Where once the countertenor was found in either Britten or Handel, some are stretching their wings and tackling more Romantic repertoire.

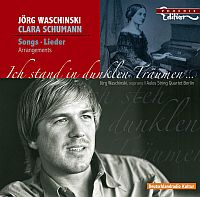

Jörg Waschinski, a German sopranist, tries to wrap his voice around some of the more well known songs of Clara Schumann (Ich stand in dunklen Träumen, Naxos Phoenix170) and achieves mixed success.

Let’s face it: the countertenor or sopranist sound is an acquired taste. Effortless singing presents a greater challenge in the male head voice, as a great amount of air is required to support the sound up there. To my ears, Waschinksi’s sound is a little weak and reedy. The slight tightening of the throat on the attack and release of notes gives the sound a bit of an aged, “end of career” sound. And as the melody drops down towards the passaggio, the sound tends to dry out and weaken.

Waschinski though does demonstrate an expert lied singer’s ear for phrasing: this is some lovely, musical singing (if a bit vocally unsteady — he struggles at the climactic notes of “Der Wanderer” a bit; long notes in “Die Gute Nacht, Die Ich Dir Sage” sound pinched.) But overall phrasing is sensitive to the lyrics and melodic line, if a little unsubtle.

Waschinski thought it would be a good idea to present these songs with string quartet, as he wrote the arrangements. Why do this when Clara Schumann wrote so beautifully for the piano? The arrangements are fine for what they are, but the use of string quartet completely changes the character of the songs. This is especially true of songs with more intricate piano accompaniments, as in “Ich Hab in Deinem Auge,” where the string arrangement distracts from, rather than enhances, the singing.

I wouldn’t recommend this disc to someone unfamiliar with Clara Schumann’s work. Not only do you miss the Schumann piano accompaniment, but Waschinski’s idiosyncratic sound may get in the way of appreciating the songs. I have a recording that must be, oh, about ten years old now, with Barbara Bonney singing the songs of Robert and Clara Schumann, and Waschinski suffers in comparison. And that older recording has Ashkenazy on the piano to boot.

Born on the windswept tundras of Russia (or Scotland or Chicago, she can’t quite recall as she was very young at the time), Violetta D. Pensateci learned two things at her mother’s knee: what a bony knee looks like, and how to appreciate opera. She studied singing with the magnificent Nancy Kulp and made her professional debut and subsequent farewell performance in one evening as the Madame in Butterfly. She now works as a waitress in a disreputable restaurant and devotes her free time to charitable work such as thinking of the children and giving up one cup of coffee a day.