When Nora Ephron wanted to get the last word on her tumultuous marriage to Carl Bernstein, she wrote the semi-autobiographical novel Heartburn. Sixty years earlier, Richard Strauss did much the same thing with his 1924 opera Intermezzo, which is featured on a new DVD featuring a production from the Deutsche Oper Berlin.

Described as a “ bourgeois comedy with symphonic interludes in two Acts,” Strauss took a major misunderstanding in his own marriage to soprano Pauline de Anha as the basis for his own libretto about the barely fictionalized couple of conductor Robert Storch and his wife Christine.

Christine thinks her husband is having an affair because he receives a love letter that should have been addressed to different conductor named “Stroh.” Meanwhile, Christine becomes friendly with Baron Lummer after they crash into each other. Conveniently, the Baron needs support and is all too eager to assist Christine in her pursuit of a divorce. Christine realizes her husband isn’t having an affair, they quickly reconcile, and her dalliance with the baron is forgotten.

Strauss seems to have written this opera with posterity’s judgement of his wife and marriage in mind. Hofkapellmeister Storch is level-headed and devoted to his wife, son, and music while Christine is mercurial, strong-willed, and taken in all too quickly by the young baron. In the backstage skat game that opens Act II, the other men gossip about how difficult Christine is. Storch defends her by saying they don’t know her and that he needs a fiery partner, but it’s not a passionate defense. At the opera’s very end, Christine suddenly turns tender, apologizes for all the troubles she caused, and asks her husband whether their relationship could be called a truly happy marriage.

The opera ends before he answers, but Strauss has established that he is the model husband and that he is content in his marriage. While the libretto keeps the relationship between Christine and Baron Lummer platonic, the orchestra hints at physical shenanigans. A substantial chunk of the opera’s running time is devoted to orchestral interludes which constitute a set of mini-tone poems on their own. Strauss’s libretto and Strauss’s music don’t always tell the same story, with the music pointing to more turbulence and intrigue than are revealed explicitly in the text.

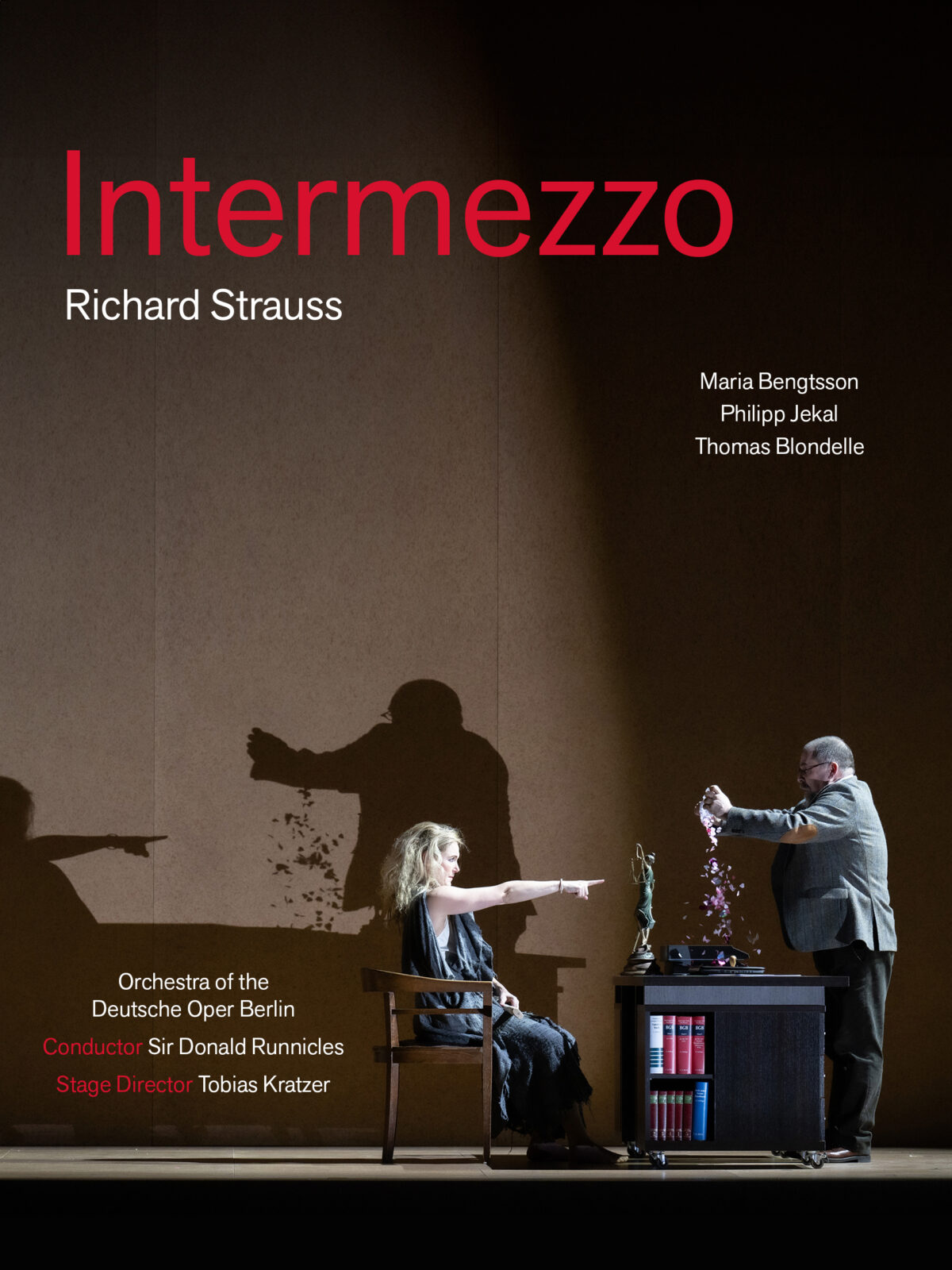

For this excellent production, director Tobias Kratzer digs into the conflicting perspectives and self-referentiality in this surprising work. Kratzer underlines how much Christine is a character that Strauss created for his own purposes. In several scenes she wears an array of costumes for characters from other Strauss operas; videos from Strauss operas play at key dramatic moments. At the opera’s end, Christine sings her reconciliatory lines from a score, because it is so out of character with what came before.

Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Kratzer and video designers Jonas Dahl and Janic Bebi create some stunning videos for the symphonic interludes emphasizing their dramatic and emotional content. In Act II, just before the thunderstorm where Storch learns why his wife thinks him unfaithful, a furious storm blows through the orchestra pit.

Uncharacteristically, Strauss doesn’t give his heroine a chance to soar. Nonetheless, he provided a compelling vehicle for a singing actress who can handle the substantial amount of conversational music with its many changes of tone and mood. Even with occasional moments of hoarseness, Maria Bengtsson is mesmerizing as Christine. She handles the nuances (and micro-agressions) in the music and text flawlessly — a truly impressive performance of a role that must be very challenging to master and perform as well as she does here

Philipp Jekal makes the most of the conductor Storch, but the opera does not paint the character vividly. Thomas Blondelle as Baron Lummer gets more to work with and he captures the bro-coded Baron’s opportunistic oiliness. Nadine Secunde (remember her?) is quite characterful in her brief appearances as the Baron’s landlady. Elliott Woodruff is charming as the couple’s young son Franzl.

Donald Runnicles manages the conversational flow of the music expertly; the symphonic interludes are lovingly shaped and passionately performed. Stefan Woinke designed the atmospheric lighting. Rainer Sellmaier designed the costumes and sets; the latter contain some witty Easter Eggs (Ostrich Eggs?), call-outs to Strauss himself.

This production was the second in a trilogy of Strauss operas directed by Kratzer at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, starting with Arabella and concluding with Die Frau Ohne Schatten, the latter which I hope will be released in due course.

The opera is also available to rent or purchase on Amazon Prime Video.

Heartily recommended. I enjoyed it more each time I watched it.