Perhaps there are not that many people in the world who would look at a CD cover and think “Oh, goody, goody! A libretto by Eugène Scribe I’ve never come across before!” Scribe, a prolific creator of many forms of popular theatre in Paris, wrote the libretti for the most famous French grand operas but also produced works in many other genres. I knew I could expect a lot of variety, incident and entertainment from Ali Baba ou Les Quarante voleurs (“Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves”) and I was not disappointed.

Scribe wrote this piece in collaboration with another popular French dramatist and librettist, who went by the name of Mélesville. Ali Baba had its premiere in 1833 at the Paris Opéra, with music by the Italian born Luigi Cherubini, his last work for the stage, which actually uses a lot of music he had written for another opera, never performed, decades earlier.

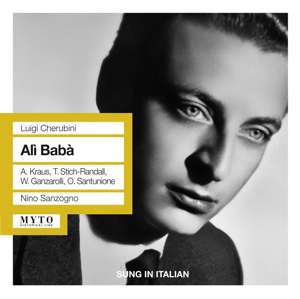

This live recording on two CD’s from La Scala in 1963 is performed in an Italian translation. It is a pity for such a little-known work that there is neither summary nor notes nor libretto included; however I found the original French libretto online.

Cherubini is probably best known today for his opera Médée but produced numerous other works and was appointed director of the Paris conservatoire of music where one of his pupils was Berlioz, who did not appreciate Cherubini’s disallowing “incorrect” modulations and harmonic effects.

Cherubini had visited Vienna and met with Beethoven, who tremendously admired the Italian-born composer. In Ali Baba you can really hear the influence of Cherubini on the lighter parts of Fidelio. Cherubini did not return Beethoven’s admiration, however, his only comment on Beethoven’s late style was that it made him want to sneeze.

The overture to Ali Baba starts in a much more startling and original way than one might expect from such a seemingly conservative composer, with very unusual effects from trombones, cymbals and triangles, in the sort of “Turkish” music style Beethoven and Mozart had used in various works. Mendelssohn, though admiring the many beauties of Ali Baba, was astonished and disgusted by the “noisy” and “brash” writing for brass and percussion.

Ali Baba is a sort of hybrid opera-ballet, with about a third of the work given over to dances.It is not exactly a comic opera, but not terribly serious either, obviously intended to entertain and delight with music and spectacle, based on a famous tale from the Arabian Nights.

Nadir, a poor wood-cutter, is in love with Delia, daughter of a wealthy merchant, Ali Baba, but he has betrothed his daughter to the rich collector of taxes, Abul-Hassan.

In the prologue of the piece, Nadir is out in the woods lamenting his unhappy love in an opening aria that has the best singing of the whole performance from the young Alfredo Kraus, alternately lyrical, heroic and despairing, with many ringing high notes that bring the house down in a big ovation. Absolutely smashing and worth getting the CD’s just for this aria.

Nadir hides and watches as a band of thieves approach the nearby cave. Their leader cries “Open sesame” and the cave opens to reveal a treasure trove of stolen loot, gold and jewels of all kinds.

The thieves take what they fancy and then dance about, the expensive trinkets’ jingling and jangling depicted in the music in a most jolly manner. They leave. Nadir repeats the “Open sesame” incantation and helps himself to riches beyond his dreams.

Act One is in Ali Baba’s house. Delia is unhappy about having to marry Abul-Hassan, for she returns Nadir’s love. She laments her situation in a lovely aria, sung by soprano Theresa Stich-Randall in a voice that is quavery and acidic at times, but always used with excellent musicianship and phrasing.

Nadir turns up with money,horses, carriages, slaves, diamonds, rubies, and offers her father whatever he wants if only he will let him marry his daughter. Ali Baba cannot turn down this offer, and when Abul-Hassan arrives he informs him that the wedding is off.

This infuriates Abul-Hassan, who threatens to tell the authorities about the forty bags of expensive imported coffee he knows Ali Baba has but has not paid tax on. Much huffing and puffing from the excellent buffo Paolo Montarsolo as Abul-Hassan in the ensemble that ends the act.

Almost the whole of Act Two is taken up by a long ballet in honour of Delia’s forthcoming marriage. The dance music is varied and very enjoyable as conducted by the excellent Nino Sanzogno. Ali Baba insists Nadir tell him how he got so rich all of a sudden and Nadir informs him about the “Open Sesame” cave.

Delia, on the way to get ready for the wedding, is abducted and no one knows what has happened to her. Nadir swears to find her and have vengeance on whoever has carried her off.

Act Three is in the robbers’ cave. A comic trio of bandits celebrate their exploits. Delia has been kidnapped by the bandits and expresses her sorrow in another lovely aria. Hearing someone coming, she hides. It is her father, who is delighted to open the cave and find all this money and riches.

He glories in this good fortune in an aria full of more tinkling and jingly orchestration and onstage effects, which as sung by the warm toned Wladimiro Ganzarolli, bears strong similarity to Rocco’s “Gold” aria in Fidelio.

The thieves come in and catch him though, and are about to kill him when Delia steps forward and informs them that he is her father, a rich merchant, and they will pay a lot of ransom. The thieves agree.

Act Four is back at Ali Baba’s house, where Nadir is in despair at the loss of Delia. The lovers are joyously re-united and Ali Baba entertains the thieves with another long ballet of dancing slave girls. Hearing approaching soldiers, the thieves empty out the forty bags of imported coffee and hide in them. It is Abul-Hassan, still angry at being jilted, and his men, who take vengeance on his rejection by setting fire to the bags of coffee, thus unknowingly killing all the thieves and bringing the work to a happy conclusion.

A live recording of a very obscure French opera in Italian translation with a lot of dancing and therefore considerable stage noise, in not very good sound, that does not come with a libretto or any notes, may not be, I quite see, everyone’s cup of tea but I enjoyed it enormously.

The wonderful Kraus is also the star of another live performance

from ’60’s Italy, Bellini’s last opera I puritani, from Modena in 1962. The sound on these two CD’s is even worse than in Ali Baba, the orchestra is scrappy and some of the singing provincial, but I enjoyed it nonetheless.

Puritani is another opera by an Italian that had its premiere in Paris, this time at the Théâtre-Italien, in 1835, with a cast of four superstars, the soprano Giulia Grisi, the tenor Rubini, the baritone Tamburini and the bass Luigi Lablache.

A libretto by Count Carlo Pepoli is based on a play “Round Heads and Cavaliers” which was in turn loosely based on a work of Walter Scott, which is perhaps why the full name of the opera, often found on old scores and libretti, is I Puritani di Scozia but the scene is given as “Plymouth” (that’s not in Scotland).

Anyway, during the English Civil War,at this fort in Plymouth, heroine Elvira, daughter of a Puritan, has fallen in love with a Royalist, Arturo, although affianced to another Puritan, Riccardo.

Elvira is delighted when her uncle Giorgio gives her consent for her to marry the man she loves and everything is all set for the wedding when Arturo discovers that the mysterious lady prisoner in the fort is the widowed queen of the executed Charles I.

He feels it is his duty to take her to safety, and so doesn’t turn up for the wedding, and Elvira, seemingly jilted at the altar, loses her reason. Arturo is condemned to death in his absence for releasing the captured queen, but comes in secret to see Elvira.

When she learns he still loves her, her wits are restored.Arturo is discovered, and is about to be put to death, but news arrives that the new government has announced an amnesty for their Royalist enemies, and all ends happily.

The conductor Nino Verchi leads a performance which does not really do Bellini’s grandiose orchestral writing justice, with a lot of flubs in the many crucial passages in this opera for horns. The baritone Attilio d’Orazi is rough and uncertain in pitch, but does manage a crowd-pleasing high note in his exciting duet, “Suoni la tromba” with excellent bass Raffaele Arié.

Mirella Freni is not a dazzling coloratura along the lines of Callas or Sutherland in this role, but sings Bellini’s beautiful melodies with lyricism and pathos, particularly lovely and touching in the lament at the end of the first act.

Kraus is phenomenal and his performance is once again worth the price of admission, with superb vocalism and intensity of feeling all the way through. The best bit is the duet of Freni and Krauss at the end of the piece, with stratospheric high notes from both of them. The crowd goes nuts.

No libretto or notes with these CD’s either, though those are much more easily found for Puritani than Ali Baba.