I have to confess to a certain bias: I adore Rossini’s music. Barber was the first album I ever bought, and fittingly, the first opera I ever sang. Rossini was an astonishingly prolific composer, writing more than thirty-five operas, as well as numerous secular and sacred choral works, songs, and chamber music.

Other than Barber, most of his operas fell out of favor during the early 20th century, I suspect because he wrote for whatever resources he had available at whatever house he was composing for. This makes some of his operas difficult to cast. Barber is easy: a mezzo, a baritone, a basso buffo and a tenor, and the vocal writing is not particularly difficult for any well-trained singer.

Compare Barber, however, to Cenerentola, with daunting extended coloratura passages for Cenerentola, Dandini and Ramiro, and you can see why Cenerentola fell out of the standard repertoire for fifty or so years. Or compare it to Il viaggio a Reims, which was the 19th century version of “Night of 1000 Stars,” composed for the coronation of the French king Charles X in 1825 and written for a dozen or so of the best Italian singers of the period, giving them all showpieces to demonstrate their talents. (Rossini was not shy about plagiarizing himself: thus when the Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique in Paris commissioned an opera from Rossini did Il viaggio a Reims morph into Le Comte d’Ory three years later.)

Otello was written for Naples and premiered there in 1816. Rossini composed Otello after Barber and before Cenerentola. (Well, La gazzetta comes between Barber and Otello.) Supposedly, Verdi was a great admirer of Rossini’s version, and it does have some lovely moments: the Act I duettino for Desdemona and Emila, the Act I finale and all of Act III hold up as well as anything Rossini has written. Naples must have suffered from a surfeit of tenors, as all the male roles save one are tenors: Otello, Rodrigo, Jago, the Doge, Lucio and a gondolier. Elmiro, Desdemona’s father, is the sole exception: he’s a bass. One supposes that this makes Otello a challenge to cast and puts it out of the reach of most opera companies.

The popularity of Verdi’s Otello hasn’t helped Rossini’s case, either. Verdi had Boito as a librettist, and as a composer himself, Boito knew a thing or two about dramatic and musical structure. While both Boito and Francesco Maria Berio di Salsi, the librettist for Rossini’s Otello, took dramatic license with Shakespeare’s play, Boito stayed much closer to the source than Berio, and Rossini’s version suffers in comparison because of it. In eliminating Casio, Berio left Iago (Jago) with no motivation for vengeance, so he had little choice but to have Jago and Rodrigo be in love with Desdemona.

In both Shakespeare and Verdi, Iago is evil: in Rossini, he’s just petulant. To keep things moving along, we are no sooner introduced to Otello than we move quickly to Jago and Rodrigo plotting against him and framing Desdemona. Thus, there are no scenes between Otello and Desdemona where he is not angry with her, rendering Rossini’s Otello a rather one-dimensional character. In fact, in Rossini’s version, Otello feels like a supporting player in his own opera.

Unsurprisingly, there are few recordings of this opera: the best known is probably the 1978 recording with Carreras, Von Stade and Ramey (which I must confess to owning.) Opera Rara also issued a recording in 2000 with Bruce Ford and Elizabeth Futral which includes some alternate material (including a “happy” ending!) Rossini was willing to throw out or replace arias, or even rewrite an opera based on the musical talents or dramatic tastes of whatever opera house was performing his work. For this reason, there is also a version of Otello written for Maria Malibran as Otello.

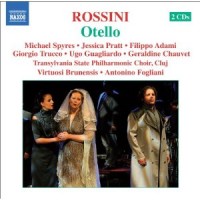

I’m giving you all this background because the opera’s back story is more interesting than this recording. Produced in 2008 with the Rossini in Wildbad Festival in Bad Wildbad, Germany, this is at best a journeyman’s effort. This was the first time I had heard, or heard of, any of the singers on this recording, and for the men at least, I think it will probably be the last. Finding three tenors who can handle the demands of this score cannot be easy, and unfortunately, the Wilbad Festival wasn’t entirely successful.

Michael Spyres as Otello sings passionately and can handle the large range the role requires, but he has an unappealingly fast vibrato that gives him a bleating sound. Filippo Adami as Rodrigo is out of his element: throughout the opera, his nasal tenor is noticeably flat and the coloratura, muddy and inaccurate. Rodrigo gets one showpiece, the Act II aria “Che ascolto? ahimè, che dici?” and it is the low point on the recording. Only Giorgio Trucco as Jago comes off well among the tenors, and I use the term “well” in the relative sense. The score gives Elmiro, Desdemona’s father, little to do, which is good, since I doubt Ugo Guagliardo‘s woofy basso would stand up to a more demanding part.

The women fare better. Jessica Pratt as Desdemona sings with a lovely, clear tone. She does especially well in the third act and makes the most musically and dramatically of the aria “Assisa a’piè d’un salice.” I didn’t have the score in front of me, so I can’t be sure, but I suspect some of the high notes were interpolations. If so, they were appropriate and tasteful choices. Geraldine Chauvet is a fine Emila and their Act I duet “Inutile è quel pianto” shows both their voices to good effect.

Antonino Fogliani keeps the orchestra unobtrusive on this live recording, but it is a testament to the mediocrity of the soloists that the most appealing singing comes from the Transylvania State Philharmonic Choir in their few appearances. The chorus sounds rather small in number, but they sang with the delicacy and blend of a chamber choir. If you already own all the other recordings of Rossini’s Otello and simply have to own this to make your collection complete, then by all means, get it. Otherwise, pass.