When Hans Von Bülow joked that Rienzi was Meyerbeer’s best opera, he was not very far off the mark. In fact, Rienzi, der Letze der Tribunen, Wagner’s third opera, has all the traits of a typical “grand opéra”: it is divided in five acts, features a historical character or situation, makes large use of the chorus, and includes a ballet.

If Wagner had been granted his wish, it would have even been sung in French, as the composer tried all he could to have it premiered in Paris. Only when he realized this would never happen, he turned to King Frederick Augustus of Saxony, and managed to have it produced in Dresden.

Although Rienzi was greeted with rapturous enthusiasm, Wagner quickly repudiated it. Nevertheless, in Germanophone countries it remained one of Wagner’s most popular operas all throughout the 19th and well into the 20th century, the number of its performances dramatically dwindling only after War World Two.

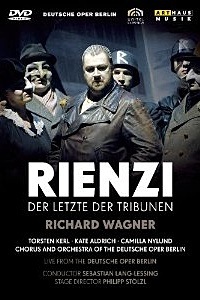

The DVD under review presents a production from Deutsche Oper Berlin, performed in April of this year.

I am not sure whether to call it a selection, or highlights from Rienzi, considering that only approximately half of the opera is performed. Rienzi is Wagner’s longest work, clocking at almost five hours; the Dresden premiere lasted six hours including intermissions. With an opera of such exorbitant length, cuts have always been inevitable. Wagner himself excised several pieces for the second performance, to the chagrin of the singers, who wanted to perform all the music they had taken so much trouble to memorize. The composer then split the opera into two consecutive evenings, but the audience did not appreciate paying twice for the same opera, so Wagner’s final solution was to perform the whole work in the same evening with some cuts.

If he used the scissors, the Berlin production team resorts to the ax, expunging about two and a half hours. The original first and fifth acts are largely kept intact. The second, third and fourth acts are reduced to stumps. Entire scenes are deleted, and inner cuts abound. The “new” edition is divided into two parts, respectively reflecting Rienzi’s rise and fall.

Nicola di Lorenzo, better known as Cola di Rienzo or simply Rienzi, was a mid 14th century Roman populist figure who, taking advantage of Rome’s political chaos and the fact that the Papacy had been removed to Avignon, managed to seize power from the aristocracy, granting wider rights to the common people. His fortune went on through ebbs and flows and his life was worthy of an adventure novel, through triumphs, captivity, a death sentence, and several escapes. After managing to gain power one last time and proclaiming himself senator, he ultimately fell of favor with everyone and even the commoners turned against him, setting fire to the Capitol where he had taken shelter, and was stabbed to death while trying to escape in disguise.

The early 19th century re-discovered the figure of Cola di Rienzo. His having fought against the aristocracy, his attempts at unifying Italy and minimizing the Papal power made him a tragic hero in the eyes of liberal nationalists. Wagner himself, who in his youth was what nowadays would be called a progressive, dreaming of a unified Germany, fell in love with Rienzi after reading Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s eponymous novel.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI93cCE6vP4

Stage director Philipp Stölz, who started his career directing video clips for (among others) Madonna, is unable to resist the temptation to view Rienzi’s life and career through the lens of the dictatorships of the 20th century. There is a definite link between the opera and this period: Stalin used to have the overture played during his military parades, and Hitler’s worship of this score is well known. It was his favorite opera, and he owned the manuscript, which most likely was destroyed in his bunker the day of his death.

However, the concept is already drab and platitudinous, almost obvious; Nicholas Hytner had already used it almost two decades for a production of Rienzi at ENO.

Stolz sets the action in the late 1930s, and his protagonist is a cross of Mussolini, Hitler and perhaps Stalin, or, better, a caricature of them. More often than not, Stolz’ dictator is evocative of Charlie Chaplin’s Hynkel. His Rienzi has very little, if anything, in common with the tragic hero imagined by Bulwer-Lytton and Wagner; with bulging eyes, he thrusts his jaw forward in pure Mussolini style. During the overture, a corpulent Rienzi’s stand-in plays with a globe and does somersaults and cartwheels. The Roman people are first represented as grotesque clowns; only after accepting Rienzi’s leadership do they change into black dresses with white aprons (for the women) and into Nazi-style uniforms (the men).

Irene, Rienzi’s sister, undergoes a similar transformation. Wagner’s ingénue becomes a Über-Frau, a sort of a blend between two famous Evas (Braun and Peron) with a touch of Ukraine’s Yulija Timoshenko with her characteristic halo of blond braids. Stölz not too timidly suggests an incestuous relationship between the two siblings, a very Wagnerian theme indeed.

Whenever Rienzi appears on stage, his face is projected on a large screen, so as to suggest that all his life is nothing but a huge photo-op. Stölz also makes ample use of films reminiscent of the old propaganda newsreels.

The ending has been modified as well. Whereas in the original opera Rienzi, Irene and Adriano all die under the collapsing Capitol, in Stölz’ version Rienzi is first stabbed by Adriano and later finished off by the mob, Irene is murdered in the bunker, while Adriano is allowed to survive.

Although Stölz’ approach may be debatable, it is undeniable that he succeeds in bringing to life something extremely theatrical, creative and of secure impact on the audience. I may take exception with his perception and portrayal of Rienzi, but I never got bored.

Sebastian Lang-Lessing conducts with vigor and brilliancy, drawing a glorious sound from the Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper. In this opera the chorus is the co-protagonist and Rienzi’s principal interlocutor, and the contribution of the Deutsche Oper Chorus is simply magnificent.

Helden-tenor Torsten Kerl is impressive for his stamina. Rienzi’s role, even in this abridged version, is of monumental arduousness, relentlessly hitting the area of the passaggio and above; Kerl makes it to the end of the performance with no sign of strain due to a iron-clad technique.

Irene is not a memorable part; Wagner did not assign her an aria. This production has Irene often on stage, a first lady to her brother, even when she is not singing. Camilla Nylund brings to the role a fine stage presence, good acting skills but an undistinguished lyric soprano.

Kate Aldrich sings the role of Adriano Colonna, a part created by Wagner’s favorite soprano and muse, the legendary and scandalous Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. Aldrich does not play Adriano as a hero, but rather as an insecure, unconfident young man emasculated by his father’s domination. She has one of those “amphibious” voices that stretch the border between soprano and mezzo-soprano, and therefore a good fit for this ambiguous role. Her instrument, though not large, is pleasing and homogeneous throughout its range. The Berlin audience seems to love her and bestows on her the biggest ovation of the evening.

This production demonstrates that, with all his flaws and weaknesses, Rienzi is an enjoyable work worthy of more frequent appearances. Who knows, perhaps one day Bayreuth will accept the challenge. One would hope so, especially considering that it was Cosima – and not the composer himself, who banned this opera from that holy stage.