A gaggle of scruffy university types approaches the dispersing crowd from the opposite end of the expanse. “Let’s make a deal,” Europe’s Contemporary Atonalists suggest to the opera-goers. “If you hang with us through our throbbing tone clusters and the like, we’ll give you some good old traditional Greek drama. Deal?” Then a bevy of opera administrators commences inking up contracts.

An apocryphal scenario, quite obviously—though, within the last few years, a body of new work has emerged as though in direct response to such an event. James Dillon’s 2004 entry into the world of music theater, Philomela, worked from narrative shards passed down from Sophocles. Then Harrison Birtwistle brought his take on The Minotaur to the Royal Opera House in 2008 (and to an OpusArte DVD not long afterward). Meantime, in what he swore would be his last opera—before un-retiring once again last year—Hans Werner Henze completed a stage work in 2007 based on the myth of Phaedra.

Borrowing from the Greek narrative store is hardly a new move. Yet this particular trilogy of works—which encompasses a mid-career PhD from the modernist academy (Dillon), a tenured department chair (Birtwistle) and its president emeritus (Henze)—remains noteworthy. Their collective reliance on ancient dramatis personae could even be looked at as a hedge against anti-modernist suspicions – that all this new-ish sounding music (or rather, “new” to any listeners unmoved by innovations of the prior century) is at least rooted in dramatic structures of longer standing reputation.

While such a calculation would be an understandable move, it is not, on its own, one that guarantees substantive success. Birtwistle’s Minotaur is enjoyable enough as it goes along in its aggressively varied orchestration – though it labors a bit excessively before getting to its climactic twist of a humanized Minotaur capable of speech (if only in its own dreams).

Dillon’s use of Greek myth is more innovative throughout, since the title character winds up having her tongue cut out. (The composer also juggles the chronology in a manner akin to art film storytelling.) But Dillon’s demotion of traditional operatic voice technique isn’t likely to win many converts, or productions; I’d be surprised if we ever saw a staging in America.

In this sense, Henze’s Phaedra has already won the transcontinental contest by default, in that it has survived its European premiere and is currently seeing its US premiere in Philadelphia. But Phaedra also impresses on the merits: at under 90 minutes, it’s the most compact of the recent modernist Greek glosses, while managing to be the most emotionally varied work out of the three. It’s a compliment to say that the music, while not full of surprises, is much as you’d expect from Henze in his grand, late period: a clattering ride through fields of modernist dissonance interrupted briefly by pauses taken at the border of a neighboring Mozartean meadow.

The narrative ride here feels appropriately madcap, as well. Though the opera’s first act goes after a traditional recounting of the Phaedra story—in which Theseus’s second wife, on the advice of Aphrodite, falsely cries rape once her advances on the stepson Hippolyt go nowhere—Henze and librettist Christian Lehnert use their short second act to go expressively gonzo.

By evoking a science fiction-style reanimation for multiple characters who have already met some mortal end, Henze’s score suggests that, quite aside from being rocked by fate, each individual will take a turn at the mercy of ambient, ill-advised influences—and then need to reconstruct his or her own identity anew. (A clue here rests in a vocal trill associated with Phaedra through most of the opera, but which is passed around in the final chorus to other characters.)

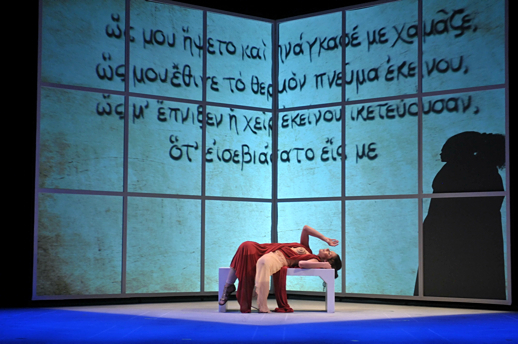

The spare production designed by Phillipe Amand for the Opera Company of Philadelphia’s “Perelman” series of chamber works gets the job done economically without coming across as anything close to cheap. (Only a few over-literal video animations – of bird wings in flight and a severed arm being blown off of a statue — are unintentional smirk-bait.) In what might slay any viewer of the first half of the Met’s latest Ring cycle, this production shows how a hinged, multi-part moveable scrim for rear-projection and video images can be lightweight, unobtrustive, drama-enhancing and next-to-silent while weighing closer to 45 pounds than 45 tons.

Another huge plus is that mezzo-soprano Tamara Mumford, a Lindemann program graduate, has been cast in the title role and not some supporting bit, since she dominates this production whenever she is onstage. During Sunday’s matinee performance, Mumford proved capable of threading interpretive nuance through music sitting in any register. While disrobing in the sleeping presence of her soon-to-be horrified stepson, her mid-range danced with convincing desire while avoiding the wide-open trap door into some over-dark parody of doomed lust; her character’s significant (and exciting) risk-taking was always apparent instead of assumed. Similarly, in passages during the second act—when the re-animated Hippolyt sits in cage designed for his own benefit by Artemis—Mumford put a lyric charge into Henze’s teasing, weird high notes: a recognition that sadness and regret often sit within the most elaborate harassments.

The libretto seems to ask for Hippolyt to articulate a fragmented, uncertain identity in the second act more or less equal in complexity to Phaedra’s in the first. Though William Burden’s tenor was pleasing throughout, he couldn’t quite match Mumford at this level of actorly nuance. (Though it’s possible, going back to the Manon character in Boulevard Solitude, that Henze saves some of his juiciest parts for women. Discuss!)

At any rate, I wanted Hippolyt to seem transformed in some way by his rebirth and renaming at the hands of Artemis, but by the opera’s close he still seemed like a slightly incurious if confused young boy—even as his lines adopted Phaedra’s opening metaphorical obsession with bird-flight and travel. It is up to a late-appearing, non-monstrous Minotaur, sung by Jeremy Milner, to take up some of this narrative slack.

Soprano Elizabeth Reiter, playing Aphrodite, and countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo, playing Artemis (the only focus of Hippolyt’s affections, wink-wink!), both delivered successful supporting performances. Henze’s writing for the latter role revealed a range beyond even the one required by Ligeti’s Prince Go-Go, which Costanzo sang in the NY Philharmonic’s production of Le Grand Macabre last season. The ensemble playing from the Philadelphia Opera’s chamber forces, as led by conductor Corrado Rovaris, sounded crisp and up to the level of a reference CD of the European premiere provided by Henze’s publisher.

All of these attributes, when filtered through the mostly clear direction by Robert Driver, add up to a compelling reason to take a trip to Philadelphia before the end of this production’s run this weekend. If you love modern music, there’s absolutely no reason not to go. If you remain suspicious of new works but are constitutionally willing to be persuaded, I’d recommend you bypass the Birtwistles and Dillons of the modern Euroscape and let Henze try to talk you into a dark but thrilling new sort of affection. The good news is that, if hooked, you’ll soon have another fix; next year Henze’s Elegy for Young Lovers will be offered by Curtis Opera Theatre as part of the Opera Company of Philadelphia season.

(Photos by Kelly & Massa Photography)