Winterreise has fortunately accumulated a varied and fascinating discography since the beginning of the recorded era. Singers that span all four categorizations of the vocal compass have committed their interpretations to the recorded medium. Some of the most distinguished on disc include those by Hans Hotter/Gerald Moore, Peter Schreier/Sviatoslav Richter, Christine Schäfer/Eric Schneider, and Christa Ludwig/James Levine.

Recently, even major artists like William Kentridge and composers like Hans Zender have lent their own brand of musical and visual experimentations with Schubert’s score. The former coupled his inky visual backdrops with Matthias Goerne‘s polychromatic interpretation to impart a more immediate and interactive vision of the work to audiences. The latter scored a somewhat controversial (but still fascinating, and at times confounding with its novel elements of orchestral embroidery) transcription for a small ensemble, last seen at Zankel Hall three autumns ago with Sir Simon Rattle and Mark Padmore.

The recording featured in today’s article represents another line of experimentation with the Winterreise poems: the original songs fitted with new texts. In this recital, the Polish dramatic bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny and his pianist Lech Napierala present the world premiere recording of Stanislaw Baranczak‘s Podróz Zimowa (Winter’s Journey), which weds the poet’s meticulously crafted poetry to the music of Franz Schubert.

The poems included in this compendium (save the sole translation of Der Lindenbaum) are original, linguistically vibrant, highly specific and exquisitely synched to Schubert’s score. Thematically, Baranczak’s texts echo those written by Müller, channeling the spirit of the original’s Byronic narrator into a spiritually wizened Romantic who expresses a world weariness about the state of our modern world.

Baranczak is a gifted and exceptionally musical lyricist. In his youth, he translated librettos of mainstream operas like those of Mozart to his own language (outside of opera, he has also rendered Polish language editions of works by writers as diverse as Shakespeare, Elizabeth Bishop, Seamus Heaney, and Ursula LeGuin).

In Podróz Zimowa, Baranczak reveals a deeply personal account of an immigrant who at once expresses fear for the state of his homeland, a simultaneous fascination and disgust with a modern society out of his pace with his own romantic sensibilities, and a concern for the precarious state of the environment.

The words in his poems are scrupulously chosen, deeply musical and rhythmically apt (terms that come to mind are the “antenna” that replaces the “weathervane” in Die Wetterfahne, or the “Krecha” that takes the place of the crow in the 15th song). The poet’s phrases spin effortlessly about Schubert’s vocal writing—the mark of a linguistic artist of the highest caliber.

Konieczny and his accompanist Napierala provide a dramatic and musically rich reading of these songs in their first incarnation on disc. Konieczny’s vibrant bass-baritone is an apt foil for Baranczak’s text. Following the libretto is a delight—there is so much clarity to Konieczny’s phrasing, so many artistically deployed inflections of voice. His play with the Polish language’s collection of consonants, vowels, and suggested sounds recreates the poet’s anguish and cynicism with the immediacy of a great lieder artist like Hans Hotter.

There is also an abundance of color in the baritone’s reading—if his triumphant Alberich at the Met embodied the full spectrum of the character’s complexities, the darker palette Konieczny employs here conveys the kind of Romantic lost in time that describe these poems’ creator. Napierala provides Konieczny with an inspired accompaniment, the sound beautifully and clearly recorded, his articulations attuned to the baritone’s colors and nuances.

Podróz Zimowa isa powerful and fascinating modern reimagining of Schubert’s great score, and I was fortunate enough to purchase a copy of the CD at the Wiener Staatsoper’s Arcadia shop. I had also met Konieczny after a performance of Dantons Tod at the Wiener Staatsoper. The interview below, very generously granted by Mr. Konieczny, provides greater detail about this special project and a more personal take from these songs’ first recorded interpreter on disc.

httpvh://youtu.be/sDAvFhD4IX0

CO: What inspired your decision to record Stanislaw Baranczak’s setting of the Winterreise poems? Fundamentally, what differentiates Podróz Zimowa from the original cycle by Wilhelm Müller?

TK: About two years ago, the director of the Chopin Institute in Warsaw, Stanislaw Leszczynski, who had wanted to organize something with me for years, contacted me with various concert ideas. Mr. Leszczynski knew that I was an actor from my first profession and that I enjoy working with words – with language – in my vocal work.

One of his concert ideas was the CD recording and concert of the new version of Schubert’s Winter Journey written by Stanislaw Baranczak. I am of Polish origin and the writer and poet Stanislaw Baranczak was a kind of icon of the underground movement in Poland during my youth, where I studied acting in Lodz. He had to immigrate to the USA for political reasons.

The Winterreise cycle he wrote is closely intertwined with his own life experiences. There are already certain parallels with Müller’s poetry in Baranczak´s text. The situation of the main actor, the narrator and at the same time the main character in Baranczak´s Podróz Zimowais, however, different from that of Müller.

The main hero with Baranczak is much older than those of Mueller. He does not mourn the own broken love for a woman, but longs for his homeland. At the same time he is however very conscious and critical of the situation in his own homeland – specifically, communist Poland.

These poems’ tone and subject are fundamentally so different from the original by Wilhelm Müller, but they still resonate so well with the music. Why do you think Schubert’s music is such a universal canvas, even for poems with themes so modern and far removed from the narrator of the original material?

The idea of setting new lyrics to existing music is not new. It is actually much older than the composer’s setting of the text. In the Middle Ages, this was a very popular method of writing vocal music. Baranczak was also a prolific translator. He translated almost all of Shakespeare’s plays into Polish. He also translated two Italian operas into Polish.

Even in my youth I sang one of these operas in Polish as Figaro in The Marriage of Figaro by Mozart. Baranczak had a very good ear for music, was very intelligent and had a very good sense of humour. He was very taken with a recording of Hans Hotter’s Winterreise. I think that Baranczak loved Schubert’s Winterreise and deemed it incredibly important, so much that he identified himself in this work of art.

Baranczak’s poems tell us the story of a Polish immigrant who seems to have been embittered by his exile. Can you tell us how these poems speak to you as a Polish individual and artist? Are there any personal or historical experiences from your homeland that help you resonate more deeply with Baranczak’s experiences?

I was and still am very proud of my homeland (Poland), which rejected communism without bloodshed 30 years ago. When Baranczak wrote Podróz Zimowa, that peaceful outcome was not so self-evident. People in Poland, like Baranczak, were completely isolated from their own countrymen and banished out of their homeland for political reasons. These people were not allowed to return to Poland at all—they became refugees.

After Poland experienced 30 years of pride and optimism, the insidious, dictatorial spectre of the PiS (Prawo i Sprawiedliwo?? or Law and Justice)Party and that morally questionable Zwerg [literally a dwarf, but think of a slimy, sniveling character like Mime – CO] Jaroslaw Kaczynski unfortunately returned to power in my homeland. So unfortunately I have this great fear for democracy and freedom in Poland again.

The great poems of Stanislaw Baranczak are once again gaining in importance nowadays. Additionally, apart from their political content, they are also commentaries about the ecological condition of man and our planet Earth. Just as at the time when Schubert first presented his Winterreise, Baranczak’s new cycle of poems resonates with themes that are so pertinent today that they give one a cold shiver about our modern condition.

Can you tell me more about Polish as a language of musical expression? Baranczak of course very judiciously set words that conveyed images and meaning to the music, but I am more curious about the language itself. For example: how does the Polish language’s consonants and vowels work to help convey a certain idea?

When translating librettos and poems, Baranczak worked very hard to imitate the sounds of the text written in Polish to emulate the foreign original. These poems display great artistry and versatility of this writer’s verbal workshop. This, of course, makes performance practice much easier, even though the Polish language is not easy to sing.

Rather Podróz Zimowa exceptionally and musically written phrases make it a lot easier. There are very few closed vowels in Polish, and that in part is for the language’s culture of song in performance practice. For me, this Winterreiseis a return to my native language, to my first profession as an actor. It is a beautiful, but not an easy journey.

With this new text, did you and Lech Napiera?a make any changes (for vocal line or the piano score) to the rhythms or the dynamics of Schubert’s score to accommodate the themes of Baranczak’s poetry?

No. We haven’t changed anything. Baranczak crafted his poems and sounds to the notes scrupulously. All Polish lyrics fit exactly to the music. There may be slight differences in articulation sometimes, but we didn’t have to change anything. Baranczak was really a master!

Let us talk about the poetry in this recording. Are there any fundamental differences between Baranczak’s translation of Der Lindenbaum compared with the original? Can you name any specific changes in the coloration of the words or the music?

“Der Lindenbaum”is the only translation in the whole cycle. So one translation and 23 freely written poems. The spirit in “Der Lindenbaum” is exactly the same as in Müller. One would think that Baranczak first translated this song, that he perhaps wanted to translate the cycle further, but then decided on free poetry. But we don’t know exactly why only “Der Lindenbaum” was translated. Unfortunately, Baranczak is dead. So you can no longer ask him personally.

You mentioned that XV (“Krähe”) and XXIV (“Leiermann”) are your favorites in this cycle. What about Baranczak’s “Krecha” makes it so suited to the dark nature of the original song?“Krecha” is a prank in Polish. The narrative role of the crow, an animal just waiting to scavenge the remains of the host after his death, is conferred onto the “Krecha“ in Baranczak’s poem. The prank in the poet’s mind is represented by white traces of aircraft exhaust that mercilessly pollutes the original paradise, personified here by a pristine, blue sky.

Here we see an example of Baranczak employing his dark humor, which cleverly unites his carefully written text and sounds with subjects, qualities and worlds that are so different from Schubert’s great Die Krähe.

The “Leiermann” tells directly about Baranczak, about how one ages and thereby this last Lied in the Podróz Zimowa is incredibly personal and touching.

Why are these my favourite songs/poems? I think, because they are miniature representations (microcosms) of the poet. Because they are so delicate and pointed. Because they touch me.

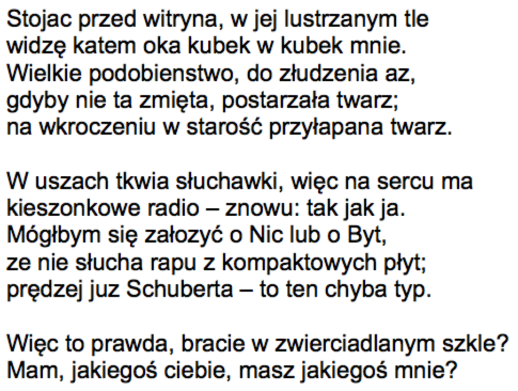

I have one final question about the Leiermann piece in this recording. At the end, Baranczak portrays the narrator seeing his own reflection on the mirror while listening to music on a Walkman. Very different of course from Schubert’s original, where the narrator encounters an old man playing a hurdy-gurdy (Drehleier). Can you tell us more about this poem, as I find it so fascinating?The solitary wanderer of Müller’s poems is, so to speak, also a reflection of the narrator. At the same time, he wanders about like a spirit and is a passive actor. Just like Baranczk’s mirror image, the loner remains distant from what he sees but is somehow intrigued as well. The loner reflects the artist Schubert in the same way as the mirror image reflects the poet Baranczak at dusk in the shop display case. Just as with Müller, the mirror image is surprisingly old.

Standing by a window, suddenly I see

In its dull reflection: someone just like me!

Just the spitting image, no real difference,

Were it not that wrinkled, wizened countenance,

Caught upon the threshold of grey eminence.Wired-up tiny earphones, so he’s got, I see,

Music in his pocket—just the same as me.

I could place a wager with no strings or traps,

That his CD’s playing anything but rap;

Schubert’s much more likely, just that kind of chap.So it’s true, my brother, truly we can see:

I have got a you here, and you’ve got a me.

Thank you so much for talking about this very special project. I have been a huge admirer of your work in many of my favorite operas. Apart from the great roles that the public has already seen (Alberich, Wotan, Wozzeck, Telramund, Dutchman), are there any new characters we should anticipate for the future? Are there any new operas and roles that you are excited about?

I have already sung with great success the part of Danton in Danton’s Deathby Gottfried von Einem at the Vienna State Opera. Currently, I am preparing the role of Barak in Die Frau ohne Schattenat the Vienna State Opera with Christian Thielemannas conductor.

In September, together with my pianist Lech Napierala, we will record the original version of Schubert’s Winter Journeyin Poland. I am very, very excited! A CD recording of 6 song cycles by a Polish composer Romuald Twardowski follows. This will take place in September 2019. There are a lot of plans and ideas and many great roles next season.

Most of the time, as always, I get as excited as a child whenever I sing Wotan, which I will sing at the Teatro Real in Madrid and later at the Vienna State Opera.

The coming season at the Vienna State Opera will be very, very exciting. My roles include: Barak, Peter in Die Weiden (an opera by Jorg Widmann), Wotan/Wanderer, Mandryka, Cardillac (a Hindemith opera), Pizarro.

Then there is the Polish opera Halka at the Theater an der Wien in December 2019, where I will sing the evil hero Janusz, and Bayreuth again at the end of the next season.

Thank you again for your time. We look forward to seeing your work again in the future.

Thank you very much!

httpvh://youtu.be/jQGE2MUc90Y

Tomasz Konieczny and Lech Napierala’s recording of Podróz Zimowa can be purchased from amazon.com. The translations aren’t readily available online, so this physical recital disc is really the only product that features descriptions and translations of the work to German and English. It’s an exceptional collection.