In the process of unearthing forgotten musical works, sometimes we stumble across a gem. World War II saw an entire generation of European composers forced into internment or diaspora, and their works are only slowly being rescued from obscurity.

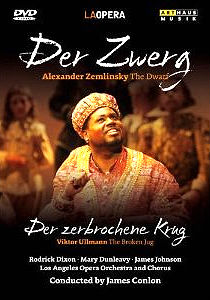

In a recent DVD release from the LA Opera, a part their Recovered Voices series, we are treated to a double bill of short operas by Viktor Ullmann and Alexander Zemlinsky, two composers unjustly thrust aside by the rise of fascism. James Conlon conducts both with great tenderness and care, explaining his commitment to the works in an accompanying essay.

Ullmann composed Der Zerbrochene Krug in during a period of great political and personal uncertainty, only shortly before his deportation to Theresienstadt (he would be killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944). The tone is remarkably light and funny, but explicitly satires the hypocrisy of authority. He takes his libretto from a play by Heinrich von Kleist, condensing the action into one act. Darko Tresnjak’s production begins with a shadow play depicting the demise of the jug, giving the audience the facts to the legal comedy to follow.

The curtain rises on a sleepy Dutch village, a pastel-colored confection of windmills by Ralph Funicello. A hard-partying judge (James Johnson) wakes up wigless and in need of a mimosa, but is rushed to court where an insistent widow (Elizabeth Bishop) demands justice for her broken jug – an awkward double entendre in the subtitles. After a bit of courtroom confusion, the culprit turns out to be the Judge, who had been drunkenly chasing after the widow’s sexy daughter (Melody Moore).

The work comes across as a lively start to the evening, yet not particularly memorable. The culprit here is not the charming production nor the witty music, but an overly efficient libretto that treats the characters as cogs in the wheels of the plot. As a result, nobody in the ensemble cast has much of an opportunity to stand out, and we are left waiting for the main course to arrive.

The second offering on the DVD, Der Zwerg, is happily more substantial. Zemlinksy was an important musical figure in Europe before the rise of fascism; after immigrating to the United States to avoid Nazi persecution, he died in complete obscurity. His orchestral music has gradually regained deserved attention, but his operas remain relatively neglected. From the first notes, the score drips with post-romantic passion and longing – something like the harmonies of Strauss with the accessibility of Rachmaninov, colored with Germanic touches of sunny Spain. George Klaren’s libretto compresses the action into one scene, wisely eliminating the talking animals that pervade much of the Oscar Wilde source material, “The Birthday of the Infanta.”

On the morning of her birthday, the Infanta (Mary Dunleavy) gleefully peeks through the loot she is going to receive. But the best gift of all is a dwarf (Rodrick Dixon), who promptly falls in love with the princess. Despite the pleas of her maid Ghita (Susan B. Anthony), the Infanta decides that the Dwarf should see his own reflection – he has always lived with the illusion that he is extremely handsome. When the poor dwarf finally sees himself in a mirror, it breaks his heart and he dies.

The Infanta of the short story is a neglected girl stuck in a gloomy castle, but the opera develops her closer to Wilde’s notorious mean girl, Salomé. Dunleavy looks every bit the powerpuff (in some Shirley Templesque creations by Linda Cho) but packs a mean punch. An athletic vocalist, she hops up and down the staff without ruffling her petticoats, and lets the long phrases drip with just a touch of sweetness. Conlon writes that the role was based on Zemlinsky’s affair with a student named Alma Schindler, who had left him years earlier for Gustav Mahler. The role is hardly sympathetic, and as in her recent triumph in City Opera’s Intermezzo, Dunleavy is able to create a complex portrait of a flawed human.

Zemlinsky identified strongly with the Dwarf, both physically and emotionally. While Wilde wrote the character as a rather standard holy fool, the opera envisions him as the focal point of the action, crafting an Oedipal hero that is destroyed when he discovers his own flaws. Dixon brings a supple voice that is able to carry over the dense orchestration; this is someone to watch out for. He creates the visual illusion of the deformed body, but more importantly, he conveys the universal insecurity of seeing our faults magnified.

Tresnjak uses Velasquez’s “Las Meninas” as inspiration (as did Wilde for the story), giving us an attractive if traditional production. He handles the chorus with a deft touch, shaping them into some lovely tableaux. But most importantly, he wisely minimizes his regie, allowing the cast to find the characters already written in Zemlinsky’s score.

Comments