“Do not forget my desire to write operas. How I envy anyone who does,” Mozart wrote to his father in 1778. “But Italian, not German, seria, not buffa.”

In his sixth year in Archbishop Colloredo’s service, the young Mozart was growing frustrated: his last opera seria, Lucio Silla, was produced in Milan in 1772, his last buffa, La finta giardiniera, in Munich in 1775. He had no hopes of writing an opera for the austere Salzburg court, nor would he be able to obtain a contract for a new work in Munich, Mannheim, or Paris during his travels of 1777–79.

But his quest, unsuccessful in attempting to obtain new employment, did bear a different kind of fruit: the commission for Idomeneo arrived from Munich in 1780. Its composition would come to pass under felicitous circumstances, Mozart’s high ambitions being allowed to flourish in the court’s exceptional musical environment. He would have the former Mannheim “orchestra of generals” at his disposal, as well as seasoned court singers (elderly but still virtuoso tenor Anton Raaff, the sisters-in-law Dorothea and Elisabeth Wendling); musicians with whom he had already formed friendships and for whom he had composed during his stay in Mannheim. (Though there were a couple of snags: Raaff was a statuesque actor, and Mozart complained bitterly about the vocal and dramatic abilities of his Idamante, the young castrato Vincenzo dal Prato.)

Mozart could also capitalize on his musical experiences from Paris, notably with Gluck’s French operas. The Gluckian influence, already perceptible in Silla, took shape in the most fully-realized form in Idomeneo. Though not fully adhering to the reformist principles (vocal lines remain considerably more ornate than the ideal of “noble simplicity” would require, and through-composed recitatives are off the table), Mozart departed markedly from the old seria format with the inspired use of accompanied recitatives, choruses, and multiple ensembles, resulting in an overall more fluid structure. It did not hurt that the libretto was based on a tragédie lyrique itself, Antoine Danchet’s Idoménée (set by Campra in 1712), offering the very material favored by “reformed” seria works: a sacrifice drama in the fashionable spirit of the Iphigénie operas, the presence of supernatural forces, and the chorus’ elevation to a prominent dramatic role. Giambattista Varesco’s able adaptation (nudged along by Mozart) opted for the usual lieto fine rather than the French original’s the tragic ending: the Cretan king Idomeneo, who, in return for a safe passage home from Troy, offers to sacrifice whomever he encounters first when coming ashore and duly meets his own son Idamante, gets out of his bind by divine clemency, only having to abdicate his throne.

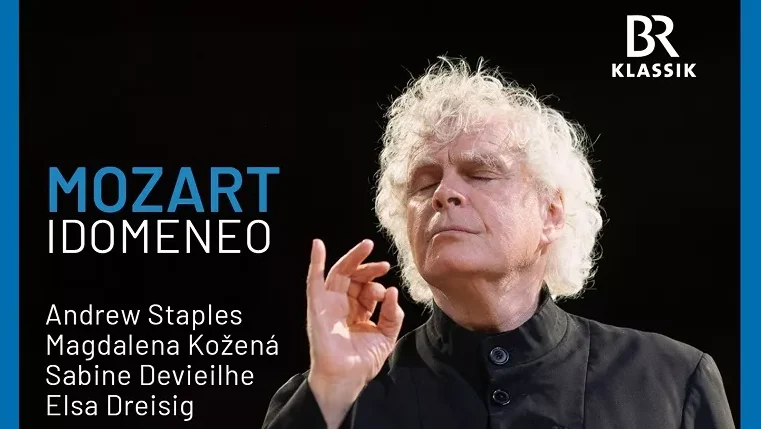

The new recording by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, led by Sir Simon Rattle, lets the work shine in all its youthful, fiery glory. Recorded in December 2023, this Idomeneo marked Rattle’s inaugural season as the BRSO’s new chief conductor. The choice of Mozart’s first mature masterwork seems apt: Rattle has been happy to return to the opera throughout his career, having conducted two productions in Glyndebourne (Trevor Nunn and Peter Sellars’s, in 1985 and 2003, respectively), one at the Staatsoper Berlin (David McVicar’s dreadful handiwork in 2023), and a concert performance with the Berlin Philharmonic (Salzburg Easter Festival, 2004). The latter three shared their Idamante in Magdalena Kožená, who, unsurprisingly, returns on this recording as well, alongside Andrew Staples, Sabine Devieilhe, and Elsa Dreisig.

Though it may not dethrone Gardiner’s 1990 recording as the gold standard for the opera, Rattle’s own is a more than worthy contender in the catalogue. His affinity for the piece, as well as his consistency of vision, is readily apparent in his tightly paced, elegantly phrased, and HIP-inspired reading, with raspy, rough-edged natural brass, some idiosyncratic tempo choices and vivid dynamic accents, but, for better or worse, without the extravagance of René Jacobs (or the fervor of Raphaël Pichon). The fluidity of the opera’s structure, as well as its dramatic momentum, are keenly realized here. The BRSO’s playing is supple and radiant, individual lines staying beguilingly transparent in the score’s tapestry. The woodwinds, prominent in Mozart’s orchestration and playing a major role in providing the obbligato for Ilia’s arias, are mellifluous and spirited, while the timpani punctuate and underscore the dramatic moments with bombastic effect.

As an ensemble, the cast uniformly pleases with well-matched timbres, remarkable attention to the text, and eloquent, attentive phrasing. Andrew Staples, Rattle’s Berlin Idomeneo, assumes the role of the haunted Cretan king with somewhat mixed results, offering a commendable but rarely awe-inspiring performance. His bright, nasal tenor tends to sound a touch pinched, and his Fuor del mar, though respectably accomplished, doesn’t have the unflinching ease of Michael Spyres or Anthony Rolfe Johnson. He does, however, render other passages very movingly: his opening Eccomi salvi alfin is thoroughly dramatic, and his interactions with Magdalena Kožená’s Idamante, notably in their fateful first meeting and the sacrifice scene, are all deeply affecting.

The rest of the cast is thoroughly satisfying. Idamante has been an old friend for Kožená and that familiarity is on display here in her remarkable textual sensitivity, along with a strikingly youthful, glowing tone and security throughout her range, skillfully navigating the role’s soprano-ish heights. Kožená’s offers the right mix of boyish passion and general wretchedness, at turns tender, hopelessly pleading and just a touch scornful in Non ho colpa, and both devastated and devastating in Il padre adorato. (It’s dramatically understandable but still a shame that No, la morte is omitted from the sacrifice scene.) She’s ideally matched with Sabine Devieilhe, slender-toned but pure and luminous, as heavenly an Ilia as they come. Devieilhe’s portrayal of the captive Trojan princess is arresting from the very first wounded line of her opening recitatives. Through Ilia’s conflicted arc from dutiful self-denial to the elated love confession and willingness to sacrifice herself for Idamante, Devieilhe’s performance only grows more captivating. She’s ethereal in the charmingly ornamented Se il padre perdei, and her effortlessly floated Solitudine amiche … Zeffiretti lusinghieri makes time stand still.

Vocally of similar stature as Devieilhe, Elsa Dreisig’s Elettra, for all her venom and suppressed rage, portrays less of the vengeful fury one usually expects in the role, having little of the vocal vehemence and darkness of such forebears as Júlia Várady or Alexandrina Pendatchanska. This is hardly an accidental choice, nor is it an unwelcome one. Unmistakably youthful and crystalline-toned, her Elettra presents a more human figure: like Ilia and Idamante, she’s another member of the young generation bearing the wounds of their parents’ senseless, bloody conflicts. Her portrayal of the role is as well-drawn in her bitchy asides as through her arias: bitter despair colors Tutte nel cor vi sento, and her final undoing in the excellently executed O smanie! … D’Oreste, d’Aiace scintillates in her terrifying yet futile fury. Between these tempestuous episodes, though, Idol mio comes across as a genuine, thoroughly sympathetic moment of tender pining.

In the thanklessly difficult role of Arbace, Linard Vrielink (another Berlin borrowing) sounds more regal than his king. His throaty but commanding rendition of Se il tuo duol is impressive, though he doesn’t quite manage to make Se colà ne’ fati è scritto seem less superfluous than usual. Allan Clayton’s luxury casting as the Gran Sacerdote offers a glimpse at another potential Idomeneo, while Munich stalwart Tareq Nazmi booms with reliable depth and force as the deus ex machina Voice of the Oracle. The Bavarian Radio Symphony Choir’s members give an outstanding performance, both in the minor solo roles and as a unit, dramatically thrilling and fittingly colorful, vividly depicting the states of awe, joy, and terror in their embodiment of the Cretan populace. After some recent recordings of repertory works that heaved, meandered, and plodded dully along, it’s delightfully refreshing to be able to listen to such a unified level of artistic quality and care.