In a post Jimmy Swaggart, Jim Bakker, and Jerry Falwell era and with politicians spouting that natural disasters are God’s way of telling us to reduce the national debt, Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry seems more prescient than even he probably intended. A satirical novel about the excesses of the evangelical movement in the early part of the 20th century, it inspired a play, a movie starring Burt Lancaster and Jean Simmons, and now an opera

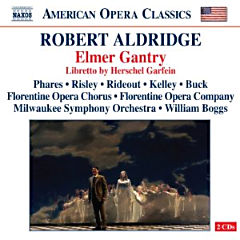

by Robert Aldridge with a libretto by Herschel Garfein.

The work has had a modest success after a premiere at Nashville Opera in 2007 and several collegiate performances. The recording under consideration here emanates from the opera’s second professional production at Florentine Opera in 2010.

Aldridge charts the obvious path with a score full of Copland-like Americana and by exploiting the natural place that hymn tunes (all newly composed except for a reference to “What a friend we have in Jesus”) have in the pageantry of the revivalist service. When the characters are in a more reflective or sensuous state of mind, the composer generally captures the moment deftly and with a rich orchestral palette. There is no new ground broken here, but the music generally suits the mood and dramatic purpose, remaining melodic with a bit of dissonance thrown in for effect.

Although the novel is the model, the opera owes a lot to the movie with its cinematic sweep. The difficulty is that the natural pace of an opera is slower than a film and as a result attempts to give each character in this big cast an aria end up short-changing an important focus on the two leading players. Why for example does the first act end with a patter/laughing aria for Eddie Fisslinger, which, while audibly appreciated by the audience, ends up leading nowhere dramatically?

The second act is more successful than the first, which is full of cursory attempts to introduce the large cast and set the scene. In the second the creators are able to dig more deeply into the characters and understand what makes them tick. More time is spent with the protagonists, ultimately creating more satisfying connection with the drama and effectively setting up the work’s denouement.

The performance is generally acceptable although a stronger cast would have made it even more persuasive. Most successful is Keith Phares as Elmer Gantry. The role is a true tour de force and while a burlier sound might better suit the role of the football player turned preacher, Phares sings with great commitment and security.

Unfortunately Patricia Risley, however committed her performance, lacks the richness of voice and charisma to make Sharon Falconer live. There is an occluded quality to her middle voice, where much of this role lies so while she is effective in the soft lyrical passages, sensuousness of the role eludes her. The role was intended for and written for Lorraine Hunt Lieberson and one’s thoughts turn to what she would have made of it had she lived to perform it.

Vale Rideout is effective as Elmer’s friend Frank, whose second act aria is one of the highlights of the score even if you are not sure why it is there. The rest of the cast is pretty variable. Heather Buck doesn’t really make much of an impression as Lulu Baines and while the audience enjoys Frank Kelley’s rendition of Eddie’s laughing song, it is vocalized with a wavering, reedy sound that doesn’t make it musically satisfying. The lower men’s voices (Jamie Offenbach as T.J. Rigg and Matthew Lau as Reverend Arthur Baines) are hampered by vocal writing that places much of their roles in an extremely awkward and unflattering register.

The orchestra led by William Hobbs Boggs, plays effectively and the chorus is enthusiastic if occasionally tentative.

The question with every new work is will this have a life going forward? The musical style is accessible and (in the hymns) even “catchy” and the number of roles and disposition of them make this an attractive collegiate offering. On the other hand dramatically there is still some loose ends.

Time of course will tell whether it will find a wider audience. But after listening to this recording, I’d be encouraged to hear Aldridge’s next work.