Giovanni Simone Mayr was one of the most important musical figures of his day, a man Rossini referred to as the “father of Italian opera” whom Napoleon personally lobbied to come work in Paris. Though he wrote nearly 70 operas and taught Donizetti and Bellini, the Bavarian-born composer had the misfortune of hitting his peak in the era between Mozart and Beethoven, just as the bel canto movement was opening up new musical and dramatic possibilities. By the 1830s, with operas like Norma the rage, Mayr was slipping out of favor, viewed as something of a fusty relic even in his adopted homeland of Italy.

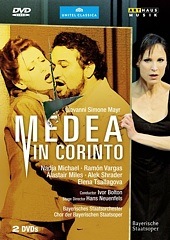

It wasn’t until 1963 that Mayr won a reappraisal, when Medea in Corinto was revived in Munich for his bicentennial. The sturdy score blending Italianate lyricism and Classical harmonies proved something of a revelation, attracting singers such as Leyla Gencer and getting sporadic revivals during the 1970s. The work finally had a coming out at a major repertory house last year, when the Bavarian State Opera mounted a provocative new production that’s now available on DVD.

Mayr originally intended to set Euripides’ tragedy as an opera seria for the 1813 season at Naples’ Teatro San Carlo but was talked into making changes by theater management sensitive to the tastes of French authorities who then ruled the city. Recitatives were scrapped for more fluid accompaniments and the part of Giasone (Jason) rewritten for tenor from mezzo soprano. Isabella Colbran essayed the title role to great acclaim at the premiere, and Giuditta Pasta made it something of a personal calling card in subsequent years.

While the work has considerable merits, it’s difficult for a contemporary listener to assess it without making invidious comparisons. Mayr and his librettist Felice Romani (who also wrote the texts for Norma, Anna Bolena and L’elisir d’amore, among others) paint vivid psychological portraits that anticipate the potboilers of Donizetti, Bellini and early Verdi. The taxing (and at times, quite long) arias have the elegant formalism of Mozart and Gluck. Though the score is variegated and dramatically complex for its day, it both lacks the sublime nobility of a Clemenza di Tito and the audaciousness of Cherubini’s 1797 take on the same myth. The onus is clearly on the performers and director to elevate the work above museum piece status.

Director Herbert Neuenfels sees the Medea myth as a character-driven study of emotions that should resonate with contemporary audiences. Medea’s agonized decision to kill her children is portrayed here as an act of fear and desperation—a sliver of humanity in a corrupt, totalitarian Carthage Corinth ruled by a particularly venal Creon.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p62TN_j4ysI

There’s a predictable amount of gratuitous brutality and some stock regie nonsense that suggests Neuenfels doesn’t entirely trust the material. Hymen and Amor are silent characters who hang over scenes like annoying street mimes while musicians emerge on stage at other moments to italicize what’s being sung, such as a lurking solo violinist during Medea’s big Act I turn “Son sola.” Costumes run the gamut from ancient Greece to modern-day formal dress, including a witch doctor outfit for Medea that’s just plain silly.

It’s left to the cast to make the strongest case for the work. German soprano Nadja Michael deploys her huge, dark voice to great effect the title role, turning in a charismatic and committed performance despite very occasional intonation problems at the top. Tenor Ramon Vargas can’t hide the effort needed for Giasone, a role that sits a little low for him, but spins beautiful lines in arias such as “Di gloria all’Invita.” Alistair Miles is a menacing Creon while tenor Alek Schrader does a strong turn as the Athenian King Egeo, a character Romani added to give the plot more gender symmetry.

The biggest star, however, is conductor and early music specialist Ivor Bolton, who extracts considerable color and dramatic heft from the score and leads a spirited performance by the Munich pit orchestra. The nuances and intricacies reveal Mayr as a true innovator, not just a transitional figure whose career was bookended by musical giants. Forty-five minutes of bonus interviews with the cast and production team and with Mayr scholar Rainer Rupp make the release a noteworthy addition for any music lover guilty about giving short shrift to repertory from the earliest years of the 19th century.