Isn’t it Puccini’s intention, or at least most audiences’ notion of Puccini’s intention, that the Roman diva should appear at the Castel Sant’Angelo in the same gown she wore to sing at the gala at Palazzo Farnese and to slaughter Scarpia? Isn’t this yet more evidence of Bondy’s (and, by extension, all those silly stage directors’) ignorance of tradition and contempt for the text?

No.

In the Sardou original La Tosca, Scarpia’s headquarters is located in the Castel Sant’Angelo; therefore after her act of self-defense, Tosca needs merely to go to another part of the fort to rescue Mario, a matter of minutes. Sardou has established earlier in Act 4 that Tosca and Mario have been held at the fort for several hours since they were arrested at his villa. Thus the time line of the action is not only plausible, but is clearly demonstrated to the audience to be so.

But not in the opera. In condensing a five-act, six-setting drama to three acts, Illica and Giacosa provided Puccini with a somewhat different set of situations from Sardou’s. Tosca is questioned not at the Castel Sant’Angelo but at the Palazzo Farnese, not in the wee hours, but immediately following her appearance at a post performance there. Mario’s execution, though, remains scheduled for dawn the following morning at Sant’Angelo.

Now, we are told at the beginning of the second act that the band downstairs is “strumming gavottes” to fill time until the arrival of the diva. Surely we cannot be expected to believe that the Queen of Naples would hang around a ballroom until dawn waiting to hear a measly three-minute cantata, or that even so capricious a diva as Tosca would have the gall to insult the royal lady by standing her up this way. So the librettists are stuck with at least a few hours for Tosca to (ahem) kill between her murder of Scarpia at Palazzo Farnese and her (just pre-dawn) arrival at Sant’Angelo.

Now, here’s the problem. Tosca would hardly require three hours to travel from one location to the other, since the distance between them is barely one kilometer. So the librettists added a line for Tosca in Act 3 with no parallel in the play, “Senti… l’ora è vicina; io già raccolsi / oro e gioielli… una vettura è pronta.” What took her so long? Why, she has been busy during those hours gathering her gold and jewels — to defray the cost of the planned sea voyage — and hiring a carriage for the journey to Civitavecchia.

Under these circumstances, logically she would surely change her (blood-stained, easily identifiable, impractical for traveling) dress as well. If Puccini didn’t want her to change her dress, he shouldn’t have allowed the line about “gathering gold and jewels” to stand.

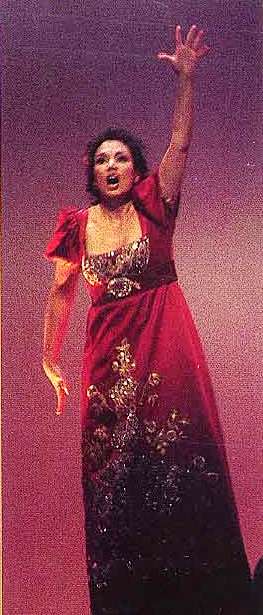

Carol Vaness takes the leap. Note the red silk dress which has held up remarkably well against attempted rape, bloodstains and sight-reading a cantata with a very tricky high C.

But, I hear someone complaining, we always see Tosca in her red dress with a plain dark woolen mantle thrown over it, so surely that must be right! But this drab cloak — can one really imagine the great diva’s wearing such a thing to a royal audience at Palazzo Farnese earlier that night? “So where did she come by it?” one should ask. But nobody ever does, because opera goers are so innured to sloppy traditional habits (many of them contrary to the composer’s stated or implied intentions) that they mistake what they’ve always seen for what is right.

To use an example from another opera, how many times have we seen the entrance of the cigarette girls in the first act of “Carmen” staged along these lines: the bell rings, the doors of the factory open, and the girls saunter out. Eventually Carmen arrives, last of the workers to take her break, and after a hiatus barely long enough to sing the Habanera, all the females return to the drudgery of tobacco-rolling.

This is of course nonsense. Both bells we hear are calling the girls back to work after they have taken a long midday meal and siesta. As with school bells or theater bells, the first bell is a warning, then the next bell is “final.” In fact, the text of the chorus for the young men says very clearly “La cloche a sonné; nous, des ouvrières: Nous venons ici guetter le retour.” And yet, even now one only rarely sees what “the composer intended,” i.e., the cigarette girls returning to the factory, with Carmen taking her own sweet time getting back to work.

You can’t have it both ways. You can’t snipe at those darned stage directors for disrepecting the libretto, then turn right around and say, “Oh, well, in this case I’m used to seeing the libretto flouted, so I’m going to make an exception.”