Better remembered, perhaps, for his skillful setting of word game songs like “I Am the Captain of the Pinafore” and “When I Was a Lad,” Sullivan was a dab hand at anthems (such as “Onward, Christian Soldiers”) and set Gilbert’s parody of inane jingo, “He Is an Englishman” so perfectly that its outrageous anti-patriotic sentiments often go quite unnoticed by audiences, and his Mozartean extended finales (Act I of Pinafore, notably—but also those of Patience, Iolanthe, The Mikado, Yeomen of the Guard), in which melody leads to melody leads to melody, form evolving from duet to solo to chorus to trio to solo to chorus (for example), without a break and without the least slackening of plot tension—and they’re terrific tunes delicately harmonized, to boot!—is a beautiful, seamless thing, a lesson unlearned by far too many of his successors on the musical stage. (The Gershwins attempted a show in the heartless G&S manner: Of Thee I Sing, and it won them a Pulitzer.)

The G&S oeuvre remains well-known and well-remembered, though no longer central to our culture. Too, since voices are seldom trained now except for opera, and G&S producers always insist that the Savoy operas are not opera—they aren’t, but Sullivan wrote for well-trained voices—you rarely hear this music done justice to. Gilbert insisted on actors who could sing rather than singers who could act as the right mix for his shows, and he was right; but untrained or strained voices kill them as thoroughly as grand opera excess can.

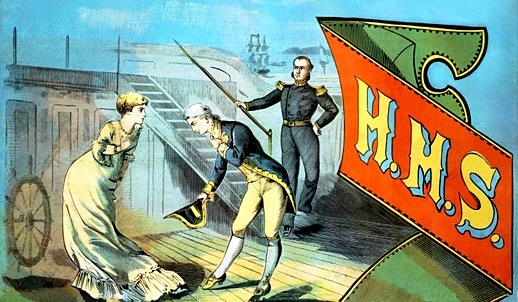

Will Crutchfield of the Caramoor Festival’s bel canto program, having a young artist and apprentice program to deploy, came up with a happy compromise for the opening night of this year’s festival, a semi-staged HMS Pinafore. The weather cooperated (not too warm, not too sprinkly), the gala audience proved summery and soignée, and the elegant formal gardens could not have looked or felt more hospitable. One did regret, now and then, being unable to leap into the refreshing blue sea projected behind the columns of Caramoor’s Venetian Theater.

Gilbert was renowned in his time for the revolution he made in the professionalism of staging, and the D’Oyly Carte company froze those traditions in aspic. Today a light semi-staging like this one, with singers and chorus who can play the lines and toss a few coordinated dance steps into their performance, can be delicious, though a “naïve” Josephine who shakes her breasts in our face at every dancy rhythm would have got her fingers sharply rapped—if nothing else—by Sir William. In Gilbert’s unreal world, to be too “knowing,” to wink or nod, is to undercut the superbly logical illogic.

Take the foolish to extremes by all means, but the characters must believe in themselves, believe that they are sincere and making sense. In Gilbert’s ridiculous plot, two babies are switched in infancy, neither family catching wise, who now find themselves somehow twenty years apart in age (and rank). If one of them (as at Caramoor) was black, the other white, the story is not the least bit sillier than it already was—rather, the daffiness is deliriously compounded! No one, of course, remarks on it. Gilbert would have loved this. (Though Mark Twain had already done it this way, in Puddin’head Wilson.)

Most of the Caramoor performers played their characters straight, which is the funniest way to play them. Excess mugging is death to wit, and Gilbert’s deadpans about the glories of bureaucratic government and the egotism of its practitioners are as spot-on as they ever were. Jason Plourde played Sir Joseph with a fixed, official grin, but he didn’t wiggle his brows unnecessarily to signal a joke—and when he did lose his cool, how terrible the aspect of his eyes! (Too bad Gilbert kept Sir Joseph’s hornpipe offstage.) Jorell Williams performed the Captain with a pleasing baritone and a touching faith in his role as role-model, and his social position, whether high or brought low.

Robert McPherson, his alter baby ego, a tenor of some operatic experience, molded Ralph’s high lyric lines with the tenderness they deserve and raced through the insane foolery of the sailor’s “simple eloquence,” each mad simile sharp and clear. Scott Bearden was fat rather than “triangular” as Dick Deadeye, but he took great malicious delight in being the show’s ambassador from the real world. Difficult to believe he was not converted to optimism, as anyone else would be, by the gorgeous silly madrigal, “A British Tar Is a Soaring Soul,” deliciously warbled by Mr. McPherson with Nicholas Masters and Jeffrey Beruan.

Georgia Jarman was not so felicitous as Josephine. It’s not an easy role, with a lovesick ballad in Act I, a raging duet to kick off the endless finaletto, and a major coloratura showpiece (sending up everything from Donizetti to Meyerbeer) in Act II. Besides her excessively brassy unmaidenly wiggles (and a platinum wig only encourages such tendencies), she has an uneven voice, full in the lower ranges but uncertain of pitch and ornament on Sullivan’s less than stratospheric top. She milked it; I would have liked her better if she’d simply played it cool and low-key: Just sing the notes.

Vanessa Cariddi made an incongruous Buttercup, taller and slimmer and far sexier than she is generally played, but somehow living the ditziness of this urbanized Azucena. (Does Pinafore rhyme with Trovatore?) I liked her over-the-toppiness, but I kept thinking Phoebe Merrill or Mad Margaret might be more her zany speed, and she has the vocal chops for those parts. Tynan Davis sang a Cousin Hebe of more than usual personality.

Diction was excellent all night, not least from the chorus drawn from the Young Artist and Apprentice programs. You can get away with fudging Sullivan’s musical lines, though it was a tremendous pleasure for once to attend a Pinafore in which he was given his proper due, tenor and all, but you can’t present Gilbert, fudging the words, and achieve anything worthwhile. Mr. Crutchfield and his crew understood that perfectly.

In the afternoon before the concert, the Young Artist and Apprentice programs gave, as they usually do, a couple of concerts in the Spanish courtyard of music apropos the major offering. Arias from English operas before Sullivan (Purcell, Boyce, Benedict, Balfe) were of interest, but the youthful voices in the program had difficulties with such mature fare as Weber’s Oberon, Arne’s Artaxerxes and Sullivan’s own Ivanhoe.

A program of concert songs, often with nautical motifs also divided between immature voices and thrilling ones. Jessica Lennick sang “A Sailor’s Song,” and the melody had such charm I couldn’t imagine how the composer had escaped fame, and checked the program: Franz Joseph Haydn, during his London visit. Oh. Rolando Sanz sang “The Death of Nelson” with a most promising well-supported tenor and bass Nicholas Masters displayed some impressive low notes in “The Mighty Deep,” while Emmett O’Hanlon’s attractive baritone took on “The Lass that Loves a Sailor,” the popular air that gave Gilbert his alternate title for Pinafore. Anthony Webb and a chorus sang “Rule Britannia” from Arne’s opera, Alfred, but the audience, inexplicably, did not join in the final couplet. They always do at the Proms!

Caramoor audiences love to have their sophistication tested (and to pass the test), so there were two encore items, Victorian sea chanteys (watch that soft “ch”! Crutchfield got it right—no more excuses for the rest of us) of dubious color. “The Backside Rules the Navy” seemed appropriate for the day gay marriage passed into law:

“If you want a bit of bum

Better get it from your chum;

Ye’ll get no bum from me.”

Caramoor’s major operatic offering of the summer, on July 9 and again July 15, will be Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, with a starry cast featuring Julianna Di Giacomo, Michael Spyres and Daniel Mobbs. Remember: The apple is a target, the arrow the projectile.