Philip Glass’s 25th opera The Perfect American was originally commissioned for New York City Opera during the aborted regime of Gerard Mortier. When his hiring fell through in 2008, Mortier and his planned City Opera projects headed for Teatro Real Madrid, where the piece opened in January 2013. The story tells of the final days of Walt Disney as he was dying of cancer in 1966, based on the novel Der Konig von Amerika by Peter Stephan Jungk, a fictionalized account of Disney being stalked by a fired employee who sought to unionize Disney’s employees and get them the credit they deserved for much of the actual drawing of the Disney characters. (Saving Mr. Banks it ain’t.)

Glass has written one of his most striking scores for this opera. It opens on a long, sinuous low note punctuated by sharp percussive cracks, repeating in groups of four. What follows retains the expected propulsive repetitions, but here Glass seems to be discovering new textures and colors, especially in the scenes where Walt waxes longingly for the easy days of his past. There are musical allusions to the 1930s and 40’s and sensitive, sad sounds that emphasize the melancholy side of the characters.

I thought I heard an homage to Glass’s compatriot John Adams, and perhaps my favorite music was the semi-Wagnerian “Happy Birthday, Walt” late in Act One. There are also moments of frightening and sudden chords when Walt is experiencing nightmares, especially the one where he remembers being attacked by an owl at the age of seven. Later, this same motif occurs when Walt’s birthday is interrupted by the child/shaman Lucy wearing owlish accouterments. This owl motif, though dramatically hamhanded, is musically fascinating.

The problem here, and it is a major one, is a cardboard libretto by Rudy Wurlitzer. It certainly must have been a trial to shape the Jungk novel into a two-hour opera, but Wurlitzer has not found a way to make these characters or these situations human. Disney (and, actually, everyone else) does nothing but spout platitudes and clichés. There is no subtlety, no subtext whatsoever, and the only real moments of conflict are the brief scenes between Disney and the fired employee Dantine and, of course, when anything resembling an owl (there it is again!) shows up.

The scene that ends Act One, where Disney has a conversation with the animatronic, speaking puppet of Abraham Lincoln, should have provided a great opportunity for some inventive, maybe humorous exchanges. Instead, we find Disney spewing racist venom about blacks and hippies and actually questioning Lincoln’s moral decisions. I found myself wishing that Lincoln would deck him. Instead, the scene peters out, another opportunity missed.

Disney is here portrayed as a right-wing zealot, a vehement racist, and an opportunist who used the work of his underlings to achieve his fame. We are frequently reminded that ”more children know Mickey than Christ”; Disney claims responsibility for “creating” Ronald Reagan, and, when a boy compares Disney to God, the filmmaker does not demur.

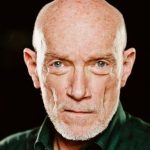

The production values are excellent. Video designer Leo Warner and lighting designer Jon Clark create a genuinely magical atmosphere, using rudimentary drawings of Disney characters and cartoon-like visions of Disney’s home and hospital room in projections thrown upon gossamer fabrics. All the settings are enormously enhanced through the stunning mime and dance work of the Improbable Skills Ensemble. The excellent set and costume designs are by Dan Potra.The performances range from very good to excellent. Christopher Purves throws himself completely into Walt Disney, singing with confidence and power, and manages to breathe some life into the generalized avuncular affability forced upon him by the libretto. David Pittsinger gives us a stentorian and appropriately businesslike Roy Disney, again hampered by a libretto that fails to give him an individual personality.

Among the fine supporting cast, Janis Kelly stands out as Disney’s private nurse (and implied romantic interest), both her singing and acting affecting and one of the few moving elements in the opera. Donald Kaasch makes the most of his moments of conflict as the unjustly fired Dantine, who implies that he had a significant part in the creation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, but was fired for his political stance and given no credit as the Disney machine rolled past him.

Glass specialist Dennis Russell Davies seems completely at home with this music, and conducts the Coro y Orquesta del Teatro Real in a sensitive but propulsive performance that breathes real life into Glass’s distinctive score.

All the elements are in place here for a fine and possibly lasting operatic experience, but the story simply doesn’t hold up. It’s a cartoon, and, yes, we “get” that Disney’s mission and career were about creating cartoons, but his life certainly wasn’t one.