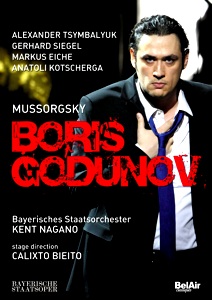

Let’s face it—there is no operatic suffering like Russian operatic suffering. In Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, all the Russian people starve and suffer, but none has suffering like the mental agonies of Tsar Boris. Now add to this suffering the sharp edge of a modern police state setting and numerous acts of violence brought by Catalan director Calixto Bieito, and you have one of the darkest, gloomiest, and bleakest performances of Boris Godunov ever, a Bayerische Staatsoper production from Munich 2013, released

by Opus Arte.

Bieito’s frequently used theme of a state where government oppression of its people has run wild both socially and economically, is very much in play here. The opera opens with a crowd being forced into pro-Boris demonstration by Nikititch and his band of threatening police officers. Anyone who objects is brutally beaten. The crowd is provided with placards representing leaders of the modern world—Putin, Sarkozy, Bush, Blair, etc.

Led by Prince Shuisky, the crowd is manipulated into demanding that Boris become Tsar, and, when he appears, they cheer him and wave flags, though without much spirit. In this production, Bieito spares us his usual full-frontal nudity and various acts of simulated sex (both employed liberally in his recent production of Tennessee Williams’ Camino Real that I attended at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago), replacing these with violence at every turn. This production might be subtitled “No One Gets Out of Here Alive”.

The production uses the “First Version” of the opera from 1868-69, dividing the piece into seven scenes which compresses the action without the diverting if unnecessary Polish Act. Bieito’s direction keeps the opera’s story snowballing toward its conclusion, but does add some seemingly distracting touches. Boris’ daughter Xenia is an apparently drug-addled, fur wearing ditz; his son Fyodor, inexplicably, is a uniformed schoolgirl played by an adult female. It is this choice that is most mystifying—why? If Bieito is trying to make some sort of statement about roles for women, it is jaw-droppingly ham-handed. I did enjoy Fyodor’s map of Russia taking the form of a beach ball, left uselessly on stage when the child becomes distracted.

But let’s talk violence and murder. In the scene at the inn when Grigory is trying to escape to Lithuania, the hostess of the inn (here wheeling in a food cart) first whips her little daughter mercilessly for no apparent reason, and then helps Grigory escape by shooting the border guards (one of whom is stabbed by Grigory). In the fourth scene, the Simpleton is tormented by a tribe of vicious children, one of whom shoots and kills him, goaded on by Shuisky.

But Bieito saves the real Grand Guignol for the finale. As Boris is dying downstage, Grigory arrives, strangles the children’s Nurse, then proceeds to strangle Boris’ daughter and smothers the Tsarevitch Fyodor with a pillow. Boris’ moving death scene is overshadowed by the carnage upstage. Yet Bieito does succeed in showing how brutal are the power struggles of the modern state.

Bass Alexander Tsymbalyuk gives a potent performance as Boris, and his liquid tone makes this the best-sung Boris of my experience. There is no barking, no posturing—Tsymbalyuk has a beautiful timbre and is a fine actor to boot. His descent into madness and death is genuinely harrowing. Also splendid is Anatoli Kotscherga as Pimen, his haunting final scene telling of the story of the ghost of the murdered Tsarevitch a highlight. Sergey Skorokhodov is appropriately icy as the pretender Grigory, and tenor Gerhard Siegel brings a nice touch of ambiguous malice to the role of Prince Shuisky.

There was much criticism at the time of Kent Nagano’s conducting, but I found that he gave a chilling reading of the score that matched the production. The delicacy of the music that accompanies the death of Boris was powerful; the Bayerisches Staatsorchester playing with passion in climaxes and nuanced subtlety in emotional moments. The Chor der Bayerischen Staatsoper sang well and acted gamely.

The dark, dense, foggy set from Rebecca Ringst seemed appropriate for Bieito’s production, though it added to the relentless sense of gloom that pervades this performance, where there are no characters whatever to like or admire, and Boris, like the audience, is trapped in a world where cruelty has become the norm.

Comments