My personal exposure to the art of Daniela Dessì dates back to 1981, when she was taking her first professional steps under the tutelage of Rodolfo Celletti, one of Italy’s foremost vocal experts and teachers. I remember her as Berta in Il barbiere di Siviglia at the Festival della Valle d’Itria, where she performed a highly decorated version of the old maid’s “aria del sorbetto”. In the first decade of her career the Genoese soprano made a name for herself principally in the 18th century repertoire (Pergolesi, Salieri, Traetta, Cimarosa etc.), Mozart and some belcanto. Her fiery temperament soon led her towards the “big stuff”. I remember an interview in 1990 where she declared that she felt she had truly sung opera only after performing Marguerite in Faust.

Ms. Dessì’s imminent return to the Metropolitan Opera as Tosca may explain the reason this DVD

of La fanciulla del West is being released in the United States only now, five years after its Italian distribution. The DVD was filmed live at the Puccini Festival at Torre del Lago in 2005, marking Dessì’s debut in the role.

Minnie is arguably Puccini’s most arduous soprano part, a veritable “monstre” role, ranging from a low B to a high C sharp, with a high, jagged, taxing tessitura that has often tried and defeated many of her illustrious colleagues. It also requires a strong middle voice able to penetrate the particularly dense orchestration. Finally, the soprano must possess the naturalness and simplicity for the “canto di conversazione” that abounds in this score.

The success of this opera is contingent mostly upon Minnie and her ability to sing and act. A shy and restrained soprano will doom the opera to boredom. On the other hand, if Minnie is way over the top, she risks becoming a caricature. Daniela Dessì has found the right balance. With a blazing intensity that never gives in to vulgarity, she sounds completely spontaneous and genuine in the recitatives and arioso of the first act, abetted by a voice that is attractive, rich and creamy in her middle range. She knows how to caress the sound while at the same time making every word intelligible.

Truly remarkable is her ability to change color and accent with the same instantaneous rapidity of the orchestra, and her belcanto background is easily discernible in the way she handles the Allegretto “Oh, se sapeste”. Whenever the action becomes dramatic, Ms. Dessì reveals an imperious articulation of fraseggio, a “conditio sine qua non” for this role.

A certain metallic quality sneaks in on her extreme high notes, especially when she sings forte. Nevertheless, this is not so frequent and invasive as to be become distractive. Her top in this performance is generally reliable: the high C in “Laggiù nel Soledad” is steady and solid, and even the C sharp in the second act duet with Rance is plausible. The B natural on the phrase “Su, su come le stelle” in the first act duet with the tenor is splendid, long and firm, a true gem.

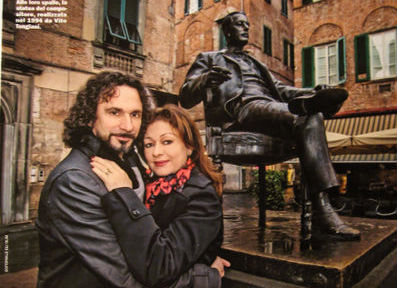

Dessì’s stage (and life) partner, Fabio Armiliato could be easily described as the artistic antithesis of the soprano. His Dick Johnson tends to be bombastic, reluctant to nuances and gradations, with a limited palette of colors. To Mr. Armiliato’s credit, his instrument is a healthy one, with a secure, sonorous top. Lending a sort of generic fervor and excitement to the role, Mr. Armiliato offers a solid, reliable performance, without bothering to dig deep down Dick Johnson’s personality. As they do not grow on trees these days, I guess I should be content with a spinto tenor capable of getting to the end of this opera with no signs of fatigue.

Lucio Gallo disappoints as Jack Rance. His baritone is too light for the role and sounds dried up and devoid of overtones.

One of this opera’s biggest problems is the large number of secondary roles: if these are not assigned to competent performers, the first and the third act are in serious danger of falling apart, a risk here averted by the generally good quality of the character singers. It certainly helps that they are all Italian native speakers.

Alberto Veronesi, director of the Puccini Festival and newly appointed musical director of the Opera Orchestra of New York, is an impressive conductor. It is not difficult to vividly perceive his fiery and theatrical rhythm; the conviction with which he leads the first act duet between soprano and tenor, to which he imparts tenderness and élan with no fear of sounding sentimental and syrupy; or the orchestra’s pulsations and their timbric variety during the poker game.

I would like to single out the blazing second act finale, expressive peak of Puccini’s orchestration. This piece is particularly arduous to carry out because of its structure of eclectic cohabitation among Schoenbergian Sprechstimme, lyrical fragments, orchestral timbres and rhythms, which spin around, modify and return in the space of just a few measures. Veronesi holds the reins of the entire scene without ever letting the tension drop.

Occasionally the Italian conductor exaggerates: for instance, in the second act, when Minnie and Dick Johnson finally kiss: it sounds like the Apocalypse, and even if they had reached an orgasm, it would be always useful to remember the immortal motto of Jacques Vallée Des Barreaux “Voila bien du bruit pour une omelette”. Ditto the end of the opera, when Minnie comes to rescue Dick Johnson: you would think it is Brünnhilde trying to save Siegmund.

One minor disappointment is the customary cut of the sixteen bars of music Puccini added to the score for a 1922 Roman revival of the opera. Concluding with a high C in unison, these bars represent the climax of the second act love duet, and once you have heard them, you feel there is something missing if they are omitted. In truth, the added music is so punishing that even the 1922 protagonists refused to sing it, and Puccini was only able to hear it the following year when legendary diva Giulia Tess and tenor Carmelo Alabiso performed the opera in Viareggio. By all accounts, though he was fully aware of the difficulty of those new measures (in a letter he writes: “Ci vuole gola, però!), Puccini’s final wish was for this music to be integral part of his masterpiece.

Ivan Stefanutti‘s production, with sets and costumes by American artist Nell, is for the most part traditional looking, down to the “A home for the boys” sign on the Polka saloon. Its grandiosity is perhaps a tad out of place: Minnie’s dwelling, a huge space complete with elaborate lace curtains, looks less a humble “capanna” than a high-end brothel. Nell’s eccentricity comes to the limelight in the third act, where two tall human thighbones replace the libretto’s giant redwoods. The costumes are period appropriate, except for the one worn by Minnie in the last act, where, together with a Davy Crockett hat and fur epaulets, she dons a garish burgundy long gown with a long gold-striped mantle of the same color.

So as to burnish her credentials as one of the leading Puccini sopranos of our time, Daniela Dessì has also recorded a brand new CD (released by Decca) entirely devoted to the Tuscan composer. All of his operas, except for the Le Villi, Edgar and Il tabarro, are represented, and in the case of La Bohème and Turandot, the arias of both soprano roles are performed.

This CD confirms what I wrote earlier about Dessì’s appropriate sense of style in this repertoire and her thorough grasp of the requirements of the so-called “verismo” Italian opera. Examine for instance the opening aria, “In quelle trine morbide”: the attack on the B flat is perfectly centered and delicate; when singing the words “carezza voluttuosa” she executes an almost imperceptible portamento that sounds exactly like a sensual caress, and the rolled “r” of “labbra ardenti” is erotically charged. In a few words, we are in the presence of that elusive idiomatic style which has become “rara avis” in this age of homogenized international superstars.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DwjPf5x68Mo

Once more, Ms. Dessì shows her technical prowess, with floating high notes, long interminable breaths, and skilful messe di voce. I was impressed by the final B flat in “Un bel dì vedremo,” and especially the end of “Vissi d’arte”, where she executes the tricky passage B flat-A flat-G in perfect pitch and without running out of steam.

This said, it is undeniable that traces of metallic sound on some of the extreme high notes are present in this recording as well, perhaps a bit more frequently than in the Fanciulla DVD. After all, this is not an album introducing the soprano “du jour”, but the summary of a thirty-year long career, most of which spent performing some of the most onerous roles of the Italian repertoire, including nearly ninety performances of Tosca.

Obviously some arias are vocally more suited to her voice than others. Unsurprisingly, the less felicitous rendition is “In questa reggia”; if the first part aptly expresses Turandot’s psychological alienation, the final section reveals too much friction in the sudden ascents to the high register, and her Calaf (it goes without saying, Fabio Armiliato), not very gentlemanly drowns her high C. Let us hope that the soprano will not be tempted to tackle the icy princess’ role on stage.