always dismissed Karajan’s later EMI recording since it uses the 4-act version, but taking just one scene as an example, the Garden Scene (Act II, Scene 2 in the original version), there are cuts in the first chorus, one verse in the Veil Song ruling out its relevance to an event later on in the opera, more cuts for the chorus, half of Posa’s ballade gone, several measures missing from the Carlo-Elisabetta duet – some of the most glorious music Verdi ever composed for a duet, one verse for Elisabetta’s romanza thereby eliminating her subtle retaliation to the King for his insult.

And on it goes. Did I mention that Karajan has now changed the page Tebaldo from a part written for a female soprano to a male baritone? Half of “Tu che la vanita” is gone and most of the final duet. It’s a real shame because this ’58 performance is so exciting otherwise. If Karajan thought so little of the opera, then why do it at all?

That same philosophy applies to his 1979 EMI recording, the cuts were restored as per the 1884 Milan version, but the 1986 video again from Salzburg shows Karajan reverting to the same cuts. This was some 16 years after the discovery of the lost materials and is now just inexcusable. Verdi sanctioned many cuts, and as he said right from the time of the Paris première, if anything was going to be cut, he was going to do it himself.

In Karajan’s defense, the same cuts were made in Bing’s famous 1950 production at the Met and I’m guessing they continued to be until the new production with Levine conducting came along in 1979 when even the “Hunters” scene was included with the original Act I.

The reason I bring this up now is that with all these cuts, Karajan replaces the new (1884) introduction to Act III with the original opening with the trading of the masks between Elisabetta and Eboli. I have nothing really to go on but I thought this was one of the originally cut and lost sections that were discovered in 1969/70 yet this performance was 1958. It goes without saying that HvK abridged this scene also. I have found no explanation of this anywhere, but in the back of my mind, I seem to recall that this scene did escape the dust bin.

One has to assume that a certain amount of time has elapsed between Acts II and III; certainly enough for Posa to have established himself as the “favorite” of the King and a resentment of that to build within the court.

In any case, we are now in the Queen’s garden of the Palace in Madrid. It is the day before the coronation of King Philip. Coronation? What coronation? He’s been king for at least a decade. Whatever. The political rally of the Vienna version makes more and more sense.

Of all the cuts that Verdi made, cutting the original opening of Act III makes the least sense. Gone is the explanation as to why Eboli is wearing Elisabeth’s mask and why Carlos mistakes Eboli for Elisabeth. Also, Eboli writes Carlos a note telling him to meet her in the garden. Without all this exposition, the new Act III opening makes no sense. Perhaps time. But the opera has already run shorter than this essay so what difference does it make?

The ballet follows. Why anyone would want to cut this wonderful music, or for that matter the ballet in any opera totally eludes me. If nothing else, ballet was one of the primary features of grand opéra. The usual argument is that it stops the action. Phooey! It should be part of the action.

In Verdi’s other “French” operas, or at least the ones he did new versions of for the Paris Opèra, the composer might have grumbled about doing it but he never failed to provide exciting music for the new Macbeth, Jérusalem, Il Trouvère, Les vêspres sicliennes, and Otello.

The third act is devoted to spectacle; it starts with the ballet and ends with the immense auto-da-fé. This grand ballet is set in a glittering submarine cave; its subject is the discovery of the famous pearl, La Peregrina, Philip II’s most splendid jewel.

In time it became the property of Napoleon III and later belonged to Elizabeth Taylor. The end of the ballet incorporates the Queen, but in the event, places were changed and Eboli gets her moment in the spotlight so to speak.

One of the arguments against including the ballet is that one would lose the new prelude to Act III which is of especially high quality. My feeling would be to include them both with the new prelude following the ballet; that brings us back into the garden and allows time for Carlos to receive Eboli’s note.

In the confrontation that follows, Carlos’s private life approaches its catastrophe when the vain and jealous princess resolves to denounce him to the King. In the following scene, Carlos’s public life reaches a similar crisis. Other than the intro and ballet or the new prelude, this third act remained mostly unchanged from the Paris première.

The second scene takes place later that morning and, according to the corrected score, in front of the basilica of Our Lady of Atocha on the right, and inaccurately with the palace on the left. In celebration of Philip’s supposed coronation, an auto-da-fé (“an act of faith”) was held.

This was a Roman Catholic ritual of public penance for condemned heretics when the Inquisition had decided their fate. The most extreme punishment imposed on those convicted was execution by burning at the stake, but this was only part of the rite. Auto-da-fé involved a mass, prayer, a public procession of those found guilty, and a reading of their sentences. They took place in public squares or esplanades and lasted several hours; ecclesiastical and civil authorities attended. The last public auto-da-fé took place in 1691.

Apart from the question of the monk and Carlo V, another problem I have always had with the work is una voce dal cielo (the “voice from Heaven” – and I don’t mean Tebaldi). This is a supernatural element that is not based on any reality; in more ways than one, it certainly comes from nowhere.

Again, leave it to the execrable Vienna production: an “opera diva” steps forward, score in hand, and sings it like she was singing the National Anthem. I’m sure there are better solutions for this. Point of interest: one of the six Flemish deputies in the première was a student from the Paris Conservatoire, Victor Maurel, the future creator-to-be of Iago and Falstaff.

Scene 1 of Act IV, sometimes referred to as the “closet” scene, takes place presumably the next morning shortly before dawn in Philip’s study. After the huge public scene of the previous act, this is the “private” act. The approximate 20 minutes that comprise the beginning of this act, Philip’s monologue and the Grand Inquisitor scene, comprise some of the 20 greatest minutes in the realm of opera.

Verdi got it right the first time, and never made any changes. The primary two reasons that the 1966 Solti recording is near the top of the best list are the quintessential performances of Nicolai Ghiaurov and Martti Talvela as the King and the Inquisitor. Their live performance in a 1970 Vienna performance is even more remarkable and show them to be the prime interpreters of their roles.

I was fortunate to have been able to attend one of the five performances they did in the fall of 1968 at the Met under the rare appearance of the supreme Don Carlo conductor, Claudio Abbado. It was my first time seeing the opera but I was very familiar with it as I had played the then new Solti recording over and over. I remember being very disappointed in the auto-da-fé scene – the music is so filled with action yet the staging was totally static.

But that all changed with the beginning of the next act and all the incredible power of the scene was brought out in these ideal performances. It remains one of my most cherished memories. I should add that between the five performances, Talvela found time to squeeze in three Hundings in a Walküre with Nilsson, Crespin, Ludwig, Vickers, and Stewart led by Karajan. Those were the days!

Like Philip’s scene with Posa, his monologue and the scene with the blind Grand Inquisitor are dramatic events that Verdi expressed in a new musical language, one that soars above merely euphonious melody. Verdi was adamant in retaining this scene from the Schiller and made strongly clear that the Inquisitor be very old and blind.

Verdi didn’t risk spelling out the anti-clerical metaphor in greater detail. He enhanced the importance of the Inquisitor making him brutally implacable as well as grandiose and his music describes his heavy and menacing presence. The blind fanaticism of the aged monk contrasts with Posa’s political idealism and by the end of the scene, Philip is compelled to give up his “favorite.”

In attendance at the original French production, the Empress Eugénie, the consort of Napoleon III, most strongly objected to Philip’s saying to the Inquisitor, “Tais-toi, prêtre,” which I learned in high school French clearly means “shut up priest.”

Obviously this phrase was totally unacceptable to an Italian audience and was softened to “Non più, frate” or “No more, friar” for the Italian premiere. Likewise, the dialogue continues with: “Prêtre! J’ai trop souffert ton orgueil criminel!” “Priest! I have suffered too long your criminal pride!” which was changed to “Frate! Troppo soffrii il tuo parlar crudel.” “Friar, I have suffered your cruel words too long.” That’s all understandable.

What isn’t is the ambiguous, at least for me, statement the Inquisitor makes: “Why did you invoke the shadow of Samuel? I have given two kings to this mighty empire; the work of all my days, you wish to destroy?” In all the synopses I have looked through, all of them avoid comment on this.

Budden is little help. He says that it is “a key phrase in Schiller reminding us that the paradigm of Saul, David, and Jonathan underlies the relation of Philip, Posa, and Carlos.” Huh? In the Bible, Samuel was known as the kingmaker. He anointed Saul and David. Beyond that, I don’t get it. I probably need to go to a prêtre myself. To add to the confusion, what I do know historically as stated earlier is that the King appointed the Inquisitor, i.e., Philip II appointed Espinosa whose service was considerably shorter than Philip’s.

After Philip’s acquiescence for Posa’s death, a weakness I find in the following scene with Elisabeth, Eboli, and Posa himself is that after Philip’s realization regarding Posa, no reference or reaction to it is allowed for in the following quartet. This quartet was revised primarily by shortening it. It’s a shame because the early version is a more concerted number and though perhaps not quite the equal of the Rigoletto quartet, it is immensely and far more moving than the revision, one of the most beautiful moments of the score.

Following the quartet and Philip’s and Posa’s exit, another huge cut was made. In fact, this was the first cut to be made in Paris, possibly because it dealt with the adultery of Eboli and the King, a generally taboo subject for a bourgeois 19th century audience.

Another reason given is that it was reported that Marie Sasse, the Elisabeth at the première was in a nasty rivalry with Pauline Gueymard, the Eboli; during the preparation of the opera it became so heated that at one point Verdi refused to attend further rehearsals.

What a shame because the duet is exquisite – very Belliniesque. Like all the other cuts, not only is music by the mature Verdi lost, but important dramatic structure. When Eboli’s second “sin” is confessed, Elisabeth is so shocked she is at a loss for words and simply walks out. It is for that conniving Lerma to inform Eboli that she is exiled.

Between the Closet scene and the following Prison scene, there is more offstage, unseen action than we have seen onstage in the entire opera. Everyone has been busy. Posa in order to save Carlos has arranged to let Carlos’s politically sensitive documents be found on himself proving that he, Posa, is the traitor. Now Posa is meeting with Carlos in the prison knowing that his life will be sacrificed.

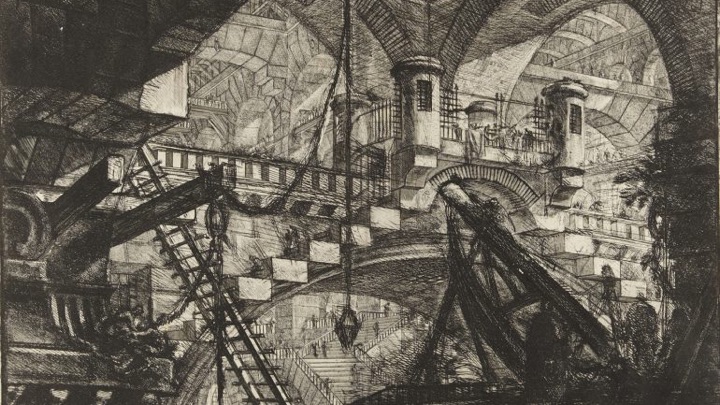

Before that, Posa has also met with Elisabeth who (inexplicably) also shows up at the prison. Eboli has been stirring up the populace in order to incite a rebellion in the prison during which she will abet Carlos in his escape. The King has come to his senses and comes to the prison to free his son. The Inquisitor has arranged to have Posa killed and also shows up in the prison. This is one mighty big prison cell! In my mind, the only way I have come to justify this is that it must have been one of the prisons depicted in the famous Piranesi etchings of Spanish prisons.

With the last revision, the Prison scene is reduced almost to just Posa’s two magnificent arias. The original scene is twice as long and the cuts, also made for the Paris première, were made to save time. It is well known that this is the music that Verdi later used for the “Lacrymosa” in his Requiem.

The duet for Carlos and Philip shows both men standing united in grief before a man who has inspired them in opposite ways. It explores emotions aroused by Posa’s death more profoundly than the brief exchanges to be found in the revised score – the King mourning his only friend whom he sacrificed, Carlos resolving with his friend’s death shall not be in vain. We learn more of the solitary monarch’s dependence on the only man who had dared to speak to him frankly.

Unquestionably, both this cut and the Elisabeth-Eboli duet should be restored. Perhaps not so much the conclusion of the scene, the insurrection, or the “sommossa” as Verdi refers to it. Both versions are confusing; more information is provided in the extended original version, the other being more concise.

Eboli’s resolution to free the Infante is carried out too late, since by the time of the “sommossa” he has already been set free by Philip; nor is it clear to the audience that the riot is her doing – Eboli just gets lost in the crowd; in the score it says that she is disguised as a page – that hardly helps focus on her.

The difference in time between the two sommossas is four and a half minutes versus three and a quarter. The plus of the earlier version is that Eboli’s presence is stronger than the three words she is allotted in the revision (as often as not, she is just cut out of the scene) and Philip is shown to stand up to the rebellious crowd.

The last act, Act V, is again at the monastery of Yuste, same as in Act II. It’s supposed to be the next day which could not have been really possible in that time unless everyone had a series of very fast horses. Regardless, the act opens with one of the great soprano arias in the repertoire in which Elisabeth reminisces on what transpired in Act I and is almost meaningless if Act I has been cut.

Her mind is a confusion of memories – of France, Fontainebleau, the Spanish gardens, and other dreams; she too longs for death. As mentioned at the beginning, this moment in the early composition of the libretto was meant for Carlos, but the inadequacies of the original tenor led to it going to Elisabeth.

The ensuing duet again is filled with themes and reminiscences of Carlos and Elisabeth’s original meeting and much is lost without knowing their music for that. The original version of the duet is very episodic and Verdi revised it smoothing out the rough edges to make it more of a whole. Definitely the revised, but uncut, version is the preferred.

There are two very different versions of the conclusion of the opera. The second version, the one we know, is very quick: the King with the Inquisitor enters catching his son and his wife together. The King famously says to the Inquisitor, “I have done my duty, now do yours.”

He also says that a double sacrifice is needed; whether he means Carlos and Posa or Carlos and Elisabeth is open to debate. Carlos draws his sword to defend himself when a “mysterious figure” emerges from the tomb of Carlo V. He supposedly drags Carlos into the tomb and the curtain falls on probably the weakest, most ineffectual ending of any opera.

In the original version, there is a chorus of the monks and a brief trial very similar to the one in Verdi’s next opera, Aïda. The original ends very quietly and most profoundly. The new ending is noisy and allows Caballé to hold her high B until the curtain comes down! I have found that musical works that contain a lot of bombast, such as Tchaikovsky’s 6th, Strauss’s Don Juan, or Wagner’s Ring end very quietly and it’s a bit of a letdown. However, with Don Carlos, I lean slightly more towards the original, quiet ending and find it very moving. But I do miss that high B!

The ending has always been something of a problem. At the end of Act IV the Church seemed to be triumphant; at the close of the opera, the Inquisitor’s voice thunders again—but a higher power – the ghost of Carlo V? – arrives to contradict him.

Even Verdi himself, 15 years after the premiere would still ask his librettist about it. In an essay by Gilles de Van, “Off the Beaten Track,” in the ENO Don Carlos Guide, it states “in a famous letter written in 1883, Verdi listed all the historical falsehoods and inaccuracies in both the opera and Schiller’s play.” This letter is apparently so “famous” that no one has bothered to publish it, at least that I can find. However, I did find the following correspondence regarding the Carlo V situation:

On a trip to Paris in 1882, Verdi was considering the revision of the opera with the aid of Charles Nuitter, archivist of the Opéra and with Camille du Locle, one of the original librettists and now manager of the Opéra Comique and with whom Verdi was not on speaking terms over failure to pay royalties.

Verdi wrote to Nuitter: “Charles V’s being alive has always jarred upon me. If he is alive, how is it that Don Carlos does not know it? Moreover, (always supposing him to be alive) how can Philip II be an old man as he describes himself. We must decide whether it suitable or not to omit this Monk who is half ghost and half man; or whether instead it might not be better to transform this Monk into an old colleague of Charles V, long since dead: a monk who could come to pray at Charles V’s tomb.”

Fortunately, this poor idea did not come to fruition. Du Locle’s notes on the projected modifications said:

The death of Charles V, which was for a long time kept hidden, is not a date in history [later proved otherwise], since for many years he had disappeared from the world’s stage on which he had played so large a part. He himself, retiring to the monastery of Yuste, liked to wrap himself in a kind of funereal mystery. He had his obsequies celebrated with great pomp, attending them dressed in a monk’s robe, hidden amid the friars of the monastery. This is more than enough to justify the operatic role which the authors of the Don Carlos libretto have assigned to the great Emperor. … To suppress the character of Charles V would be to diminish the grandeur and effectiveness of the introduction to the new first act, so striking from a musical point of view and would be a more than regrettable sacrifice. If the monk were to become an ordinary monk, how could one justify the journey, made twice during the course of the drama, by all the Spanish court from Madrid and from Valladolid to Yuste, deep in the mountains of Estremadura. … The author of this note thinks it desirable that the role of Charles V should be retained. Perhaps the secret of his life continuing among the monks, while he prays beside his empty tomb, should and could be better explained … then at the end, after Carlos is sentenced, Charles V could appear perhaps having reassumed the Imperial attributes; he could intervene like a God at the denouement of a classical tragedy, to conclude the action either by saving or condemning Carlos.

In actuality Carlo V was already dead, but it is easiest for us to ignore the dates and use reality to presume that he had been alive all these years living at San Yuste in monastic retirement. Therefore, Carlo V appears and snatches his grandson from the same hostile world from which he had escaped. Or, is this monk or ghost a representation of death? In any case, no one could construe it as a ‘happy end’ – what we see is certainly the “disappearance” of Don Carlos.

The exact wording of the original states: “Carlos, defending himself, retreats towards the tomb of Carlo V. The monk appears, draws Carlos into his arms and covers him with his mantle.” The revised states: “The monk appears. It is Carlo V with his mantle and the royal crown.” In both versions the Inquisitor says: “It is the voice of the Emperor.” Four ‘familiars of the holy office’ say, “It is Carlo V.” Philip says,“My father.” And Elisabeth hits her B.

Here is a list of how some different productions end taken from many videos I have:

- La Scala 1978 (Abbado; Domingo)—Original ending. There’s a procession of wagons with symbols/implements (?) of the Inquisition; Carlo V wearing crown rises up through a trap in the floor, envelops Carlos in his mantle and they sink back down.

- – Met 1980 & 1983 (Levine; Scotto/Freni, Moldoveanu/Domingo respectively)—Same staging in realistic setting. Carlos stands with sword in hand, gates magically open, and he walks through them; no monk, no Carlo V – an easy cop-out.

- – Salzburg 1983 (Karajan; Carreras)—At least this time Carlos fences. Again, the tomb has magic gates. Carlo V appears as king without crown. Carlos walks through the gates in a daze.

- – Paris/Chatelet 1986 in French (Pappano, Luc Bondy; Alagna)—Combined ending starting with the revised then switching over to the quiet original ending without the trial. There is no fighting. The tomb is a massive stucco type thing. A panel of it opens, a hand reaches out and draws Carlos in. A stupid, non-ending.

- – La Scala 1992 (Muti, Zefferelli; Pavarotti)—Lavish production (duh!). Whoa! Not sure what happens here. Of course there’s no sword fighting – this is the Big P. The friar walks out and sings his lines holding a huge, bejeweled, very Catholic cross. The Inquisitor and Philip say their lines – it’s the king, it’s the emperor, it’s my father – except it isn’t because after Elisabeth very understandably says “Oh, heavens!” some huge something rises up – is it the tomb? is it a frieze? whatever it is, it’s very gold and gaudy and very Catholic. It’s possible Carlo Quinto could be in there somewhere. There’s no clue as to what happens to Carlos. Whatever – it’s impressive!

- – Vienna 2004 in French (de Billy; Vargas)—Not only in French, this is the complete original without any cuts, just as Verdi wrote it. At least the music is. Now try to stay with me here… Philip and his henchmen (or is it the Inquisitor’s gang?) are in modern dress. Carlos and Elisabeth in period. The trial is held. Carlos runs back and forth, is beaten up by the gang while Liz is tossed hither and thither. Both end up on the ground as the gang surrounds them with cigarette lighters. All of a sudden the back wall opens up and the friar walks out while the gang scatters. We already know from the beginning that this is Carlo Quinto since he keeps his crown underneath his cassock. He slaps Philip across the face, takes – here’s a new twist – BOTH Carlos and Liz by the hand and leads them back through the wall, knocking out Philip on the way. As the wall closes and the music quietly fades, we hear the blind Inquisitor tapping his cane which we still hear after the lights have gone out. Remember “Eboli’s Dream”? I’m not making this up, you know!

- – Amsterdam 2004 (Chailly; Villazon)—Too complicated to explain the production here! This is the one where Carlos is definitely a lunatic. Carlos and Philip start to fight; as the Monk/CarloV’s voice is heard and not seen, Carlos grabs his father sword, stabs himself, and falls dead at his father’s feet. This is by far the best ending, but the suicide ONLY works if we know that Carlos is insane and being played with extreme intensity by someone of the caliber of Villazón.

- – ROH 2008 (Pappano, Hynter; Villazon)—This time Rolando gets to do a lot of sword fighting, unfortunately the guards kill him and he dies in Elisabeth’s arms. The friar appears as a friar but wearing Carlo’s crown.

- – Met 2010 (Nezet-Seguin, Hynter; Alagna)—The only difference is that the friar does not wear the crown. These Hytner endings seem an excellent solution, even though not what Verdi wrote.

- – Salzburg 2013 (Pappano; Kaufmann)—This is the most complete of Pappano’s versions. And it clearly is “Pappano’s version.” It’s a pick-and-choose: one from column A, two from column B. It certainly lacks consistency, and I have no problem with that concept; only with some of the choices. The ending uses the revised ending but switches to the original quiet end after Elisabeth’s “Ciel.” There’s a lot of sword play until the Friar’s voice is heard. Carlos turns to see the tomb open and Carlo V walking out of it but totally in gold, even his face – I assume then it is a singing statue … the Commendatore? The statue drags Carlos into the tomb. Everyone is in awe except for the Grand Inquisitor who faints. Or dies. Whatever.

One more variant needs to be mentioned, though this is not a video: the wonderful, albeit 4-act version, from Vienna with Corelli and the incredible Ghiaurov-Talvela encounter. This version features a tradition specific to German theaters: Carlo commits suicide instead of being rescued by Carlo V in order to be faithful to the original Schiller work, regardless of the fact that it is no less of a contrivance than Verdi’s but Verdi’s resultant dénouement is regarded as an insult to a national poet.

The biggest problem though is that after Carlos’s final line, a cut of 13 measures is made that not only eliminates the Friar/Emperor problem, but all the lines of the Friar, the King, the Inquisitor, and Elisabeth’s final B. A distressing choice!

As you can see, everyone has their own idea of how the opera should end regardless of Verdi’s or his librettists’ intentions; since they had their own issues with the end, there is justification for a director choosing his own version.

My feelings are that the opera’s original endings are like those end-of-the-season cliffhangers and you don’t really know Carlos’s fate. It’s not decisive; in theatre terms, it just doesn’t play. I also totally dislike adding a supernatural ending to what has been a very realistic work (barring that thing with the Celestial Voice) and one based on historical facts.

Therefore, Carlo V rising from the grave strikes me as ludicrous. That leaves the two versions both coincidentally with Rolando Villazon. In his earlier version, he is definitely a wacko and his suicide is totally in character.

However, in the German tradition which Corelli plays and I assume Corelli only plays it in an heroic mode, a suicide is totally out of character. That leaves the other Villazón portrayal, the ROH/Met version (with Alagna in the latter) where Carlos is killed fending off the guards and especially moving when he dies in Elisabeth’s arms. So this would be my preferable ending. It is decisive and completes the arc of Carlos’s life from relative youth to his death.

I think I have also made it pretty clear that nowadays the complete original version is the preferred, perhaps substituting some of the revisions. Audiences in 1867 were not inured yet to Wagner and despite the longueurs of Meyerbeer could not sit in a theater for the five hours or so including intermissions that a complete Don Carlos would take.

Today, we – at least some of us – are willing to do so. I would prefer to hear it in French because it is right! but I’m practical enough to prefer the sound of it in Italian, especially since the best singers for the parts tend not to be the best singers of French.

As for an ideal version, I think it makes more sense not to go with what were Verdi’s final thoughts, i.e., the “mashup” of the Modena version and then restore some of the cuts, but to work from the other direction: start with Verdi’s original before any cuts were made and then substitute most of the revisions, in particular the final versions of the two Posa duets and especially the final Carlos-Elisabeth farewell duet.

Otherwise, while the replacements are usually superior musically, they are not always dramatically. Regardless, whatever edition is used, something is lost. I’d rather go in the direction of the more the better. The two most practiced conductors of the opera, Claudio Abbado and Antonio Pappano, have both done various versions, though none of them with the ballet.

In terms of recordings, in 2013 DG remastered the 1985 recording of the Abbado Don Carlos. It was the Modena version en français with the six major “cuts” included as addenda. I just copied the new discs and put the addenda in their proper places. Ignoring the performance itself, this is pretty much the ideal version for me.

However, I did one better and also put together what I call “An Immortal Don Carlos” – it is a total mash-up of my favorite performances of each section. Of course, stylistically it’s a mess but what fabulous listening!

For further reading (did I seriously just say that?!), Budden The Operas of Verdi Volume 3; the ENO Guide to Don Carlos; in lieu of finding his original report, any article you can find by Andrew Porter primarily The New Yorker, January 23, 1978 or the notes in the original release of the DG/Abbado 1985 recording though he also did the notes for several other recordings; and most interesting were the notes by Christopher Wintle accompanying the EMI/Pappano/Hytner/Villazon DVD.

There are also innumerable articles in back issues of Opera News in particular William R. Braun‘s article “The Don Carlos Variations” in the January 2002 issue.