Robert Schumann said he devoted more love and energy to Manfred than any of his other compositions. It took him only about a month in 1848 to adapt a translation of Byron’s semi-autobiographical poem about a guilt-ridden noble into a program consisting of an overture and 15 pieces for chorus, orchestra and spoken voice. Schumann was pleased enough with the result that he told Franz Liszt, who conducted the premiere, the piece was unique and couldn’t be categorized an opera, melodrama or Singspiel.

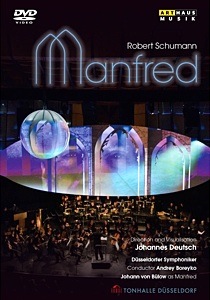

The composer couldn’t have known it, but his exploration of the psyche and the work’s episodic narration might have made good fodder for an art film. The Austrian media artist Johannes Deutsch sensed these cinematic possibilities when he conceived a rare production in Dusseldorf last year for observances of Schumann’s bicentennial—a live performance of which is now available on Arthaus Musik.

The oft-stated knock on Schumann is that his dramatic compositions tend to lack strong narrative threads and forceful vision. While that may be the case with Scenes from Goethe’s Faust or his only opera, Genoveva, Manfred has well-defined characters and vivid depictions of personal strife. One problem, at least for a non-German audience, may lie in the prominent use of spoken text recited over a musical accompaniment. This approach keeps the plot moving but also locks the protagonist and other characters in lengthy monologues or exchanges lifted from a translation by Karl Adolf Suckow. Another issue is the technical challenge of staging a tale filled with sorcery, apparitions and lots of existential angst against the backdrop of the Alps.

Deutsch tries to put the audience in Manfred’s shoes by superimposing close-ups of the title character (Johann von Bulow) on panoramic scenes and projecting hallucinatory shapes and colors on a suspended sphere and an eye-shaped screen behind the orchestra. Converting the auditorium into the kind of “mental theater” Byron envisioned was inspired, especially given the design of Dusseldorf’s Tonhalle, a circular, domed building originally designed as a planetarium. Deutsch’s images fairly pop out on DVD, even though some shots are quite dark and a bit blurry around the edges and in the foreground.

Though Schumann uses fragments of melodies to effectively conjure dream-like settings, Manfred‘s music doesn’t quite amplify the drama in the way Berlioz or Wagner might. These are, by and large, delicate pieces intended to blend into the rhythms of the language, not underline inner conflicts or the title character’s rejection of authority. The opening “Gesang der Geister” is a charming ensemble piece set against a triplet pattern in the strings. Schumann’s penchant for bold melodies emerges in sections like the `”Hymnus der Geister Arimans” midway through the piece. The most effective vocal writing may come in the serene closing scene, a Requiem that follows Manfred’s rejection of an abbott’s blessings and his declaration “It is not so difficult to die.”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FXDD1Yi0yck

Like Beethoven’s Egmont, Manfred is almost entirely known these days for its overture. Andrey Boreyko and the Dusseldorf Symphony Orchestra deliver an energetic reading to start the evening off and generally deliver nicely scaled accompaniments in the entr’actes and short scenes. Von Bulow fully inhabits the title role, relating his tormented visions and longing for his lost love, Astarte, in flowing lines and hushed whispers. Soprano Mechthild Bach, mezzo Elisabeth Popien, tenor Hans-Jorg Mammel, and basses Markus Flang, Manfred Bittner, Ekkerhard Abele and Tobias Berndt acquit themselves well in the musical interludes.

All in all, the staging makes perhaps the most convincing case possible for a dramatically unwieldy work with some archaic forms. Though it wouldn’t be as riveting without all the eye candy, Manfred proves itself more than a charming relic of the early Romantic period and something less than a forgotten masterpiece.