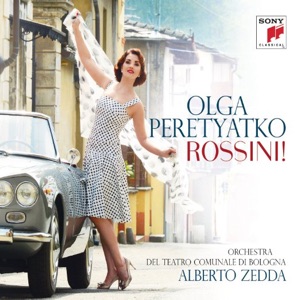

For her third solo recording

Olga Peretyatko summons the two men who launched her career less than a decade ago: the first one is conductor Alberto Zedda, who discovered the then-unknown Russian soprano in an audition in Germany; and the second one is Gioacchino Rossini himself. Indeed, Zedda, artistic director of the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro, immediately cast her as Desdemona in a production of Otello featuring big names such as Juan Diego Flórez and Gregory Kunde, and a star was born, who very soon graced the stages of the most prominent opera companies firmly ensconcing herself among the A-listers. Her beauty, her fashion sense as well her high-profile marriage with another fast rising talent, former enfant prodige conductor Michele Mariotti, certainly did not hinder her career; neither did an exclusive recording contract with Sony.

Rossini!, her latest CD, includes some of the most demanding music the Swan of Pesaro wrote for a soprano. Peretyako wisely avoids for the most part the heavy roles Rossini composed for his wife Isabella Colbran, which tend to lie in a low tessitura, and focuses on on the higher-lying parts he wrote for full-fledged sopranos such as Laure Cinti (Folleville’s aria in Il viaggio a Reims) Francesca Maffei Festa (Fiorilla in Il turco in Italia), Elisabetta Manfredini (Amenaide in Tancredi) and Caterina Liparini (the protagonist of Matilde di Shabran.) The only Colbran aria she attempts is “Bel raggio lusinghier,” which, divorced from its context, has since the mid-nineteenth century become a vehicle for nightingales, even after the opera itself had vanished from the repertoire.

It includes a single Giuditta Pasta aria, the “Improvviso” from Il viaggio a Reims, which however does not represent the type of more dramatic music for which the then-young illustrious primadonna would soon become famous. “Una voce poco fa” is sung in the traditional soprano key of F major, half a step higher than the original version: the ornamentation is full of upwards variations that do not disfigure the melodic contour of the aria, as it often happens when coloratura sopranos misappropriate it.

A clear pattern emerges from even the most casual first listening of this recording: everything Ms. Peretyatko does, she does best when singing at soft dynamics, and in any case not louder than a mezzoforte. Above that, her voice sounds driven, somewhat thick, and acquires a hard edge throughout her remarkable range, particularly in the upper-middle and high registers. Listening very carefully, it is already possible to hear the pressure causing a beat, which, at the moment light and not intrusive, hints at future possible trouble.

A sign of technical unevenness is a certain inconsistency and unpredictability: one particular difficult high note may turn out perfectly acceptable, even round, and then a few measures later it will become wiry, with a slight neighing quality. For example, in the Semiramide cavatina, the high C# in the cadenza is quite a nice sound, but the same note in the puntatura at the beginning of the daccapo of “Dolce pensiero” is forced. In general what I find missing in her singing is a lack of floating, something of vital importance in an aria such as Corinna’s Improvviso, which, relying on nothing but an ethereal harp accompaniment, in Ms. Peretyatko’s rendition does not quite convey the appropriate sense of repose and Apollonian serenity.

Likewise, her florid work, accurate and even meticulous if produced piano, tends to become chopped and imprecise whenever she turns up the volume. Rossini however requires both types of agility, di grazia as well as di forza, often in the same aria, side by side. Let us consider one particular phrase once again in “Bel raggio lusinghier”, “ogni mio duol sparì”: the two ascending roulades, both going from a E 4 up to A 5 on “sparì” and the article “del” call for a more forceful coloratura, whereas—to achieve a musically appealing symmetry—the two sextuplets (“sparì” and “pensier”) are better sung gracefully.The soprano does all this but, while the sextuplets are precise and flowing, the roulades turn out somewhat smudged and clumsy. Probably aware of such a limitation, she frequently performs them soft even when, as in the desperate cabaletta of “Squallida veste bruna” they should be more aggressive and incisive. In conclusion she is too guarded and circumspect in her florid work, which is not delivered with the nonchalant effortlessness of a true virtuosa

The Rossini Renaissance of the late 1960s could not have happened without Zedda; while nobody would deny his crucial contribution as a musicologist, his conducting has often been the target of significant criticism. I have personally always admired his approach to bel canto. Now eighty-seven years old, Maestro Yoda, as he is affectionately called in the operatic world, shows once more how Rossini should be conducted: his instrumental texture is unfailingly transparent, translucent, luminous and laced with finesses, his rhythmic play is energising.

The introduction to Rosina’s aria is an example of the filigree work he creates with the Orchestra of the Teatro Comunale of Bologna, which possesses the most intimate familiarity with Rossini in the world. However, no matter how pivotal the conductor’s work may may be, a soprano singing seven big arias with a relentless drive, scarce characterisation and hammering away at the upper register is ultimately fatiguing to hear.