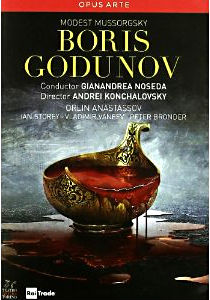

In the fall of 2010, director Andrei Konchalovsky and conductor Gianandrea Noseda struck up a collaboration for a new production of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, to be performed at Teatro Regio Torino, co-produced with Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia of Valencia and Fondazione Lirico Sinfonica Petruzzelli e Teatri di Bari.

The adaptation seeks to return to the 1869 version that Mussorgsky “instinctually” wrote, rather than the revised version of 1872, viewed here as an attempt to assuage the opera committee of the Marinsky Theatre that had rejected the original version. Noseda and Konchalovsky make clear that they believe the 1869 version to be closer to the composer’s original intent and thrust; they see the 1872 version to be “cleaned up” and romanticized with the addition of the Polish Act. The only part of the later revision used here is the Kromy Forest scene, here inserted prior to Boris’ death scene. This version ends with the death of Boris and a reprise of the Holy Fool’s lament.

Konchalovsky and Noseda’s committed efforts have provided a decidedly mixed result on this DVD version released by Opus Arte. The vital political drama of Boris and his relation to his subjects is grimly, violently clear; perhaps never has Boris’ and the people’s mutual terror of each other been so clear.

But, as in Buchner’s unfinished play Woyzeck, there is an odd sense of disconnection between the eight scenes presented. This version sometimes feels like a scene from eight different operas stitched together rather loosely. Noseda and Konchalovsky make the point that there simply is no “definitive version” of Boris; they attempt to present the opera as they believe Mussorgsky originally intended it.

The production is stark and minimalist with little furniture and less specificity of location—Konchalsky’s lighting provides the majority of scenic effect. The costumes are standard-unhappy-peasant. The singing is generally fine, with standout performances from Vladimir Vaneev as a haunting Pimen and the wonderful Holy Fool of Evgeny Akimov, who gives his character an astonishing wisdom in his seemingly crazed utterances.

Ian Storey seems oddly detached and uninteresting in the pivotal role of Grigory, who becomes pretender to the throne after learning of Boris’ likely role in the murder of the previous tsarevich. Vladimir Matorin as Varlaam and Luca Casalin as Missail are working waaaay too hard at being the “comic relief” as the drunken monks in the Inn Scene; they might be reminded that less can be more. Peter Bronder is a stalwart Prince Shiusky, though he, too, seems over-demonstrative; he is “acting out” instead of acting.

The vital chorus work of this opera (in no other opera is “the people” such an essential element) is vocally resplendent. They sound simply wonderful, with clear diction and a sound that thrills and moves. But, alas, they are undercut by the direction of their physical movement. In the opening scene, they are evidently directed to do unison movements more reminiscent of a college football cheering section than a crowd looking toward a new Tsar. Literally, they begin by doing what appears to be “the wave.”

Later, Nikitich leads them in movements very much like calisthenics. The effect is ridiculous, and completely undercuts the importance of the scene. Unfortunately, the chorus continues throughout to be asked to perform unison movements that simply don’t work. In some chorister closeups, you can almost see them wishing they could just sing!

Also vocally elegant and potent is the Boris of Orlin Anastassov. A little grainy and underpowered in his first scene, he steadily grows into a harrowing death scene. But again, his efforts are undercut by acting/ directing (?) choices. The biggest error here is that Boris seems unhinged from the get-go, even in the coronation scene. The poor man thus has nowhere to go with the rest of the opera except to become over-the-top unhinged.

Anastassov is also done in by eye makeup of the Cruella DeVil/Caligula variety and a tendency to use eye-bulging far too much to convey the sense of madness. I have a strong sense that hearing a CD of this Boris might be an entirely different (and more positive) experience.

It should probably be mentioned that this DVD presents the longest curtain call that I think I’ve ever seen. Virtually everyone in the huge cast is given an individual bow, and the audience is noticeably tiring by the time the major characters make their appearance. They do rouse themselves finally for a sizeable ovation for Anastassov, but the group bows at the end are greeted with flagging enthusiasm.

The DVD also contains interviews with the creative team, in which Noseda seems quite clear about the ideas of this version of Boris; the interview with Kolchansky reveals a very muddled and platitude-imbued thought process. For me, this is reflected in the performance; Noseda leads a musical experience of clarity, flow, and power; the stage direction is inconsistent and full of “effects” that don’t serve the storytelling.

Boris may be many things, but he must not be one-dimensional “crazy” as he is here. It seems to me that this adaptation could be a very sound way of approaching Boris Godunov, but it somehow goes awry between conception and the stage. It is a noble effort that doesn’t quite work.