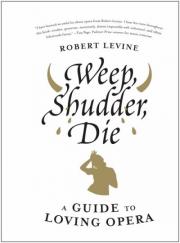

Classical music writer and opera critic Robert Levine has written a very pleasant new book

, Weep, Shudder, Die, A Guide to Loving Opera, published by HarperCollins Books. Levine sets up the book’s premise early in his introduction: “Could singing… make one, as the composer Vincenzo Bellini said, ‘weep, shudder, die’ and at the same time entertain, warm, and fill with joy?”

While the book claims to be a “guide to the grand art of opera for both new and longtime fans”, it is clearly aimed at those new to opera or those with an early budding interest. It is these groups that will find pleasure in Levine’s work; however, those with lots of opera experience will find few new insights here.

Taken as a whole, Weep, Shudder, Die is a reader-friendly, breezily written primer to the world of opera. Levine’s greatest strength is his palpable passion and enthusiasm for opera and, in fact, all forms of singing. His love and delight in the form is infectious. In the book’s charming Introduction, Levine tells of his slowly developing childhood interest in opera, starting with pop music (The Platters, Anka, Holly, Orbison), then moving to Miss America contestants singing arias, followed by a sudden love for the voice of Mario Lanza.

Finally introduced to recordings of Bjorling in Pagliacci and Callas in Lucia, young Levine was hooked. It’s a familiar journey for many opera lovers of his generation. Here is an almost ecstatic statement that ends the Introduction:

I have, since then, been loyally obsessed with the operatic voice. There’s something so freakishly glorious about it, from bass to high soprano, that it demands a visceral reaction—anger, sadness, empathy, elation—and instant metaphor: dark, light, velvety, silvery, bell-like, chocolate, warm, golden, icy, laserlike, smooth…To this day, I cannot understand why people don’t sing—opera and otherwise—all the time.

This statement is operatic in itself.

Levine then sets about to demystify the world of opera, dismissing those who find it stuffy or remote. The breezy tone continues through a brief précis on the history of opera from Monteverdi to YouTube and a discussion of why people still shy away from opera with headings such as “Everybody sings all the time and that’s not the way life is” through “The Plot Does Not Really Matter, Parts I, II, and III.” After touching on Regietheatre and the need to have libretto in hand when listening to CD’s, we arrive at the meat of the book: a brief précis of 50 major operas.

There is no in-depth analysis to be found here. Each opera is given a short paragraph or two about the composer, a “Who’s Who” of the major characters, a “What’s Happening” section with a very brief synopsis, and Levine’s choices of “To Die For Moments” in the score.

There are sections on German Opera, Mozart’s Operas, Opera in English, Italian Opera, French Opera, and Russian Opera and, while some of Levine’s choices might be a bit questionable, he covers all the standard repertoire. While the writing remains light and sometimes humorous, Levine begins inserting some strong and questionable opinions in this section, and makes several odd factual errors.

An example of an opinion presented as fact which many (including this reviewer) would object to can be found on page 84: “Though some operas by even the greatest composers—Verdi, Puccini, Wagner—can afford to be cut a bit here and there, Mozart’s operas are so perfect that each note counts.” Many an opera lover would be inclined to do a “spit-take” after reading that statement. Sometimes, the synopses are absurdly abbreviated—Act Two of Rigoletto gets one sentence: “Rigoletto realizes what has happened and swears revenge.” (I could swear that Gilda has some involvement here!)

There are several highly questionable statements as well. In the synopsis of the last act of Trovatore, Levine states “…and when Leonora enters and is accused by Manrico of giving in to the count’s dirty advances, she poisons herself.” Well, not really, and this is corrected on the following page!

Act II of Traviata: “Even though she knows she suffers from consumption and that leaving Alfredo will only make her worse, she returns to Paris and takes up with Douphol.” (takes up with him??)

Aida: “Act III opens on a secluded bank of the Nile, where Aida waits to fret and whine with Radames.” (???)

About Otello: “Eliminating the Bard’s entire first act, the action begins and ends in Cyprus; Desdemona’s father, the duke, and Brabantio are also excised.” (But Mr. Levine, Desdemona’s father is Brabantio!)

And finally, the end of La Gioconda: “Barnaba arrives to have his way with Gioconda, and she manages to sing girlish coloratura around him before she drops dead. Priceless.” (No mention of the fact that she stabs herself before “dropping dead.”)

Some of this may have been worded to make humorous points, but I found these and other statements rather grating. The book’s primary audience of newcomers will likely not notice any of these odd moments, however. On the whole, Levine writes with real humanity, grace and charm. I would recommend this book as a gift for anyone’s opera newbie friends. It’s an easy read.