Tired of all that heart tugging romance? Worn out by too much pathos, snowfall, and tears? It’s that old operatic cliché; boy meets girl, boy loses girl, girl dies. Except this time I don’t think anyone cried.

Barry Kosky, the current Chief Director of the Komische Oper Berlin, debuted this production back in February and brought it here to Los Angeles to open our season. It’s one of those moments when you realize your mother was right when she told you to be careful what you wish for. I’m not sure the LA Opera audience was quite ready for the Brechtian anti-buffet presented to them but it was mostly well thought out and a very intriguing look at an old warhorse.

As in Kosky’s silent movie Magic Flute that’s being revived for a third time here this year, this production is inspired by captured images. This time around it’s specifically tintypes. The story is moved up to the turn of the century, making Marcello a photographer instead of a painter. Enlarged tintype negatives decorate the back of the wide open stage, with no side curtains, and the Bohemian’s garret it nothing more than a small platform center with a hanging backdrop for portraits, metal stove, a small bench, and trap door for entrances.

The cast is young and not unproven which is the best of both worlds for Bohème. The quartet is led by the Rodolfo of Saimir Pirgu and Marcello of Kihun Yoon.

That happens most when he’s singing about Mimi… not to her. His phrasing alternated between the choppy and the conversational in almost equal measure, which was discouraging. Still a tenor who’s not afraid to sing softly for effect is a rare beast and should be encouraged. He did manage to rustle up a little poetry from time to time.

The group was rounded out by the Schaunard of Michael J. Hawk and the Colline of NIcholas Brownlee. Kosky was responsible for some particularly inspired stage business in the first scene including the complete elimination of the character of the landlord Benoit with each of the men taking turns with a beat up top hat and mimicking the old man’s monthly, and obviously well-rehearsed, appeal for the rent. It was a fresh bit and if you’d never seen Bohème you’d have been none the wiser of the switch. Mr. Brownlee’s bass continues to grow and impress. This was the second time I’ve enjoyed his “Vecchia zimarra” and his performance reminds you how poignant it can be with a gifted interpreter weilding a great voice.

For once Mimi’s complaint of being breathless from climbing the stairs actually carried some impact as Marina Costa-Jackson poked her head up through the trap door and promptly fainted. She’s dressed as a bit of a waif, simple plaid dress and boots (boots!) with some serious bed-head. She and Rodolfo make good use of Marcello’s camera and backdrops sitting for portraits while they sing their introductory arias. Unfortunately the effect makes it more like they are singing directly to the audience and not each other.

Costa-Jackson has a beautiful and very dark-hued voice particularly in the middle and bottom and she employs excellent diction, really digging into the words at times for dramatic effect. Above an A natural the tone tends to spread. That said, she’s the only Mimi I have ever heard who produced a very real, and almost disturbing, stage cough.

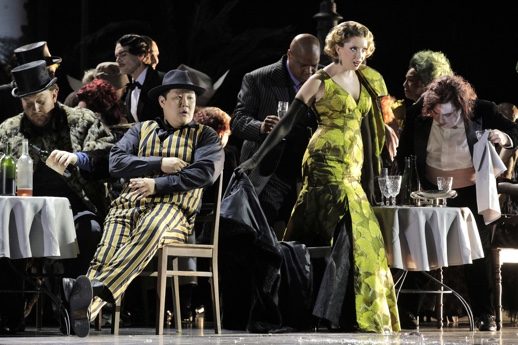

Kosky’s staging for Act II which plays through without pause (since there’s hardly a set to shift, thank you) is his chance to show off. The children all done up like little vampire pierrots and the rest of the chorus an absolute menagerie of showgirls, dandies, and macabre freaks. The Cafe Momus is a combination opium den and sideshow on an ever twirling turntable with a panoramic tintype of Paris hanging behind.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the third act of Bohème is among the most perfectly constructed and inspired pieces of musical writing for the lyric stage and here is where Mr. Kosky puts all his cards on the table. The stage was bare save for an enormous black and white tintype photo of a French street on a tarp at the rear. After an opening gag with a drunken Marcello trying to photograph some working girls in a provocative pose, all of the superfluous characters are banished to backstage.

The Customs officials, milk women, peasants, all sang their lines from the wings. Even the Customs Sergeant who directs Mimi to the tavern where Marcello is staying was heard but never appeared. Rodolfo and Mimi spend the majority of the act on opposite sides of the stage while Marcello holds down the trio dead center, making for an interesting soundscape and challenging your thoughts on the dramatic outcome.

Costa-Jackson’s “Donde lieta,” which offered an amplitude of phrasing and an indescribably delicate “Bada” bridging the two sections, would have certainly stopped the show if it hadn’t already been decided (by Mr. Kosky I’m certain) that there would be no break for applause here. When Musetta finally showed up and she and Marcello had at it Mimi and Rodolfo still remained physically distanced from each other in spite of the music and text.

After their last few insults, Marcello and Musetta suddenly collided in an apocalyptically passionate embrace, provoking absolute hilarity in the audience. Meanwhile Rodolfo and Mimi resolutely went their separate ways first with her storming off and then he resigned in the opposite direction and… black out. Not a single snowflake fell.

The last act followed hard on with some very difficult choices about having Mimi dying alone, sitting upright in a chair center stage under a harsh light, as the characters and voices around her faded into blackness. Having enjoyed (nearly) everything Mr. Kosky had done up until this point it’s something I hope he’ll re-think in a coming revival. Dramatically it’s just not satisfying or intriguing in the way his Act III was.

Ms. Bahr’s costumes, with the exception of Act II, were generally traditional and lots of plaids and striped patterns per the era. I especially enjoyed Colline’s faux fur (chinchilla?) “zimarra” which was promptly dropped through the trapdoor at the aria’s conclusion.

The sets of Rufus Didwiszus showed a great economy of design but a high level of artistic intention. The slowly turning lamp posts that subtly conjured Paris and the Momus as well as his austere Barrière d’Enfer were his triumphs. The original Lighting Design of Alessandro Carletti favored a bank of warm footlights for the actors faces and just enough light to dimly see the cavernous backstage.

The lack of a stage curtain throughout allowed us the rare privilege in the theatre to hear every note of Puccini’s score including the gorgeous postludes to the acts.

Music Director James Conlon coaxed and coerced the LA Opera Orchestra in a performance of both extraordinary discipline and rare flexibility. He was never calculated and was always striving to unite stage and pit as organically as possible. There were times where I felt I was noticing the writing for the harp and the winds for the first time. Even the horns managed a rare level of transparency.

I have to confess I was really looking forward to the musical side of things because Maestro Conlon’s recording of La Bohème (which was the soundtrack to a best forgotten film…don’t ask) is among my very favorites and worth searching out—as is this fresh take on Puccini’s reminiscence on love lost and won.

Photos: Cory Weaver