All the parts entertain: dancing, singing, acrobatics, recital of poetry, mimes of ritual, powerful singing, faintly humorous references to Ravel’s Bolero, which has the honor of having inspired choreographer and chief creator Gregory Maqoma to produce this highly physical meditation on the interaction of African, European and American societies. The work runs about an hour, the activity is sometimes dizzying, sometimes gracious, at a ritual pace, and it ends just about when the mind begins to totter from the overload of wonderful images—not a moment too late or too soon.

Only one of the piece’s many movements summons a performance of Bolero, by the way. The others are drummed (to the Bolero rhythm and to others) or sung. The music is not credited to one creator, but arose—Maqoma said during a talk-back—from the performers themselves while the piece was under construction in a South African a cappella style called Isicathamiya, arranged and put in logical form by Nhlanhla Mahlangu.

The sounds recall spirituals, folk songs of many traditions, choral religious rituals, the “click”-language of southern African tribes. The harmonies are consoling. The voices of the four singers—who also double as instrumentalists (on megaphone and harmonica, among other things)—create dignified commentary background to the highly physical dancing.

We are urged (by the ushers) to read the libretto before the performance begins. There are just three pages of it; mostly simple phrases, repeated, varied, harmonized, enacted—so don’t worry if you forget to read it.

There are only two long speeches and one of those is declaimed in English: a female dancer lures, then resists, then flirts with a male dancer, and while this erotic pas de deux takes place, she utters—to us, not to him—a chilling fable about an old woman going from house to house “teaching” women not to love their children, because they will come to some terrible death, or merely because they will leave. And while she is declaiming these horrors, she smiles and flirts and dances athletically with Doloki, the Designated Mourner, the brilliant dancer, actor, ritualist Otto Andile Nhlapo, who inhabits as many personas as a figure of mourning must.

There is a tale of sorts here, loosely derived from the novels (notably one called Cion) of Zakes Mda, a South African who dwells (and professes) in Ohio, where he has encountered the WIN people (sic), a mélange of White (Irish), Indian and Negro who have blended the haphazard remnants of their three distinct cultures. An earlier Mda novel described Doloki, a man who moved among the townships of Apartheid and post-Apartheid South Africa, taking upon himself (for payment) the duties of mourning for those slaughtered and unmourned so that their societies could learn grief and expiation. A bit like Dead Souls.

It was a surprise to Mda to learn that many societies around the world actually make use of hired mourners; South Africa not being one of them. But the era when Apartheid was overthrown, thirty years ago, proved particularly violent and disordered and in need of ways of relating to the many suddenly dead. In his novel Cion, Mda sends his Mourner to live in Ohio. There isn’t much focused narrative in the opera, and the novel may be similarly episodic.

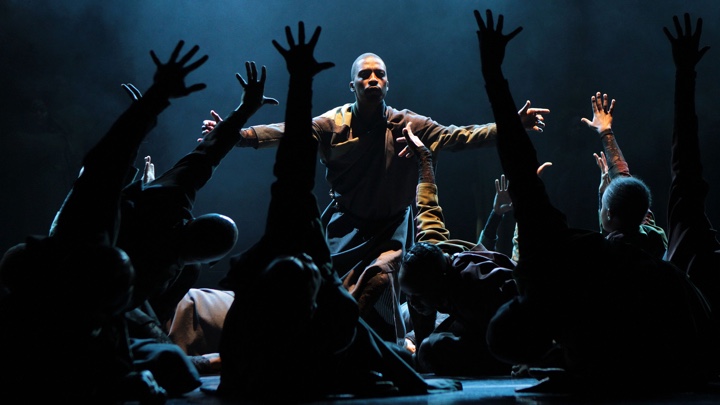

On the stage, in what appears to be a sort of cemetery (from the many crosses around the stage), a single figure crosses before us, whining and gabbling, clearly in emotional distress. The lament is for a death, but whose? We never learn. It could be for many deaths, a family’s death, even a genocide.

Maqoma claims a wish to mourn not only those who were enslaved and done to death in Africa and in the New World but also those without a grave or a memorial, the forgotten ones who died on the ships or were thrown overboard. He believes those spirits hover still, and await the mourning of those who may never have known them. That makes this, in a sense, a version of Sophocles’ Antigone.

No single person emerges to be mourned. A figure is exalted to be hailed by white gloves balled into stones. Others seem to morph in mid-dance-step into baying hounds or hyenas; they surround, assault, bring down a woman and devour her.

The religious position in a procession, the lead or follow position in a ritual, the amorous position in loving, the horror or the bloodthirst or the regret or the extinction comes suddenly abruptly upon the dancers in mid-step or collision, and the music may be subtle and appropriate or blaring and physical.

We may invent our own pictures for it: the snare drum of the armies that tore Africa apart, the ever more emphatic taps of strangely veiled and skirted processions who might be orishas of death or widows in eternal, implacable procession, a single mourner capturing the individual horrors or a crowd exploiting, reviling, dramatizing, vanishing.

It is art to express the inexpressible anguish, a gentle art but with the power of some dazzling dancing whirling in front of us to depict the terrible grieving behind it.

Photo by by Siphosihle Mkhwanazi.