When it premiered last year, critics lauded the modernity of the Cogitore’s staging, its sensitive – even subversive – treatment of the opera’s subject matter, and, above all, Dembélé’s choreography, which fused elements of hip hop, krump, vogue, and contemporary dance into a bold reimagining of Rameau’s score. This new production, the New York Times proclaimed, presents “the true story of our times”, Rameau’s opera “swept clean and supercharged with fresh energy”.

The decision to screen the Opéra’s Les Indes galantes in New York was perhaps a testament to the international buzz created by this production, popularized on this side of the Atlantic by a widely disseminated video of one of Dembélé’s street-dance-inspired ballet sequences. The viral success of this five-minute clip catapulted Rameau’s otherwise obscure work into the public consciousness.

The screening was followed by a discussion between New York Times critic Zachary Woolfe, Cogitore himself, and the Brooklyn-based dancer Cal Hunt, who performed in (and helped choreograph) the production. “Bring it to the Met!”, gushed audience member after audience member during the ensuing Q&A.

However, performing a work like Les Indes galantes in the 21st century presents two distinct quandaries – one ethical, the other aesthetic – both of which must be reconciled for a new staging to be successful.

The ethical quandary arises, of course, from the opera’s plot, which is among the most horrendously offensive plots in the history of the artform. Rameau’s work does not follow a single storyline: it is splintered into four extended vignettes (or entrées, as Rameau termed them), each of which takes place in a different exoticized locale.

These entrées are shot through with the uncomfortable echoes of French colonialism. The first, set in the Ottoman Empire, is a love triangle between a Turkish pasha, a French girl he has enslaved, and her French fiancé. The second entrée also concerns an encounter between the colonizer and the colonized, depicting an affair between an Incan princess and a Spanish officer.However, it is the fourth entrée that today seems the most atrocious. Titled “The Savages”, it tells of a Spaniard and a Frenchman competing for the hand of a Native American girl, who rejects both in favor of another Native American. The opera ends with the European soldiers joining in a peace ceremony with the indigenous people whose land they have invaded.

This ending, in which colonizer and colonized dance together in idyllic bliss, constitutes an unconscionable case of operatic whitewashing. It presents colonial encounter as an amicable and peaceful coming together, even going so far as to imply that indigenous people were willing participants in their own colonization.

Nothing could be further from the truth. From the 16th century onwards, France had undertaken an aggressive program of colonial expansion in Asia, the Americas, and Africa. By the time Rameau’s work premiered, the French had established a far-reaching empire, built on exploitation and brutality.

Mercantile companies, in the name of trade, would bleed colonies of their natural and agricultural resources, exporting this wealth back to France to feed the growing coffers of the Bourbon Monarchy. These resources were primarily extracted through slave labor, with French ships bringing hundreds of thousands of African slaves to the Caribbean to work on lucrative French sugar plantations.

This colonial expansion was extremely bloody. The Code noir, a decree ratified under Louis XIV to regulate slavery in the French colonies, prescribed a range of horrific punishments designed to keep plantation slaves under control, including beating, branding, maiming, and execution.

In the post-screening interview, Cogitore implied that the libretto, by Louis Fuzelier, was simply a bad apple, and that Rameau’s music transcended its unsavory messages. Yet it is almost impossible to escape the specter of colonialism in French opera from this period.

Colonial expansion had produced a huge amount of wealth for the French monarchy, most of which was pumped into the elaborate rituals of court life. Opera, over which the monarchy essentially held a monopoly, formed a key part of these rituals, a means of demonstrating the wealth and power of the King while pacifying his nobles with music and spectacle.

The libretto of Les Indes galantes, rather than being a particularly distasteful anomaly, was a calculated tribute to the violent economic system which helped to pay the creators’ wages. Indeed, all of Rameau’s operas – which were among the most expensive entertainments in Europe – were contingent on wealth produced through the twin forces of slavery and colonialism.

Although Les Indes galantes may be the most overtly colonial in its subject matter, Rameau’s entire corpus is saturated with the vestiges of this horrendous history. Far from transcending the atrocities of the opera’s plot, Rameau’s score is just as complicit in the history of French colonialism as Fuzelier’s libretto.

The question remains: can we still, in good conscience, perform this work today? To mount Rameau’s opera pro forma – and without some means of addressing its disquieting colonial history – seems, to me, to be downright immoral. To present a work that glorifies colonialism in a world still reeling from the inequality, trauma, and oppression of colonial violence only perpetuates the effects of this violence. Les Indes galantes would be better confined to the dustpan of history than performed without acknowledging the harm it helped to sustain.

On the surface, Cogitore’s production seems to stage this problematic opera in a way that acknowledges and critiques its unsettling history.

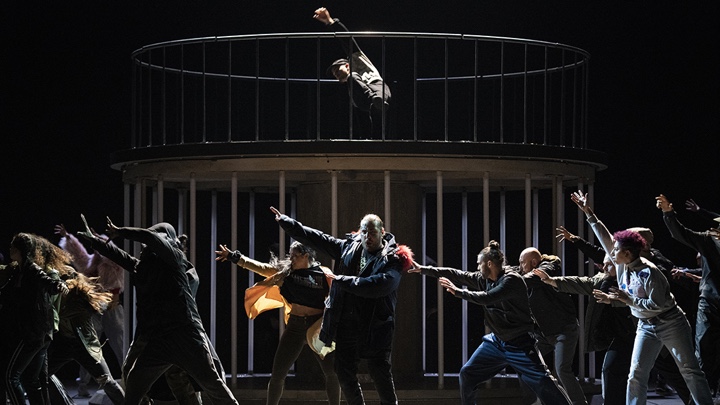

Many parts of the production are an overt commentary on racial violence. The shipwrecked sailors of the first entrée are treated as asylum seekers, draped in emergency blankets and quarantined by coastguards in hazmat suits. The fourth entrée, too, begins as a commentary on colonial violence, depicting the Native Americans imprisoned in a large cage as the colonial soldiers prance about on its roof.

Yet, large swathes of the production seem surprisingly equivocal about the opera’s racial content. Cogitore’s staging of the third entrée, despite relocating the action from a harem to a seedy red-light district, presents the opera’s plot more or less unchanged. His decision to present the opera’s prologue as an haute-couture runway show seemed like a missed opportunity for commentary on the complicity of the fashion industry in perpetuating colonial violence today. I kept waiting for a political point to emerge and it didn’t.

Most troubling of all, Cogitore ended the opera with all characters, indigenous and European, dancing together in peaceful harmony. In the post-screening interview, Cogitore claimed that this final scene was a testament to the power of music to bring people together. Yet, given the vast power imbalances on which Rameau’s opera is predicated, one might wonder how far Cogitore’s staging strays from the Enlightenment universality which afflicts the colonial narratives of the original opera.

Cogitore’s staging veers towards the subtle, the evasive, and the ambiguous. In light of the opera’s bloody history, such opacity seems to be afforded by a position of privilege.

The most politically incisive aspect of this production is found, instead, in Dembélé’s choreography. The very presence of hip-hop and krump in this production – dance styles which were developed in communities of color partially as a form of resistance against racial violence – seems like a protest against the opera’s colonial messages. These dances are positioned at points of cultural collision, emerging as acts of carnal rebellion against the colonial forces eulogized in the opera.

The dancers of the Compagnie Rualité, Dembélé’s dance troupe, performed their intricate, beautiful choreographies in defiance of baton-wielding riot police or the imposing silhouette of a colonial prison. Yet, it ultimately felt as if it was the opera itself (and the institution in which it was being performed) that these dances stood in resistance to. The choreography seemed to tear at the very fabric of Rameau’s score, undermining its aesthetic primacy, and exposing the vacuous utopianism of its libretto.

One only needs to watch the viral video of Dembélé’s choreography to see how moving this aesthetic de-centering can be.

However, as Woolfe has pointed out, there is a fine line between a colonial space being reclaimed and dancers of color being re-exoticized – the audiences for both the original production and the New York screening were overwhelmingly white, and the power dynamics of this racialized gaze are complicated and uneasy.

Returning, then, to the aesthetic quandary which arises when performing Les Indes galantes today: this lies not so much with the opera’s dramatic content, but with the genre in which it was written. Les Indes galantes comes from a long lineage of opera/ballet hybrids performed under the Ancien Régime, including the comédies-ballets of Lully and Molière and the ballets-héroïques which were an operatic staple up until the Revolution.

These hybrid forms are often senselessly long, with absurd, fragmentary plots and a stilted dramatic pace cut up by (seemingly extraneous) musical digressions. The actual plot of an entrée often occupies only about fifteen minutes of music, only to be followed by half an hour of dancing and pageantry (the third entrée of Les Indes galantes is a case in point).

These odd dramatic proportions have no doubt prevented these works from finding a place on today’s operatic stages. Yet, Cogitore’s production – which is, itself, a hybrid of many different theatrical and choreographic styles – finds grains of modernity in this antiquated genre.

It shows that there is something distinctly postmodern about the opéra-ballet, its fractured, episodic forms vibing well with the disjointed experience of life in the internet age. In an era when content is consumed in small, interchangeable chunks, brought before us in endless digital streams dictated by an algorithm, the success of Cogitore’s production suggests that the opéra-ballet may very well be the most zeitgeisty of all operatic genres.

Indeed, as I was watching Rameau’s work unfold, it occurred to me that the opéra-ballet is probably closer to a modern-day mass-media event like the Super Bowl – with its unique fusion of music, spectacle, propaganda, and athletic prowess – than it is to the operas of Verdi or Wagner.

However, a sense of contemporaneity alone is not enough. While Cogitore may have succeeded in solving the aesthetic quandaries of Les Indes galantes, until a more satisfactory approach to the (more pressing) ethical problems of this work is found, Rameau’s work is probably best left in the 18th century.