William Christie turned 80 on December 19 this year. He chose, as his birthday present, to conduct Rameau’s Les Fêtes d’Hébé in a new staging by Robert Carsen, at the Opéra Comique, Christie’s thirteenth production there since the famous Atys of 1987.

In doing so, he offered a magnificent Christmas present to us all. As this is one of Rameau’s best, but not best-known, works, I’ll begin with a little bit about it. As usual, anyone not needing an intro can skip it.

Premiered in 1739 by the Académie royale de musique (now the Paris Opera) in its Palais-Royal house, Les Fêtes d’Hébé, ou les Talens Lyriques (or Talents Liriques, as the cover of the score in France’s National Library spells it) is the composer’s second ‘opéra-ballet’, after Les Indes Galantes (1735). It followed Castor et Pollux (1737), which I’ll see later this season at the Palais Garnier, and is one of the works in which Rameau recycled music composed for the Samson(1734) that he worked on with Voltaire – banned by the censors for mixing the sacred and profane and therefore abandoned. Claus Guth and Raphaël Pichon have put together a reconstruction-cum-pastiche of Samson, performedin Aix in July this year, and I’ll see that at the Opéra Comique next spring.

In 1739, Rameau, by then in his mid-fifties, was at his peak. Despite its feeble libretto, criticized from the outset and revised within months of the premiere, Les Fêtes d’Hébé contains some of his most inventive and variegated music, whether comic, tragic or pastoral, and was one of his greatest hits. Rameau claimed he could successfully set the newspaper to music; contemporary writer Guillaume Raynal retorted that having heard Hébé, he could well believe it. With a cast that included Rameau faithfuls Marie Fel, Pierre Jélyotte, Marie Pélissier, and the dancer and choreographer Marie Sallé as Terpsichore, the work initially ran for six months non-stop, every night the house was open, and was performed nearly 400 times in all during the composer’s lifetime.

The plot is, if possible, slighter still than that of Les Indes Galantes, and takes the same form: a Prologue and a series of ‘entrées,’ alternating song and ballet. In the present case, these are three short stories of love first thwarted but eventually prevailing, that celebrate the combined powers of youth and poetry, music and dance in turn. In antiquity, Hébé was supposed to have been banished from Olympus for spilling the gods’ nectar. Here, she is led by the Zephyrs (or in this production, sent, on a bicycle) to the banks of the Seine, where the action, such as it is, takes place.

All you need to know to follow Robert Carsen’s clever updating is (1) that French president Emmanuel Macron’s nickname is Jupiter (on account of his supposedly Olympian presidential style); (2) that each year, the City of Paris transforms the Seine embankments into a ‘beach’ area, with deckchairs, games and dancing, called ‘Paris Plage’; and (3), supposing you didn’t know already, that the 2024 Olympic Games took place in Paris, after an opening ceremony along the river, and ended, as the Olympic flame ascended in a balloon, with Céline Dion singing Piaf’s Hymne à l’amour at a sparkling Eiffel Tower.

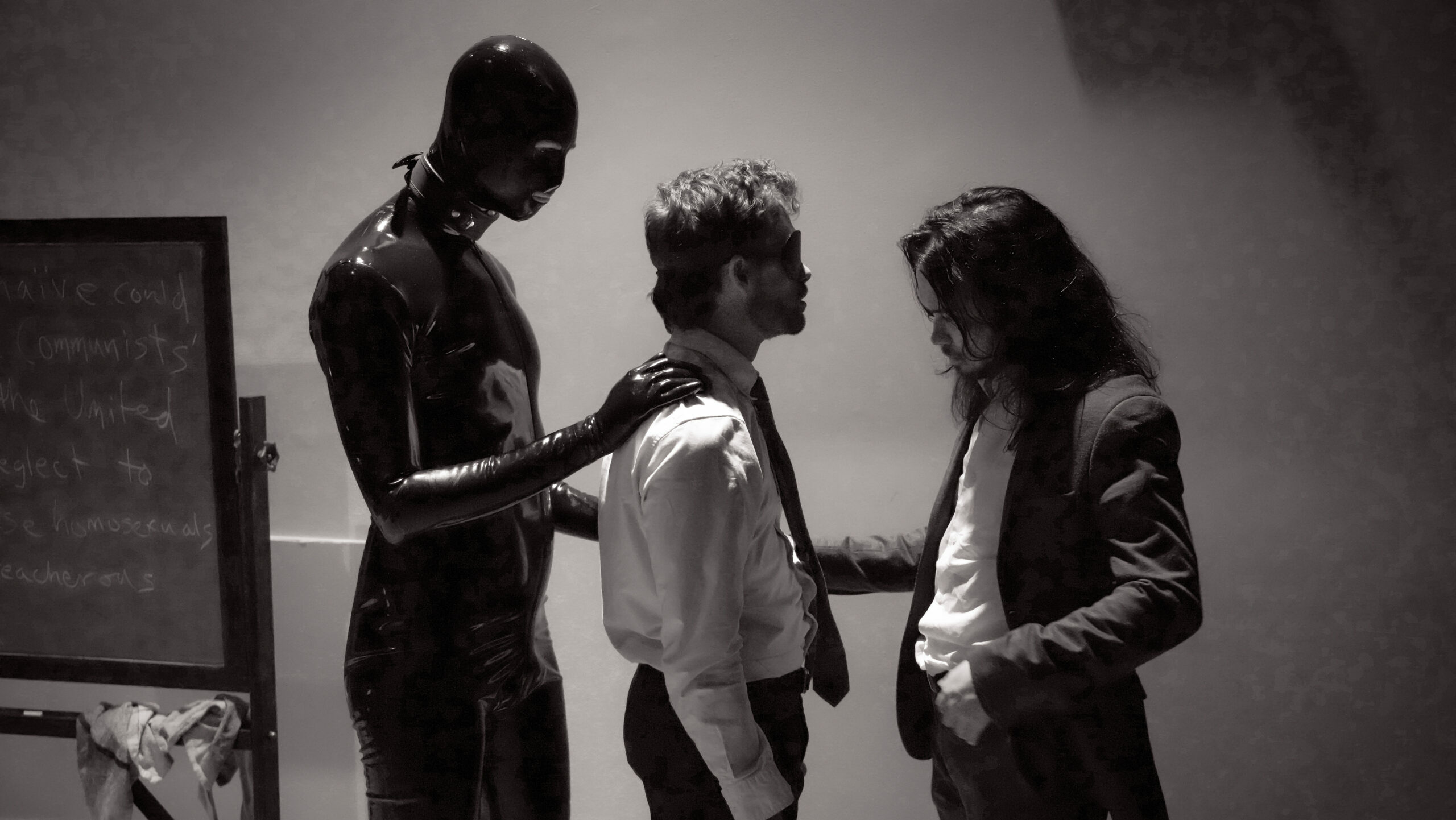

At curtain-up, Robert Carsen’s production swaps Olympus for a photographic mock-up, columns, chandeliers and all, of the Elysée Palace, seat of the French presidency. Emmanuel Macron and his wife Brigitte — played by lookalikes — are entertaining guests in suits and cocktail dresses, some carrying briefcases. Disaster strikes: Hébé, a waitress, trips and spills red wine on Brigitte’s immaculate white ensemble. She is fired on the spot by Macron/Jupiter. She leaves, followed by Momus. The guests pour out to form a line at the taxi stand. Amour, here a glamorous influencer in a long, red, satin dress slit to the thigh, ropes in the two handsome, grinning policemen guarding the entrance to take photos while she strikes a series of increasingly zany voguing poses before the palace. The queuing guests brandish their smartphones to capture the scene as Amour consoles Hébé and urges one and all, including Hébé on her bike, to gather for fun and games on the banks of the Seine. It is already obvious by this point that Carsen has given everyone on stage, individually, specific comic directions, followed with alacrity.

The first entrée, La Poésie, finds us at Paris Plage. Young employees in turquoise polo shirts, name tags round their necks, are setting up deck-chairs under a row of potted palms on the embankment. The Elysée guests change on stage into colorful beachwear (this counts as a ballet, though no-one actually dances), and a visibly chuffed chief of France’s CRS riot police takes the place of Hymas, King of Lesbos, to watch the show devised by Sappho. Her success is such that cartons soon arrive, filled with books of her poetry, hot off the press and handed out to her fans, the guests. Thelemus, the unlucky suitor, is garlanded with seaweed and chucked into the Seine with a splash.

The second entrée, La Musique, is set on a Left-Bank quayside, complete with bouquinistes’ dark-green booths on the parapet, and (video) plane-trees above, rustling gently in a summer breeze. Princess Iphise, here already in a wedding dress and veil, may only marry a hero who has defeated the Messenians; in Carsen’s vision, Tyrtaeus is the captain of France’s soccer team, who arrive on the river (i.e. through the auditorium, house lights on) and set off to challenge the Greeks. They return victorious, with their delirious fans, the former Elysée guests, now brandishing flags and scarves. There follows a fascinating soccer mime/ballet, in which feet kick and eyes follow invisible balls. Iphise, of course, marries the coach.

In the third and final entrée, La Danse, a little blue DJ’s shack is set up on an embankment with a broadside view of Notre Dame and her spire, beside a dance floor staked out under strings of bare bulbs. Mercury arrives on a motorbike and takes over the turntables. Eglé’s suitors (there’s a dance-off for her hand) and her virtuoso dancer friends wear contemporary party clothes: fancy dinner jackets, shiny fabrics, spangled tops. The villagers who rush to her wedding with Mercury are, of course, none other than those Elysée guests again. The luxuriant garden evoked by the stage directions is the Hébé, a cardboard cut-out bateau Mouche, with Hebe herself as tour guide. All aboard, the whole crowd set gaily off west along the Seine, gleefully snapping photos and selfies as they go (the whole production is under the sign of Instagram), till the Eiffel Tower looms up and bursts into sparkling lights against a background of fireworks. Curtain – and applause, lots of it.

I said just now that Carsen’s updating of the plot was ‘clever’. It was very clever, as by keeping us wondering what the next, fun clin d’oeil at contemporary France would be, he eliminated any risk of boredom. To create a narrative thread for a libretto that didn’t previously have one, he linked the three entrées together under the single, Paris Plage concept, and hit on plausible, amusing contemporary transpositions of the antique story without resorting to slapstick gags. Carsen is Carsen: it’s funny, but still chic. At a pinch, you might complain that street-inspired dance in Rameau is now déjà vu; but people lap it up, and I don’t think anyone there was in a mood for complaining. Far from it. The detailed action is beautifully managed, to the last glance and gesture, from start to finish. The athletic, witty ballets merge seamlessly with the action and singing, and make unusual demands on soloists and chorus, proving that Lea Desandre, who actually has a sinuous, solo contemporary dance of her own in the final entrée, and others do more than ‘just’ sing.

But sing they do. It’s always hard to do justice in writing to music and singing at this high standard. What can you say, other than that everything was fab? William Christie is capable, as we know, of casting weak singers. (A friend of mine calls these his ‘voiceless wonders.’) Singing Rameau isn’t a stroll in the park: his idiom calls for a demanding mix of declamatory skill with vocal agility and flexibility of a kind that at times almost recalls classical Middle Eastern songs. It’s hard, and you can’t just wander into it from other rep and carry it off. But in this cast there wasn’t one weak link. Here, everyone, from the smallest to the stars, had both the proper style and — mirabile dictu — good diction; what a relief not to spend the evening glued to the supertitles. And not a single countertenor in sight. The chorus was on top form, and no amount of simultaneous acting and dancing could throw them off the beat. If there was one weakness, it was perhaps the minor quibble that the voices in the lower male supporting roles tended to peter out at the bottom: a familiar issue.

Emmanuelle de Negri, who’s sung with Christie for at least fifteen years, set the joyful tone of the evening as Hébé, deploying a darkish, supple soprano voice with vivacity and presence. Cyril Auvity, another ‘Christie veteran,’ eternally youthful (if now grey at the temples) remains instantly recognizable, singing more forcefully and steadily than on occasion, right to the haute contre top.

Ana Vieira Leite and Lea Desandre were both way better employed here than they were straying into Médée last spring at Garnier, where they sounded two sizes too small. Still, I noted then that ‘Ana Vieira Leite sings beautifully, with a pretty, silvery sound,’ and here she combined that with vivacious comic acting as a glamorous, slightly ditzy but determined influencer. Lea Desandre seemed to ‘own’ her three roles, showing remarkable ease in the style: supple, subtle, varied in color and dynamics… It was as if she’d sung them all her life. She was quite obviously the vocal star of the evening. And even more than the rest of the cast, her singing, acting and dancing were all one, forming an integrated whole.

Only that stardom was very nearly snatched away from her at the last hour by Marc Mauillon. The role of Momus doesn’t really offer the chance to shine. But Mercury is Mercury and was originally sung by Jélyotte. His easily recognizable arias — florid, brilliant and high — are among the hardest in Rameau to get right. Mauillon did it, putting in an astonishing performance that, to be honest, based on past experience, I had no idea he had in him. Not, I think, since Topi Lehtipuu had I heard one of these dazzling, clarion-call arias carried off with such gleeful brio.

William Christie, at 80, conducts Rameau with even more vigor than ever. I’ve tended, in the past, to associate him with a delicate, feathery, touch, even if his tempi have always been brisk. But here, with quite a large orchestra including four oboes, four bassoons, and a musette, the playing was not just vigorous but rich, colorful, and beefy — more ‘muscular’ than usual. His years of French baroque have culminated in absolute mastery of the style, giving him freedom to navigate, with his players and chorus, the most striking variations in color, tempo, rhythm and dynamics. If, above, I wrote that Lea Desandre was the vocal star, it was so I could now say that the real stars of this particular show were, indeed, Christie and his players. A feast. He looked as pleased as punch during the curtain calls, and as usual led an encore from the stage while capering, in his dapper white tie and tails, with the cast.

On Tuesday evening, ticket touts were out at the Métro exits, scouting for spare seats. I’m not sure they found any. The house was packed. But not once, remarkably, did Christie need to turn and scowl at people coughing or phones tootling. At the end, of course, the silence exploded into cheers. He conducted again on Thursday: his birthday. I should imagine the cheers, for Hébé but also for all the conductor’s long career in France, in support of French 18th century repertoire, were louder still.

Photos: Vincent Pontet

Comments