Sometime in 1753, Frederick The Great of Prussia, following a tiff with his great friend Voltaire, began writing an opera libretto in French prose that was to elucidate his ideas about the role of an enlightened monarch. Though deeply into military preparations for the soon-to-be Seven Years War, Frederick sought to portray himself as a benevolent, incorruptible monarch espousing the Enlightenment ideas of gentility, generosity, and religious tolerance.

He chose as his subject Montezuma, the 16th century emperor of the Aztecs in Mexico, picturing the emperor as an idealist, just monarch too innocent and generous to save his empire from the clutches of the venal Spanish conquistadores under Cortes. Frederick turned his drafts over to his court poet, Giampietro Tagliazucchi, for translation into Italian verse. It then went to the royal Kapellmeister Carl Henirich Graun, who produced the score in 1755. Except for his oratorio Der Tod Jesu, Graun slowly fell out of favor as an operatic composer until he was little more than a footnote. Not much was heard of Montezuma until Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge featured a few arias from the opera on disc in 1966.

In 1981-82, interest in the piece by musicologist Hellmut Kuhn and dramaturg Georg Quander (who would eventually adapt the piece into German) began in collaboration with Deutsche Oper Berlin. Kuhn and Quander managed to produce a performance version of Montezuma, slashing the far-too-long piece of many of its recitatives and da capo arias. Conductor Hans Hilsdorf, as close to a Graun specialist as one could find at the time, joined in working on the musical adaptation.

Stage director Herbert Wernicke chose to set the opera in the place and time it was written—1755 in the Sanssouci Palace—with Montezuma clearly portrayed as Frederick himself. During the Sinfonia, the first stage picture we see is Montezuma-as-Frederick playing the flute in front of the other characters of the opera in a staged reproduction of Menzel’s painting Flotenkonzert in Sanssouci. No attempt is made to portray the Aztecs in native garb; they are all dressed in European baroque costumes and perform in the posing performance traditions of the time. All the vocally high-lying Aztec male and female characters, with the dearth of countertenors available in the early eighties, are cast as women. The castrato character of Montezuma is taken by a mezzo-soprano.

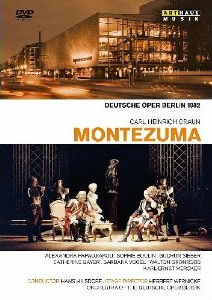

The production opened to some apparent success in November 1981; it also was performed in 1982 in Sweden and then filmed for DVD at Bayreuth. So now, Arthaus Musik has released the DVD of this thirty-year-old production.

Wernicke’s all-baroque-all-the-time konzept strains credulity from the beginning. Yes, the connection between Montezuma and Frederick is made clear the moment that we see the tableau of the Menzel painting; but to have all the Aztec characters (Montezuma, Eupaforice his bride, Tezeuco his advisor, Pilpatoe his general, and the queen’s confidante Erissena) played by bewigged women using the stock gestures and poses of the 18th century stage simply negates the cultural clash that is at the heart of the story.

It does not help that the first act is musically and dramatically the weakest part of the opera, mainly consisting of Montezuma philosophizing about the nature of enlightened kingship and ignoring the warnings about the impending Spanish invaders. The first act’s music is serviceable, workmanlike, but never reaches any level of inventiveness or ravishing beauty. Montezuma begins to come to life with the arrival of the Spanish, when the clash between the natives and the colonialists begins to flesh out.

But even here, Cortes and his General Narves are portrayed as mustache-twisting, cartoonishly evil villains. Apparently not noticing this until deep into Act Two when he is arrested in his own palace, Montezuma seems hopelessly naïve and no challenge at all to the invaders.

There are some genuinely fine arias in the piece, especially Eupaforice’s “Nichts besanftigt meine Qualen”, where she sings of her fears and troubled prophecies of her future; and Montezuma’s splendid recitative and aria that begins Act Three, “Gott, welch schreckliches Schicksal… Ach, des gestrengen Schicksals.” Here, Graun finds the character’s emotional center and portrays it in vivid and powerful music.

The music of the third act snowballs nicely toward its tragic conclusion with the destruction of the Aztec Empire. But too much of the first two acts are musically disconnected from the characters’ emotions and actions, not helped by the performers’ use of stylized gesture and stance.

Alexandra Papadjiakou leads the cast as Montezuma with her rich and flexible mezzo. She certainly gives the finest and most consistent singing of the evening, even trying vainly to sing some life into the character’s philosophical meanderings. Limpid soprano Sophie Boulin gives a committed performance as Queen Eupaforice, but the voice turns shrill and wiry in the highest reaches of her extensive coloratura.

Catherine Gayer as the lord chamberlain Tezeuco seems trapped by the baroque style; her stock gestures and strange facial expression almost comic. Barbara Vogel’s soprano seems too light for the music of the imperial general Pilpatoe, and she, too, adapts a single stance and facial expression throughout that does not match the character or the musical expression. Among the Aztecs, only Gudrun Sieber in the small role of Erissena has the ideal, bell-like vocal quality for this music and seems at ease and comfortable in the character.

Walton Gronroos as Cortes and Karl-Ernst Mercker as his captain Narves have little to do but threaten and bluster, but they do so with commitment and power. Mercker does particularly well with his taunting Act One aria “So seht in diesen Mauern”, though he chugs his way heavily through some of the runs. Interestingly, these characters speak Spanish when they are in conversation with each other.

Hans Hilsdorf lovingly conducts the Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, having made significant contributions to the orchestration of this adaptation.

I suppose it is a positive that so many opera DVDs are now being produced. Thus, we have the opportunity to experience this interesting rarity, though it seems only a decent and serviceable production of a decent and serviceable opera. I would like very much to see Montezuma performed in a production where the native setting and costumes were used—apparently this was done in 2010 at the Edinburgh Festival and Teatro Real Madrid (though even this was not well-received).

The Montezuma-Cortes clash (as well as the Atahualpa-Pizarro clash among the Incas to the South) seems a truly operatic subject. In fact, I’ve always thought Peter Shaffer’s play The Royal Hunt of the Sun would make a terrific opera in the right hands. But Graun’s Montezuma is really more about Prussian politics than issues of conquest and colonization.

Comments