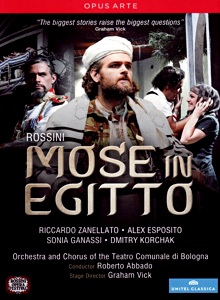

Somewhere around the early 1980’s, stage directors realized that the odious theatre practice of “audience involvement” was over. Waaay over. Apparently, Graham Vick was absent that day. So, the first ten minutes of his production of Rossini’s 1818 opera seria Mosè in Egitto are excruciating. Vick has set the opera just after one of Moses’ plagues against Pharaoh, here some sort of 9/11ish event, has occurred. As the opera begins, bloodied and dazed Egyptians of the chorus meander through the audience, forcing embarrassed and confused patrons to look at photos of their “disappeared” loved ones. Even on DVD

, it is very difficult to watch the audience members trying to watch the opera, annoyed by being forced to be a part of the action.

It’s a real shame, because this evolves into a very successful, well thought out production, fascinating in design and quite well sung, set in the present-day Middle East. The production premiered in August 2011 for the Rossini Opera Festival Pesaro, and is staged in the Arena Adriatica, a converted basketball stadium. The upper areas of the set represent the throne room and palace areas of a despot (Pharaoh), while the underbelly of the staging contains the detritus of the revolutionaries (Israelites) including computers, beds designed for torture, broken down vans, and explosives. Set and costume designer Stuart Nunn has done a splendid job in making the updating a consistent and viable concept.

The story of the opera is the familiar tale of Moses’ attempts to convince Pharaoh to let the Israelites depart, sending curses upon Egypt when they are refused. Finally, there is the final escape with the parting of the Red Sea. (Apparently, at the Naples 1818 premiere, the stage machinery for the parting was so laughable that Rossini removed it from the stage; the effect was much more successful in a revival the following year). Rossini and his librettist Tottone added an interesting love subplot, where Osiride, son and heir of Faraone, has fallen in love with the Jewish girl Elcia. His fear of losing Elcia to the Israelite exodus spurs him to twice oppose his father’s decrees to release the Israelites and end the plagues.

The most successful viewpoint of Vick’s production is that he refuses to take sides: both the Egyptians and the Israelites are capable of both kindness and cruel violence. Moses is a fiery revolutionary here, perhaps an Israelite version of a jihadist, supported by his gentler brother Aronne. Faraone is torn between arrogant authority and the real desire to save his people. His wife, Amaltea, is here presented as a secret convert to Judaism. The desperate, secret passion of Osiride and Elcia brings the religious and the personal into irreconcilable conflict.

Vick’s ending is stunning. As huge panels fall to represent the Red Sea parting, an Israeli tank is revealed blasting away and destroying the pursuing Egyptian army. Then, in a brilliant coup de théâtre, Vick has a young Israeli soldier climb down from the tank to offer a chocolate bar to a young Egyptian boy. We have just seen the Egyptian boy strap an explosive belt under his tunic. As the two meet, the blackout happens. The audience holds its collective breath before a major ovation erupts.

Happily, the production illuminates the music under the superb conducting of Roberto Abbado. He is remarkably sensitive to every nuance in Rossini’s rich score, and even musical moments likely meant to show off coloratura effects are infused with meaning and power. I have never felt a Rossini opera so dramatically cogent as this one. As with only the best bel canto, every ornament and trill feels spontaneous and necessary to the storytelling.

The entire cast sings with equal measures of tonal beauty and dramatic commitment. Alex Esposito gives us a multi-faceted Faraone, blustering and arrogant on one hand yet agonized and confused on another. He is convincing both as an absolute monarch and as a human being wrestling with his desire to serve his people well. The tone of his singing might be a bit darker for even more success, but he sings with power and variety, and his physical characterization is “every inch a king.”The tenor Dmitry Korchak sings his son Osiride with fearless abandon, the voice flexible and passionate, though he seems to force the higher notes of the role. Still, he hits them all and sings with unfailing accuracy and clarity. Soprano Olga Senderskaya as the King’s consort Amaltea gives a dramatic, committed performance and her bell-like soprano mixes beautifully in the many quartets and ensembles. There is a lovely ease to her singing, even in heavily dramatic moments. Tenor Yijie Shi as Arrone has a gorgeous, clear sound but seems a bit uncomfortable in his acting.

Riccardo Zanellato is an impassioned and powerful Moses, fierce in his defense of his people. His voice does occasionally become wooly, and one might wish for more variety in his approach and perhaps a bit more sensitivity. Still, he is fearsome in his rages at Faraone’s duplicity. By far his finest moment is the final act prayer “Dal tua stellate soglio”, one of Rossini’s finest arias.

This brings us to mezzo Sonia Ganassi as Elcia. It seems to me that this is the production’s only casting misstep, as she sounds and looks matronly for the role of the young Elcia. She has some stunning vocal moments, though, and must be commended for her work in ensembles, where her voice blends perfectly with her partners. This is most exquisitely evident in the quartet “Mi manca la voce” in Act II, where she spun magnificent sounds blending with the voices of Osiride, Arrone, and Almatea matching the brilliant harp accompaniment. The effect was both moving and ethereal.

Kudos to the fine Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro Communale di Bologna and Chorus Master Lorenzo Fratini for the splendid playing and singing as well as clear diction and commitment to the production choices. Now please, Mr. Vick, spare them the awful task of breaking the fourth wall at the beginning of this performance. Had I been in this audience, I might have either walked out or told the bloody Egyptians to get out of my face.