“This is the end of Western culture,” Richard Strauss proclaimed after a rehearsal of his penultimate opera Die Liebe der Danae, in Salzburg in 1944. The octogenarian composer, increasingly on the outs with the Nazis and switched off from contemporary music currents, could well have identified with his protagonist Jupiter, a once-mighty God caught up in an off-kilter world he finds impossible to understand.

Danae may be Strauss’ most self-referential opera, and is certainly among his most neglected.

The composer never saw a full-blown staging in his lifetime due to a failed assassination attempt on Hitler that led to the cancellation of the Salzburg Festival and the scheduled premiere under Clemens Krauss. The first performance took place three years after the composer’s death, as tastes were shifting toward more stripped-down, abstract music and away from the kind of Classical subjects so eagerly embraced by the Third Reich. The score moldered until Regie directors in the late 1990s began to see possibilities in its portrayal of a bankrupt state at zero hour.

A DVD of the most recent revival, by Kirsten Harms for Deutsche Oper Berlin, reveals the opera to be a sumptuous, predictably Straussian adaptation of Greek myth that’s perhaps a bit too clever for its own good and doesn’t really take off musically until the final act. At least part of the problem is a weak libretto by Joseph Gregor that reduces most of the lead characters to cardboard cutouts and doesn’t seize on some of the dry wit that the composer had in mind. On the plus side, this opera contains some of the most radiant music that Strauss composed for male voices, plus pleasing choral writing to break up the arias, duets and trios.

The action revolves around Jupiter’s attempts to seduce Danae, daughter of Pollux, the indebted King of Eos. To win his prize, the god swaps identities with Midas, whose touch turns anything to gold, and forces him to act as his messenger. Danae turns down the promise of riches, to her father’s consternation, and falls for the real Midas, even though she’s doesn’t know his actual identity. The opera concludes with an autumnal bit of leave-taking during which Jupiter acknowledges he’ll never experience the gift of true human love.

Harms’ production looks like it’s set in 1940s and is neither enchanting or whimsical. The most prominent scenic element is an upside-down piano that hangs inexplicably over the stage and is used at one point to drop sheets of music to symbolize gold raining down from the skies. During the third act, the walls of the set crumble, a metaphor for the Third Reich and the simple life ahead for Danae and Midas. There are smoke effects and glittery, faux metallic costumes worthy of a cheap Las Vegas revue but not enough probing direction to make the characters really pop out or make their plights resonate with an audience.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GmanA7gRUwk

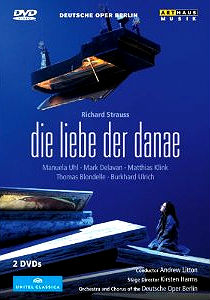

The three leads are confronted with demanding roles that require projecting over thick orchestral accompaniment. As Jupiter, American baritone Mark Delavan strains in the upper register but conveys a real sense of nobility in the opera’s final scenes, when he gives a benediction and bids farewell to the mortals in a moment reminiscent of Die Walkure. Tenor Matthias Klink faces similar vocal challenges as Midas but more than holds his own in an extended Act 2 duet with Danae culminating the rapturous “Herrliches Spiel! Vollendeter Traum!” Best among the principals is soprano Manuela Uhl in the title role. Though her tone is somewhat unfocused and glassy at the top, Uhl’s attention to detail and natural unspooling of Strauss’ lyric lines save some of the duller scenes in the first two acts.

American conductor Andrew Litton has become something of a standard-bearer for rare Strauss operas. He keeps the Berlin orchestra moving throughout the rhythmically challenging score, laying it on thick during interludes but pulling back at the right moments to reveal a delicate passage or frame a meditative moment. The Deutsche Oper chorus acquits itself well.

The program book notes that Strauss told Krauss that he strived to write music that was like hard-cured sausage, and would prove both substantial and durable. Danae kind of lives up to that odd analogy. It’ll never become a staple of operatic diet but may provide a pleasant discovery behind the salad crisper.