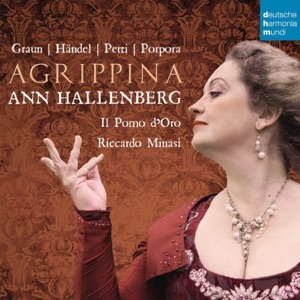

Fans of divas who sing 19th and 20th century opera may find themselves searching in vain for CDs to buy with this season’s gift cards, since their idols so rarely put out solo recitals these days. Yes, Olga Peretyatko delivered Rossini to mixed responses, and Anna Netrebko’s verismo collection will burst forth sometime next year. But for those who also enjoy pre-bel canto arias a whole slew of recent releases has already arrived ranging from Dorothea Röschmann’s unnecessary Mozart recital to one of the finest CDs of this young century by Ann Hallenberg.

This disc, Agrippina, instantly became an indispensable recital CD for anyone interested in great singing. The great Swedish mezzo’s North American appearances have been shockingly few; however, many of us have come to know and to love her via her extensive discography. For example, The Hidden Handel from several years ago

was a knockout, but Agrippina is even better!

As Hallenberg’s own essay with the CD explains, there were at least three historical personages known as Agrippina, all depicted in 17th and 18th century operas. Accompanied by Riccardo Minasi and Il Pomo d’Oro, she performs eleven arias for those notorious women spanning Giovanni Legrenzi’s 1676 Germanico sul Regno to Carl Heinrich Graun’s Brittanico from 1751. The most famous Agrippina opera is, of course, Handel’s 1709 masterpiece, and Hallenberg has recently been a superb interpreter of its title role.

Those who have suggested that nothing on the CD can compare with Handel’s music are ignoring some enticing delicacies like the rollicking “Date all’armi” from Giacomo Perti’s Nerone fatto Cesare or a sublime slice of Telemann’s Germanicus—could this derided composer’s many operas hold more gems like this?Hallenberg has never been better—her rich, nimble mezzo brilliant and free on top, her jaw-dropping coloratura a miracle of precision and panache.She is in similarly heroic form on a second new recital, Arias for Luigi Marchesi, but it’s less essential due to the album’s oddly unfulfilling journey. With surprising regularity new disks appear featuring music written for famous castrati. While most often they feature a countertenor, mezzos still occasionally get a chance at bat: Vivica Genaux’s Arias for Farinelli was an early hit

.

Marchesi (1754-1829) reigned as one of the great singers of the last quarter of the 18th century, but he doesn’t appear to have inspired his collaborators who include Domenico Cimarosa and Johann Simon Mayr. Conductor Stefano Aresi has assembled a cluster of prosaic arias apparently chosen primarily because Marchesi’s own ornaments exist. As those decorations tend to emphasize empty virtuosity, the disk threatens to become an academic exercise with thirteen minutes devoted to two renditions of a bland Cherubini aria featuring slightly different Marchesi variations.

Aresi’s scrawny-sounding period-ensemble Stile Galante lets down our intrepid diva who bravely soldiers on through swathes of wickedly demanding, not very memorable music. For those of us who crave the chance to hear Hallenberg live, she’ll finally make her much-belated New York City debut with the Venice Baroque Orchestra in early 2017 singing Vagaus in Vivaldi’s Juditha Triumphans!

Devoted to not one but three singers of the past, Sabine Devieilhe’s newest CD Mozart: The Weber Sisters with Raphaël Pichon and Pygmalion also suffers from a heavy-handed program that investigates the three sisters’s influence on Mozart.

The meat of the program is four brilliant concert arias written for Aloysia which Devieilhe dispatches with easy agility and radiant high notes, but one wants greater fervor in “Popoli di Tessaglia.” She musters surprising bite for the Queen of the Night’s “Der Hölle Rache” (premiered by Aloysia’s sister Josepha), but her glowing “Et incarnatus est” lacks real trills. Rather than the dull orchestral fragments and an affected, breathless “Ah, vous dirai-je, maman,” we might have instead enjoyed Devieilhe in another concert aria or two.

Less than an hour long, Röschmann’s new Mozart collectionGerman soprano Christiane Karg has garnered a lot of attention lately in the lighter Mozart roles in which Röschmann once excelled. The abruptly titled Scene! finds Karg in way over her head for five dramatic showpieces that include another heavenly Mozart concert aria, “Ch’io mi scordi di te,” as well as Beethoven’s ferociously demanding “Ah, perfido!” Accompanied by Arcangelo conducted by Jonathan Cohen, she sounds thin and plain squeezing out high notes and charging through inelegant passagework. Little on this disappointing disk explains why Karg has already recorded at least four other solo CDs.

Previously unknown to me, another German soprano Charlotte Schäfer has inexplicably released Sol Nascente, which features an enticing selection of arias from early Mozart operas and rarities by Tommaso Traetta and Niccolò Jommelli. Unfortunately it unleashes some of the worst singing I’ve ever heard on disk. With an empty, girlish voice and an inadequate technique, she tackles some of the most demanding early classical arias with excruciating results. You’ve been warned!

This collection focuses on music written in Italy during the early 1700s, and, like her previous recordings, exhibits a frustrating marriage of a stunning bravura technique to a bland disengagement from the text’s meaning. In fiery or melting arias from the early oratorios, she might as well be singing solfège. Her rapid-fire coloratura astounds in its speed and exactitude while the tone remains white and sour.

While a more penetrating interpretation than Lezhneva’s, her “Pensieri” lacks the blazing insight of Hallenberg’s. For the moment, Staskiewicz is also a dazzler, tossing off volleys of dizzying coloratura in arias by Giovanni Pergolesi and Nicola Porpora with entrancing flair, though she can also infuse Vivaldi’s “Sovvente il sole” with moving pathos.

For the fourth and bestCharming, bright-voiced Portuguese soprano Ana Quintans dives into fetching excerpts from five obscure operas by a composer best known for an adagio he didn’t even write! If these arias don’t reveal an undiscovered operatic master, they afford us a chance to revel in Quintans’ piquant and stylish way with this music, particularly the stirring “Vien con nuova orribil guerra” from La Statira in which she duels brilliantly with a martial trumpet. So often the instrumental pieces on recital disks can feel like filler, but Albinoni’s here consistently beguile.

Arias from Alessandro Scarlatti’s enormous and sadly ignored vocal oeuvre are featured on Con eco d’amore, The English Concert’s unusually interesting collection featuring soprano Elizabeth Watts and conducted by Laurence Cummings.

A perfect adjunct to Max Emanual Cencic’s recent Arie Napoletane which also featured Scarlatti, Watts’s spirited if sometimes unlovely singing encourages the notion that Scarlatti who wrote over 60 operas and hundreds of cantatas could be the next logical candidate for a wide-ranging revival. One highlight is the haunting “Ombre opache” from the cantata “Correa nel seno amato,” while three arias belong to a rarity familiar to Joan Sutherland fans Il Mitridate Eupatore which the Australian diva performed just before her rise to international fame. Watts opens the disk with a finely fiery “Figlio, tiranno” from La Griselda, Scarlatti’s final and best-known opera, one in which Mirella Freni appeared several times early in her career and one once available on a fine recording by René Jacobs.

One of Jacobs’s favorite singers, Sunhae Im, has recorded has recorded four cantatas about the legendary musician Orpheus including one by Scarlatti.

No one will claim these are important pieces but it is enjoyable to hear how differently these Italian and French masters depicted Orphée/Orfeo. While the Scarlatti and Pergolesi performances are pleasant enough, she sounds completely at sea in the Rameau and Louis-Nicolas Clérambault. Disturbing recent broadcasts featuring Im suggested she was going through an alarming rough patch, but she’s secure enough here vocally though little convinces me she merits her international prominence. Her piping soprano is shallow in the middle and squeaky on top; it serves well enough for Papagena which she recorded for Jacobs but it’s wearying for a full-length solo program.

Four mezzo candidates—Genaux, Sonia Prina, Mary-Ellen Nesi and Romina Basso—vie for the title of Baroque Diva on the eponymously namedThe fascinating repertoire—previously unrecorded arias by Porta, Sarri, Vinci and Hasse among others—is the disc’s biggest attraction as none of the four are at their best and seem merely pretenders compared to Hallenberg. Genaux contributes some of her strongest recent singing particularly in making sense of the insanely difficult aria “Amor, dover, rispetto” from Veracini’s Adriano in Siria. She wisely avoids anything high in her three arias, but as always I rarely derive much pleasure from her unsteady, wiry voice.

Nor do Prina’s increasingly leathery, effortful performances give much joy these days. Despite some strain, Nesi always gives her all, and her lean mezzo excels in Clitamnestre’s furious outburst from Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide. Basso remains an opulently mannered singer, but her deeply felt eloquence shines through in “Vedrò con mio diletto” from Vivaldi’s Il Giustino.

My extended compendium here doesn’t even begin to cover all the recent releases, which include an intense if exhausting two-disc survey by the Argentinian soprano Mariana Flores of the many operas by 17th century Venetian master Francesco Cavalli.

But if one more “O mio babbino caro” will drive you batty, you might want to dive instead into one of these treks off the beaten track. Of those, Agrippina in particular, should prove a compulsively listenable introduction to Roman royalty behaving badly.