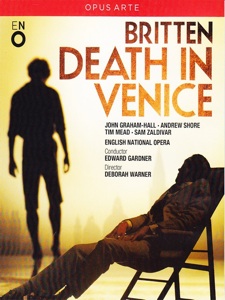

Benjamin Britten’s final opera Death in Venice, based on Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella, is given a lush and quite beautiful production from stage director Deborah Warner for the English National Opera in this Opus Arte DVD

filmed in 2013. Featuring almost magical settings by Tom Pye, luminous, wind-blown fabrics and water projections lit by the heat and sun effects of the lighting by Jean Kalman, the production gives an almost perfect frame for Britten’s tale. But for all the beauty and appropriateness of the frame, the picture itself is, for this reviewer, a deeply flawed masterpiece.

The story of the blocked writer Aschenbach’s journey to Venice (La Serenissima) in hopes of rekindling his inspiration becomes a study of obsession as the writer finds himself desperately drawn to Tadzio, the young and beautiful “Polish boy” vacationing with his family at the same hotel.

The homoerotic element of this obsession is noted but not dwelled upon—the opera is much more concerned with Aschenbach’s “Apollonian” nature (the careful, considered, intellectual nature) slowly giving over to the Dionysian without understanding the why or wherefore of his desperate, fatal attraction.

The psychology of the Aschenbach character is genuinely fascinating, but the operatic form seems particularly unsuited to telling it. Librettist Myfanwy Piper tries gamely to translate the thoughts of Aschenbach in Mann’s novella into long, dry, heady monologues with piano-only accompaniment, but these often veer into pseudo-intellectual ramblings and dry philosophizing without really illuminating the tortured thoughts of the character. The difficulty of translating a character’s inner thoughts into sung recitatives seems to have defeated Ms. Piper’s best efforts.

Britten’s music is, as always, inventive and occasionally thrilling. There is a wonderful sense of morbidezza-like foreboding in the music from beginning to end. Sometimes it feels a bit under-orchestrated in the most emotional moments, particularly those as Aschenbach begins to realize the seriousness of the plague of cholera in Venice that will soon take his life.

But the music surrounding the doings of the boy Tadzio, beautifully played and danced by the excellent Sam Zaldivar, is lustrous, sensual, athletic, and quite delicate. The final scene of the opera, with Tadzio dancing in front of the fearsome sun as Aschenbach expires, is exquisite.

Much credit goes to the superb choreography of Kim Brandstrup, capturing the spirit and zeal and athleticism of Tadzio and his group of compatriots.

The character tenor John Graham-Hall (most recently Triquet in the Met’s Eugene Onegin) takes the opportunity of playing a leading role here and throws himself into the character with brilliant singing, phrasing, and some committed, focused acting work. It should be noted that he never seems to tire in this long and exhaustingly difficult role. Still, for me, Graham-Hall and Warner seem to emphasize the fussy, neurotic aspects of the character’s behavior at the expense of seeing the psychological fall of a man who begins the opera as a grounded, famous writer.He seems too much the cranky old complainer from the very beginning, so that his psychological journey into obsession is a not particularly long one. Graham-Hall’s Aschenbach is so self-absorbed that we feel little sympathy for his ramblings on the nature of beauty and art. While I admired the performance, it was a completely objective admiration. I felt very little. I kept waiting for him to yell from his beach chair “You kids get off my lawn!”

Baritone Andrew Shore is excellent in his many roles—particularly as the vulgar Elderly Fop, the darkly menacing Old Gondolier, and the over-solicitous hotel manager. Besides his superb dancing skills, Zaldivar delivers a Tadzio of great and ambiguous charm in his silent role. His expressive face never gives too much or too little.

The large ensemble and the Chorus of English National Opera are admirably focused and have been finely shaped into thrilling stage pictures under Warner’s direction. Conductor Edward Gardner gives great attention to detail in bringing out the unique sounds of Britten’s score.

In Death in Venice, Britten again explores the thoughts and actions of a troubled loner on a stormy psychological sea, and also examines the nature of innocence and the nature of beauty. But unlike Peter Grimes or Billy Budd, this opera feels more standoffish than inviting. Aschenbach’s arrogance and self-absorption overwhelm his vulnerability and humanity.