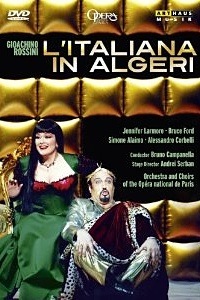

Halfway through the overture to L’italiana in Algeri a pin-up cartoon of our Isabella, Jennifer Larmore, slowly slides up and down a pole, setting the tone for the whole opera.

Cartoonish is indeed the first adjective that springs to my mind when trying to describe this 1998 production of Rossini’s opera buffa from the Opéra National de Paris. Stage director Andrei Serban and set and costume designer Marina Draghici found obvious inspiration in the world of classic American cartoons, creating characters that would not be out of place in any episode of Dick Tracy. The eunuchs in Mustafà’s entourage wear eerily realistic prostethic enormous bellies, while his bodyguards don typical gangster suits from the ‘30s.

When he is not an obvious parody of Colonel Kaddafi, Mustafà is portrayed like a crazed version of a late Roman emperor. Isabella enters the stage looking like a dominatrix in latex, and later wears a Harlequinesque gown with the most garish colors human mind can conceive. Occasionally the result is undeniably over the top, such as the distracting gorilla harassing Isabella and Taddeo, or the humongous fake naked breasts hovering over the stage at the end of the first act; at times such tricks verge on the ridiculous, but after all this is one of the quintessential opere buffe.

In 1998 the whole cast was at the top of their game. Larmore had the right type of voice for the title role: sizable, dusky, and especially sexy and sultry. Save for some extreme low notes that are undeniably manufactured, her whole range sounds homogeneous, enabling her to bring out the remarkable quality of a warm, soft-grained timbre. Her coloratura, while not as dazzling as those of Horne, Valentini Terrani or Berganza, is nevertheless fairly precise, accurate, respectable. Idiomatic diction has never been Ms. Larmore’s forte; her Americanized Italian, with its noticeably diphthongized vowels, is frequently too strong to ignore. Physically, despite an awful fright wig of such a black color one would never see in nature, with her curvy, buxom figure she is reminiscent of the archetypical Italian femme fatale.

Bruce Ford brings to Lindoro a darker, even murkier color than that of most interpreters of this contraltino role, as well as a timbre that may not be to everyone’s liking. Technically his voice seems able to execute every vocal trick. He floats his perfectly “in maschera” instrument throughout his impressive range, delivers striking agility, magical pianos (listen to the spell-binding diminuendo on a high B flat at the end of “Languir per una bella”) and is even able to trill on his extreme high notes. My only regret is the cut of a few measures that eliminate Lindoro’s second high C in this aria.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JOQ6jCDYrgI

Although he has never been endowed with a sumptuous, booming voice and his low register has hardly ever been that of a true bass, Simone Alaimo (Mustafà) possesses a secure, proficient vocal framework, with impeccable musicianship and a pleasant timbre. While “Già d’insolito ardore” may be the parody of an opera seria cabaletta, it incorporates vocal difficulties typical of that genre. Alaimo’s exquisite coloratura di forza makes this aria nothing less than an ostentatious exhibition of power. A true stage animal, he creates a real character out of Mustafà, a role that loses much of his range when assigned to buffos, a domain in which the costume designer seems to want to wholly confine him, humiliating him with – among the several extravagant get-ups concocted for him – an unflattering close-fitting tank top and tight gold lame trousers

Since Enzo Dara’s retirement, Alessandro Corbelli (Taddeo) has been reigning supreme as the buffo baritone of choice. He is just perfect in his absolute command of patter-style singing at the service of a rich, attractive instrument. I can only see young Paolo Bordogna rivaling him in this repertoire.

Elvira is a problematic role. While it is true that it is a minor part, she dominates every ensemble she appears in, notably the finale of the first act, where her two long explosive high Cs function as an outlet for the pent up energy accumulated in this impossibly funny page. Unfortunately Jeannette Fischer, made up and dressed like a classic Mafia bride, offers an acidulous soubrettish soprano unable to tower over the other singers.

Anthony Smith (Haly) and Maria José Trullu (Zulma) competently round up the cast, the latter carving out a space for herself thanks to her bustling stage business.

Bruno Campanella shows once more his unadulterated symbiosis with the belcanto repertoire. The numerous pages of cadenced and repeated accompaniments, which often become a monotonous series of guitar-like chords in the best of cases, and heavy hammer blows in the worst, Campanella fills with subtle yet irresistible verve by imperceptibly but constantly changing the weight and color of each sound. The fusion of the voices with the instruments is electrifying.

The Andantino “Pria di dividerci” is wholly suspended in mid-air, ecstatic and interwoven with languorous melancholy and yet is ambiguously voluptuous. In a few words, his conducting is luminous, light, liberating, never sinking to the level of a vulgar farce as it often happens with more ham-fisted conductors.

Precision, brio and effervescence characterize his approach to this opera, which Stendhal defined “as gay as our world is not”.