Four years ago, Dolly Parton manifested a shabby but functional turntable on my street corner, just in time for Partonnukah, the holiday we select few celebrate around that clump of other holidays you hear so much about in the dark part of the year when the only discernible options are listening to “Jolene” on repeat or setting off on a whaling ship.

Vinyl hadn’t been an obsession in a decade—during which I’d had no working player— and it didn’t reëmerge as one right away, but at one point I spent a couple of months on the dole and dollar record shopping had a number of obvious virtues as a pastime.

It was cheap and low commitment. You forked over a ten and got home with an armful, and some of them were scratched or awful and you gave them to somewhere else that would toss them or sell them to some other neurotic.

You do have to mind how they accumulate or you wall yourself in, as many of my friends have found out over a lifetime, with nary an Egyptian warrior to speed the hours ‘til suffocation.

Whatever lousy things I may have to say about the Bay Area—trust me, you don’t have time—I have to concede that it’s something of a vinyl-lover’s paradise right now.

The mystery and dreams you find in a junkyard, as they say. A recent trip netted me half a dozen discs including Steber’s account of Les Nuits d’Été, which I discovered Freshman year of college and have loved ever since. (Tell me about her French and I’ll show you the back of my hand.)

The others were forgettable but the lot of them cost me about as much as some novelty frappe so who cares, Edith?

By the same token, it’s easy to stumble onto things you’d never thought about but might love, if you can browse, but I mean actually browse physical objects.

I’ve brought home The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi starring Lili Chookasian, a Graziella Sciutti recital, and Simoneau’s Duparc songs, with varying degrees of payoff. At a buck a throw, it’s hard to care if one out of three is a bomb. (Thank you, Madame Chookasian, but we’ve decided to go another way.)

An early Dutch recording of From the House of the Dead. Cleo Laine’s Pierrot Lunaire and Hildegard Behrens singing Berlioz and I’m not kidding about either. The Cloe Elmo recital that comes as side 4 of some other goddamn thing.

After years of optimistically buying mid-century recordings of early music thinking they’d smell less of an archive than modern ones and finding them instead, to a one, merely loud and clumsy, I stumbled just this week on Hugues Cuénod’s disc of troubador songs—subtle and warm.

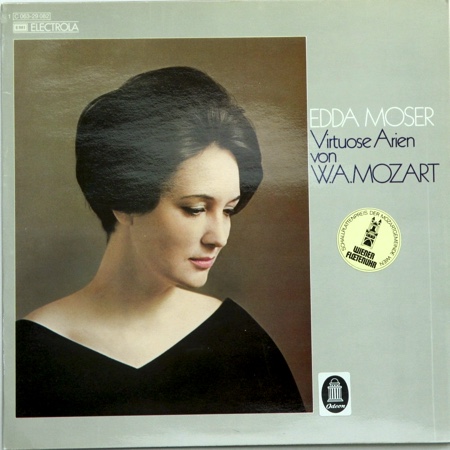

Not far removed, recall the thrill of having a holy grail, suffering in search of it, and eventually finding it. In 1992, KMFA in Austin played Edda Moser’s account of “Der Hölle Rache.”

Friends told me it was off a Mozart album that was unusually difficult to find, so I looked and looked—at my friend’s store in a garage in his backyard, at the place everyone swore by in Princeton, at Academy once the fates led me there; once a copy was even snapped up right in front of me.

All this aside, though, I’m enjoying music more in this rededicated vinyl era than I had been for a long time, the instant gratification of Spotify notwithstanding or indeed in contraposition.

I won’t go so far as to wax ecstatic about the warmth of the medium like some undergrad with a topiary beard, but I can’t deny that it may be in part because the imperfections of the medium feel akin to the imperfections, say, that make live recordings so much better than studio ones.

In larger part, though, it’s because flipping through bins and finding something and bringing it home and putting it on is, historically, for me, part of the experience of listening to music outside of live performance, and I miss it.

There was something about buying a recording of a singer you loved or a singer you were curious about that made you feel a connection to that singer and that music, amplified the fulfillment of musical discovery.

And, corny as it is, the record shelf, when it has solid objects on it turns into a kind of musical biography. I couldn’t pass by a copy of Switched on Bach, deadname on the cover and all, that we used to listen to in the car on cassette on the way to school.

The Elektra we put on one Halloween in college to scare away children with Jean Madeira’s cackling. Price’s Blue Album that I spontaneously bought on CD for a friend and mentor now passed on when he took me to the Met for a Turandot I couldn’t admit was terrible.

Turandot itself, with Nilsson and Corelli, which I got on LPs at the public library and put on cassette for the boy I fell melodramatically in love with at seventeen, and the only recording of The Mother of Us All. which we listened to at Glimmerglass the summer I was falling melodramatically in love at twenty-four.

The point of this, insofar as there is one, is to say: it isn’t too late. Old media aren’t gone, and there’s no shame in being an eccentric. Go forth, young queens, if we’re not all crones here, and ignoring the faddish taint of it all, drag home a phonograph. You’ll be the richer for it. But if you spot a copy of Steber at the Baths, watch your back is all I’m saying.

The origin story of the zine, the blog, the Weltanschauung are gospel around here and it didn’t seem like my place to retell it. I’m never in the right place at the right time and I never know what the next big thing is, and back in the days when parterre box was on paper and you simply had to be someone who knew about the best things to subscribe to it, I wasn’t that kind.

I do remember the roots of opera queendom in what was quaintly termed cyberspace in all their glory and all their tedium: back in the days of rec.music.opera I once even had a flame war with our own James Jorden over the authenticity of the name Boleslao Lazinski.

There was an education to be had even then, but it wasn’t until Parterre that there was, I would say, a real community.

I have often said that James invented the way modern opera queens talk: to the art of reviewing he added a frankness that breathes life into what otherwise might be a catalogue of high notes, that indispensable dash of vulgarity that from time to time is needed, shameless love of the art, and above all else, wit.

Comments