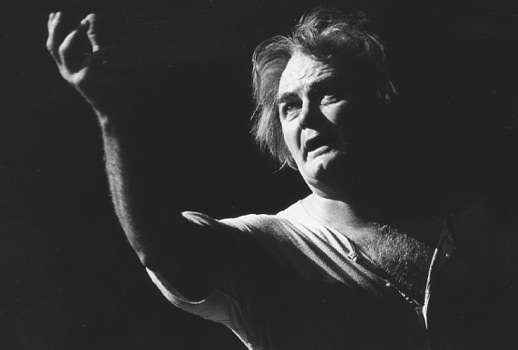

As a light rain fell yesterday, I sat on the side of the road and suddenly recalled the lines of Gurnemanz in the final act of Parsifal: “Denn Titurel, mein heil’ger Held… er starb – ein Mensch, wie Alle! “Titurel, my holy hero, has died – a mortal like us all!” Jon Vickers, a Colossus of the opera world was gone, merely human after all. He was the earliest of my operatic heroes—my holy hero. And the sting of his death hurts like no other.

When it comes to opera, Vickers was part of my Amfortas-like wounding. In 1970, my grandmother took me to see the Karajan film of his Salzburg Carmen production at the Saenger Movie Palace on Canal Street in New Orleans. The Saenger was a setting of proverbial Blanche du Bois enchantment and some ad copy from its early days in the 1920’s described it as “an acre of seats in a garden of Florentine splendor.” What I remember most as a child of eight was the elaborately atmospheric interior, which attempted to replicate a Renaissance Italian palazzo, with all manner of convincing ornamental detail.

Adding to the theatrical illusion was a darkly painted firmament of a ceiling, complete with twinkling stars. Into this magic kingdom, I watched a larger-than-life Grace Bumbry and Mirella Freni vie for the soul of a man played by Vickers with an incandescence that formed the template against which I measured all performers who followed. I often say I was doomed by it all. Or blessed, depending on how you look at it.

This will not be an exhaustive career retrospective or an exploration of the man behind the voice. Both have been thoroughly documented elsewhere. My aim is simply to articulate what I found so life-changing about Vickers the artist and express my gratitude for all he shared.

I returned to that Carmen film last night on DVD and marveled again at the wonder of Vickers’ Flower Song. I have never heard it sung better. In writing about his phrasing as Radames in Opera on Record, John Steane proclaimed: “So beautifully haunted it is, half painfully, half entranced.” It is exactly that haunted quality which was a Vickers trademark. For once, Bizet’s opera is no tawdry true crime story about a low-life slut and her lunatic killer of a lover. Vickers elevated the basic plot outline. He made it into a statement about transcendence, salvation, a common man’s attempt to escape the suffocating ordinariness of life, the pursuit of a heroic destiny.

Don Jose’s aria here is not about erotic or even romantic passion but the discovery of a divinity where one’s soul wanders in bliss, nourished by the scent of a heavenly blossom and the promise of redemptive love. Carmen not only frees him from a literal prison but the prison of earthly despair. Vickers gives eloquent expression to all of this through his tenderly poetic phrasing, culminating in a perfectly executed pianissimo high B-flat at the climax. But it is his visionary rendering of the dramatic situation which is extraordinary.

Vickers once said that “art is a wrestling with the meaning of life” and his portrayals embodied this struggle. Each role carried within it universality, a recognizably existential dilemma as each of his characters fought valiantly to reshape or transform a seemingly inexorable destiny. Like all great dramatic artists, Vickers was interested in complexity. He never sentimentalized his interpretations, never sought to make his characters likeable.

If Peter Grimes demanded moments of frightening psychosis, Vickers did not shirk from delivering full-on cray-cray scariness. There was always an element of danger, of barely contained emotion in everything he did. What is not often commented on is how this quest for dimensionality created space for the unexpected.

Take for example his performance in Karajan’s Pagliacci film. As Vickers depicts him, Canio is no grotesque, aging figure of pity, like Emil Jannings in The Blue Angel, but a vibrant, good looking, even dashing leading man. He is charming in his initial interactions with the chorus, displaying expansive good will, generosity of feeling, a broad, life-loving smile and an almost prophet-like stature as he encourages the villagers to attend the commedia performance later that night.

There is similar sunny warmth to his performance as Vasek in the Met video of The Bartered Bride, a tellingly funny portrayal because he allows the humor to grow out of the befuddled youth’s fear, confusion and excitability. And yet it is all suffused with vulnerability that makes Vasek’s experience into the stuff of heartbreak.

Whatever his difficulties with colleagues backstage, Vickers encouraged a milieu onstage of stimulating, collaborative energy. In a foreword to Jeannie Williams’ biography Jon Vickers: A Hero’s Life, Birgit Nilsson wrote: “I always found it very exciting to sing with Jon, because he gave not only one hundred percent but one hundred and twenty. You would have to be made of stone not to respond to his unbelievably intensive way of singing.”

In the justly famous Norma from the 1974 Orange Festival, Vickers helps to draw forth a performance of staggering completeness from Montserrat Caballé in the title role. He only sang Pollione this once and his free and easy way with the score betrays Vickers’ unfamiliarity with the part. But his committed sparring and ultimate reconciliation with Norma presented Vickers with the opportunity to illuminate the transformation of a morally ambiguous character and Caballe responds in kind with a final scene of blazing feeling and equally textured dramatic richness.

While it is true he could be smug in his judgments about roles, operas and composers, Vickers had his own sense of integrity about the profession of singing and how he chose to invest his creative energy. There was nothing of the conventional tenor about him. He shunned agents, public relations and the whole “business” aspect of being an opera singer. In The Grand Tradition, Steane wrote: “But of course Vickers is not ‘a tenor’ any more than Caruso was… what makes him something that cannot be suggested by the term ‘a tenor,’ he sings with such full soul… one senses an exaltation which might very well be called religious.” I never found this devotion off-putting, self-righteous or fake. On the contrary, I think he was simply trying to inject something of the sacred back into an art form whose very origins were an attempt to recreate the ceremonies of worship practiced in ancient Greece. (Until writing this piece, I never thought of Vickers as evangelizing through art but that is exactly the zeal he brought to his work both on and off stage.)

It was the ancient Greeks who coined the term “catharsis,” or the purging of the emotions through art. Vickers was in the business of catharsis and no more so than in his towering portrayal of the title role in Verdi’s Otello. Watching the 1978 Met telecast again, I consider it not only the finest interpretation of the part but the single greatest portrayal by any operatic artist in my 45 years of operagoing. No other tenor has found and integrated all the disparate elements of this tortured character as Vickers did.

Here for once is Otello the warrior, the statesmen, the lover, the former slave, the marginalized outsider in a treacherous society. Vickers’ protagonist is motivated by a death wish, the cessation of a restless vigilance known by one whose early life has been one of agonizing trauma and deprivation. No wonder he sees a shadow so readily in Iago’s deception. Otello’s experience has led him to believe in the inevitability of betrayal and the only way to unravel life’s terrifying uncertainty is to unconsciously pursue its ending.

The final scene is Vickers at his greatest. Brandishing his scimitar, Otello takes leave of his glory as a warrior (“sweet passing, blessed terror” as Wagner’s Siegfried sings at his own death). After handing his weapon to Lovodico, he then approaches Desdemona and confronts the horror of his demons in action. He apostrophizes her in singing of unearthly beauty. As he calls her name, the realization of his crime overwhelms him.

His cry of “morta” is like the howl of a wounded animal, a moment of such raw emotional pain that I can barely stand to watch it. And in one final act of violence, he plunges a dagger into his heart. There is the sound of “immortal longings” in Vickers singing as he seeks a final kiss and the hope of reuniting with his too well loved wife in the afterlife. As he peers into the eternal, we can now see Otello’s entire life culminating in this moment of release and hopefully peace. Vickers has taken us on a harrowing journey and these final five minutes are textbook catharsis.

And now to the moment of parting: how to say farewell to one of the greatest opera singers of the 20th century? A tenor whose name will forever be synonymous with music, drama and poetry? A man who is for me the essence of what is best in art? Well, something befitting a hero, I suppose. A holy hero.

Now I have his sublime phrases from Die Walküre in my ear: “Then greet for me Walhall, greet for me Wotan, greet for me Wälse and all the heroes, greet too the beauteous wish-maidens.” If there is a Valhalla for opera’s fallen, Jon Vickers has surely earned his place. May Brünnhilde in the form of Nilsson guide her beloved Siegmund there!

Comments