Puccini’s evening of one-act operas Il Trittico seems to be riding a wave of popularity over the last few years, with a new production at the Met and several high-profile productions in America and Europe. And while, for me, the “gold standard” in this work has always been the 1981 Met telecast

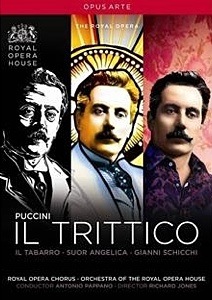

featuring an on-fire Renata Scotto in all three female leads, recent productions are beginning to look for new settings and viewpoints connecting these three very different short operas. One of these, and for the most part a very successful one, is the Royal Opera production from September 2011, recently released on DVD

from Opus Arte.

The first and best reason for seeking out this DVD is the brilliant conducting of Antonio Pappano and the playing of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Pappano’s work here brings real meaning to the term “revelatory”: I heard colors and textures, particularly in Il Tabarro, that gave the opera far more depth and complexity than I had noticed before. Pappano’s propulsive, passionate reading significantly enhances the emotional power of the first two works.

Then, switching styles completely, he brings a real sense of raucous fun to the farcical antics of Gianni Schicchi. The conducting is masterful throughout, and Pappano and the orchestra work together seamlessly. I found myself replaying several sections of this DVD over and over again, marveling at musical moments that were uniquely moving.

Many of those moments are in the first opera, Il Tabarro (The Cloak), Puccini’s grim tale of stevedores and their women trapped in a life of backbreaking work. Despite one serious casting problem and some odd staging from director Richard Jones, the performance has real power, thanks to glorious singing and acting from Eva-Maria Westbroek as the frustrated wife Giorgetta and Aleksandrs Antonenko as her secret lover Luigi.

Westbroek gives a gutsy yet sensitive performance, vocally powerful in the climaxes and shimmering in quiet moments. Antonenko seethes with resentment at his endlessly demeaning work, savoring deeply his few moments of pleasure with Giorgetta. The “Belleville” duet is simply stunning, both singers pouring forth golden sounds as they express their powerful longing for the life they once had in the city. The tragedy of the story is made all the more shattering when this duet allows us to see and hear what “might have been” for these characters. Irina Mishura is a fruity-voiced and affecting Frugola.

Alas, the Michele, Giorgetta’s older husband and the owner of the barge where the action takes place, is placed in the hands of Lucio Gallo, the baritone whose voice always seems one size too small for… well… everything he sings. His physically slight, emotionally reticent Michele is sung competently, but he seems unable to match either the power of the music or the passion of his colleagues.

The sense of being trapped in a life the stevedores cannot escape is much enhanced by the claustrophobic set of the designer Ultz; D. M. Wood’s lighting is hauntingly effective. Jones’ staging works very well until the very end of the opera, where the murder of Luigi and the discovery of his body by Giorgetta are handled with astonishing clumsiness.

Rather than hiding Luigi’s body under the cloak he is wearing, Jones here has Michele cover Luigi’s prone body with the cloak, then lie on a lower level, talking to Giorgetta as if it is he sleeping under the cloak. It really doesn’t work at all, and one suspects that this is a misguided attempt to tie the opera with Gianni Schicchi, when Gallo also lies under a bed pretending to be Buoso Donati (more on this later.)

Director Jones sets Suor Angelica not in the usual cloistered convent, but instead in a children’s hospital circa 1960, where the nuns serve as nurses and Angelica is the hospital’s “natural herb remedy” specialist. The presence of sick children in rows of beds is an interesting but distracting conceit, and again Jones’s staging of the end of the piece is problematic. Instead of the dying, solitary Angelica experiencing a redemptive vision of her dead child, here we have Angelica flailing about in the presence of a number of nun/nurses trying to control her.

And no vision of the dead child here—one of the sick children comes up to Angelica, she hugs him, and then the other nuns wrench him from her arms. Angelica dies in a chair, and a bed sheet is thrown over her lifeless body. While this provides a grim ending, it is in no sense redemptive.

Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho, substituting for an indisposed Anja Harteros in the title role, sings beautifully for the most part, though she seems stretched in the higher reaches, particularly the final note of her aria “Senza mama” and in her desperate pleadings to the Madonna at the end.

But this is definitely a soprano to watch—I have the feeling that she is not yet technically complete, but will be a formidable Puccini heroine in a very short time. Jaho’s Angelica seems a bit too stoic in the early section of the opera, but bursts forth with emotional power and fury in her scene with the Principessa (a wildly over the top, neurotic characterization by Anna Larsson).

Angelica’s collapse at the news that her illegitimate son is dead is Jaho’s most moving moment, and, led by Pappano’s driving, pulsing reading of the score, she finishes the opera with wild abandon and full commitment. It is a tribute to both Jaho and Pappano that the emotional power of this music is undiminished by the peculiar staging.

Jones saves his best work for Gianni Schicci, arguably the most popular of the three as Puccini’s only comedy. This production, set in the late 50’s, features a terrific ensemble cast of singing farceurs who set just the right tone of comic greed and religious posturing. Gallo in the title role is much more in his element here, and his impish qualities work well in this character, though again one longs for a more sizeable baritone to fill Schicchi’s bluster.

Ekaterina Siurina, looking gorgeous in a red and white striped dress, sings Lauretta’s “O mio babbino caro” with limpid sweetness. The energetic and delightful tenor Francesco Demuro brings just the right youthful exuberance to Rinuccio. Standouts in the excellent ensemble include Elena Zilio as a hilariously pompous Zita and Marie McLaughlin as an oversexed La Ciesca.

Adding to the fun are the humorously garish set by John McFarlane and delightfully quirky costumes by Nicky Gillibrand.

This DVD set (each opera in its own case and including a very interesting essay on the Trittico by George Hall) is certainly a welcome and important addition to the list of available recorded works of Puccini. It is an excellent, musically superb rendition that could have been an absolute triumph except for some of the flaws listed above.

Still, I will definitely return to this Royal Opera production, which offers far more pleasures than drawbacks. It’s worth the price of the DVD for Pappano and the orchestra alone, and if you are one of the many who find Tabarro the weak link of Il Trittico, this is the production that will change your mind.

Comments