“Voi manderete tutto alla malora! Vergogna!”

Lately it seemed all the best digs could be found in The Metro Times. However, Friday afternoon, later than usual, Evan Ingersoll received an ecstatic, emoticon-filled text from his compadre, Jesús Halévy, encouraging him to pick up The Village Void. Evan clicked over to the his favorite music critic’s weekly column, “Slings and Arias.”

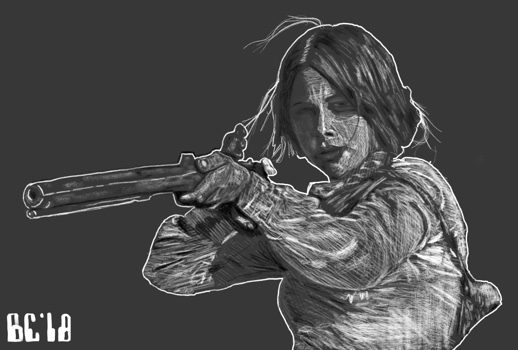

Redelivered BASTA Shoots Up

“La Fanciulla del West”

By Waspington Rhubarb

With its lush harmonies, rich textures, and possible nods to Wagner and Debussy, Puccini’s “La Fanciulla del West” is in many ways the most innovative of the composer’s later works. Arturo Toscanini, conducting the premiere in 1910, famously referred to it as a “symphonic tone poem.”

Toscanini knew then that the opera’s greatest asset was identical to what conservative listeners might have once considered a flaw: it doesn’t lean too heavily on individual set pieces and arias, instead allowing its onstage action to unfold organically with Puccini’s vivid orchestrations.

But going solely off the newly revived Big Apple Singing Theater Association’s latest production, which opened last Thursday at the Mariachi Playhouse for a four-day run, one would think the masterwork not only free of arias and set pieces, but entirely free of music as well, so indecent and excruciating were the noxious sounds emanating from the pit.

And on the off chance that one is mercifully impaired enough to tune out the din, there are a hundred other horrors to be encountered in this sideshow. There is, for instance, the stabbing anguish of realizing that “Fanciulla” is lost to you forever, because you’ll never be able to shake its leading players’ performances from your memory.

The decision to revive BASTA last year was well-intentioned enough. In the 70 years since its inception, the company had served a welcome alternative to its bigger, richer sister in the city, the Algonquin Opera. Indeed, for those who had tired of the orthodox stagings at Lincoln Center, BASTA was at one time a breath of fresh air: a vehicle for new faces and fresh works, an incubator for fledgling directors who in just a few years’ time would fetch A-list commissions from A-level houses.

Times have changed since 2015, however, when BASTA filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy following years of floundering ticket sales, the incarcerations of multiple board members, and a poorly received production of Thomas Adès’ “Michael and Macauley.” Ten months ago, emergency nonprofit Redelivery Ltd. stepped in to save the so-called “Plebes’ Opera.” The one stipulation? That “Fanciulla del West” be the first song of the phoenix, newly emerged from the ashes of financial strife.

There is no good reason to believe that BASTA is fully out of the woods. The first production of its self-proclaimed “Redelivery” season feels dead on arrival, its elements failing to gel as a cohesive whole and its individual parts proving bleakly incapable of capturing any of the intrepid spirit of the golden west.

Part of the problem lies with the new production’s central conceit: this “Fanciulla” offers a facsimile revival of the company’s first-ever production, and draws on archival photos to recreate the original 1945 sets, costumes, machinery (in the form of a villainous vintage Fresnel Lens spotlight that makes a ghoulish spectacle of a Pony Express rider and a burnt offering of pretty much every unsuspecting female on stage), and props for the inaugural 2018 show. Longtime director and BASTA general manager Joey Piccatahas resurfaced from his own legal battles to wagon a young cast of unknowns to the foot of the Cloudy Mountains mining camp where much of the action takes place.

In this staging, Piccata attempts to honor Puccini’s original source material, a David Belasco melodrama made popular on Broadway in 1905, as well as the theatrical sensibilities of 1945. Adding to the confusion, the resulting “look” of the show takes its cues from both periods and then spikes the proceedings with an incongruous 20- to 21st-century naturalism that renders the finished product looking like an outtake from “Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey.” It’s as though a couple of mall rats had donned post-war nylon western-wear from a Cato Corporation and stumbled into a silent Pathé Frères newsreel.

And I suppose we’ll never know if it was budgetary setbacks, blindness to detail, or simply a tin ear for common sense that led Piccata and costumer Eugenie Puant to outfit the players in flip-flops, scrunchies, and, in one particularly degrading case in act three, a pair of neon pink, calf high, Tony Lama riding Wellingtons.

Which brings us to the larger issue of the evening, the production’s casting choices. In “Fanciulla,” plot revolves around two points: the lived experience of the miners, and the white hot chemistry of a feisty, gun-slinging (but ultimately caring) saloon owner named Minnie and a beddable bandit named Dick Johnson.

BASTA’s leads missed the memo on both. My powers of recall prove at times unreliable. But I believe I can ethically report that outside of Williamsburg, I have yet to chance upon such a kitschy embarrassment of Bonanza extras in one place as I did during the opening-night barroom choruses of this production.

These miners out west, who are supposed to evoke the era’s deeply-felt longing for home—the opera’s emotional nucleus—appeared to know little about longing, or depth. Or, if they did know something about either, the construction of their home would likely raise flags for any building inspector. Over the card table or in the forest, their crew looked restless and unfocused. At one point I blinked in horror as a lone chorus member preoccupied himself with a scab for a full 15 minutes upstage.

Supporting roles fared only marginally better. As impetuous sheriff Jack Rance, baritone Nico Hammerstein (“IV,” the program informs us) did his best with a revolver and ankle holster that kept slipping down his leg like an errant garter belt. Rather than let it sit on the floor, Hammerstein interrupted his big act one aria on opening night with a tug of war with the leather scrap that caused him to trip and accomplish close to a full somersault parkour into a barstool.

Puccini’s treatment of Native Americans in this work has always been the object of worried scrutiny, with many companies doing their best to endow the Indian characters Wowkle and Billy Jackrabbit with enough pathos to help contemporary audiences stomach the caricatures.

Choreographer Vanessa Spoleto has truly outdone herself here: her whooping, stomping, palm-to-mouth Indian dance for mezzo-soprano Sassy Burnheart and bass Pumpkin Zinnewax, two character actors last seen in the Algonquin Opera’s staging of “Ariadne auf Naxos” last season, was so brazenly offensive and anarchic, it seemed tailor-made for some museum exhibit on the history of American prejudice, or a Klan rally.

Playing Minnie, Tallahassee-raised soprano Martina Tebalding did that thing she’s become known for where she yodels like a lost Alpine while lurching into her head voice. Dear reader, her sound has admittedly never been a favorite of this reviewer’s; even through the scrim of my personal distaste, however, I truthfully could make out a single intelligible syllable of her Italian. Her exchanges with Dick Johnson, in which she softens to his advances, was delivered with the kind of mush-mouthed, slack-tongued diction (and only a shred of the pathos) one hears from a recent stroke victim who’s just smelled toast. Only a morbid lack of self-preservation could account for her perverse approach to handling a gun in such a manner that it would become painfully ambiguous to us which “Dick” she was most interested in.

The howling tenor of Bruce DaBruce made for interesting listening, if by “interesting” one means splitting and “listening” one means migraine. His “Ch’ella mi creda” aria, in which he movingly pleads with the miners not to report his coming demise, is supposed to be a showstopper; DaBruce sang through a dismal series of tics, belches, and cracks. There is no reason to believe DaBruce should be a star. But the notion that there are agents out there who would force DaBruce upon us worries me, in much the same way disaster porn, makeup on infants, and my mother’s mouth noises worry me.

One would wish the orchestra might drown out the leads. But under the baton of new BASTA maestro Robert Richard Spandez, a onetime regular at Detroit Light Opera, I must say an orchestra has frankly never sounded more subdued. Spandez is slated tox lead the BASTA crew again in just a few months for the company’s second western-themed opera of the season, Zack Wedgie’s Bison Don’t Cry. Bison might not, but his sad-faced musicians certainly will, if he doesn’t bring his score to the next production.

Spurning the Jack Rance’s advances in the first act, Minnie begs him to stop: “Rance, basta! M’offendete!” she sings. Would that the redelivered opera company learn to quit when it’s behind: that way, Minnie would be the only one left having to say the company’s name.

Illustration by Ben A. Cohen