Also debuting that night: soprano Gundula Janowitz (Sieglinde); bass Karl Ridderbusch (Hunding); Walküren Gwendolyn Killebrew, Phyllis Brill, Barbro Ericson and Rosalind Hupp; and designers Günther Schneider-Siemssen and George Wakhevitch.

Conrad L. Osborne in the London Times:

I wonder if there has been in our time a lesson in cultural politicking like that taught by the von Karajan Ring Cycle. Here is a production created in two major centers, one an important spring festival, the other an international opera house, the joint nature of the enterprise being used as amortization against what would otherwise be prohibitive costs in time and money. And here is direct and indirect financial support being drawn from the contemporary equivalence of the bygone patrons of art: the other, wealthier entertainment media (television, films and a record company, on the German side) and a huge corporation of expansive outlook (Eastern Airlines, underwriter on the American side to the tune of $500,000). Pre-requisite: a man who combines artistic stature with a feel for power.

The first section of the cycle to be placed on view at the Met is “Die Walküre.” There has been a fair amount of grousing about it, and I have my reservations, too. But it is incomparably the best Wagner to have been seen and heard at the Met in many years.

To begin (and end, too. I suppose), this is Wagner in the hands of a brilliant, imaginative conductor. It is true, that this conductor’s concept is a subject of legitimate controversy, but it is still the thought-out product of a superior musical mind. As it happens, I sympathize with Karajan’s approach; I found this the most cohesive and beautiful reading of “Die Walküre” in my experience. Most of the complaints center around the first act, but Acts 2 and 3 are proportioned logically in relation to it; it is simply that the scoring of the first act is far lighter and more lyrical than that of the succeeding acts, due to the obvious differences in the nature of the dramatic materials.

After looking through and listening to the comments that followed the first night, I was prepared for an understated reading but found simply a scaled reading, one that kept magnificent balance between pit and stage; that maintained sensible proportion so that climaxes were climaxes, and not just the louder following the loud, and that exuded a subtle but unmistakable tension that drew one into the drama and “forced” one to listen. And that is what happened; for once, a Met audience shut up and paid attention, intent on the progress of the narrative and on the lovely things that were happening in the pit.

Karajan has the wonderful gift of projecting this music in such a way that it seems to happening for the first time (the very rare and precious quality striven for by serious actors and singers), so that though one knows perfectly well what is coming next, one nevertheless leans forward in anticipation to hear it unfold. My own few moments of impatience had nothing to do with the level of volume, which I found entirely satisfying, but with the impulse of the tempo at two or three climatic moments, where both I and the singers longed for a slight quickening which Karajan was not about to grant us.

Acts 2 and 3 were simply stupendous – extraordinary colour and balance and rhythmic rightness, and a delicious quality that I can only call “wholeness” in the sound, so that the clarity was achieved without vivisection of the score. It remains to be said that the difference between the playing secured from the orchestra under Karajan and that secured on an average good Metropolitan evening is downright embarrassing; on the occasion I heard “Die Walküre” the brass tired in the third act but even the occasional resulting burbles would hardly detract from the gorgeous overall impression. I guess that some hearers are bothered by the fact that the singers are so consistently audible. We heard every word, every note, we followed the singers and went with them. In other words, Karajan is doing what used to be considered the essential task of any competent operatic conductor: accompanying.

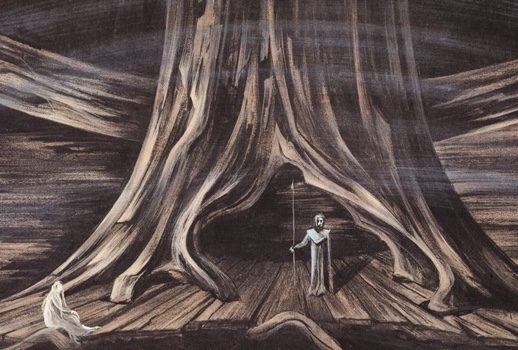

As a director, Karajan is on shakier ground. But again, I’m afraid I feel that the thing everyone is complaining about is being done rather well, while the things that are really being fluffed have stirred no notice. For some reason, everyone is suddenly concerned about lighting. Folk who make no murmur season in, season out at light plots which apparently consist of throwing a master switch profess acute discomfort over the dimness of the stage picture. Nonsense. This “Walküre” is intelligently and poetically lit. It is prevailing dark because it is supposed to be prevailingly dark. The essential mood of each scene is sensitively set, the transitions are steady and well matched to the score, and the principals are lit in a manner that is understated and subtle, but entirely clear and distinct. The lighting scheme allows for the necessary forming and reforming of Günther Schneider-Siemensen’s set, and lets it happen in a natural, albeit eminently theatrical way.

The real problems relate to the behavior of the principals. There is almost never anything specific enough to illuminate the relationships of the characters or to humanize their motives; nearly all the blocking is unimaginative, and some of it (in Act 1 particularly) is almost amateurish. When a character stands or sits or makes a cross, there must be a reason, and the reason most be organic not only to the Meaning of the Drama (?), but to the character himself. It’s not happening.

Comments