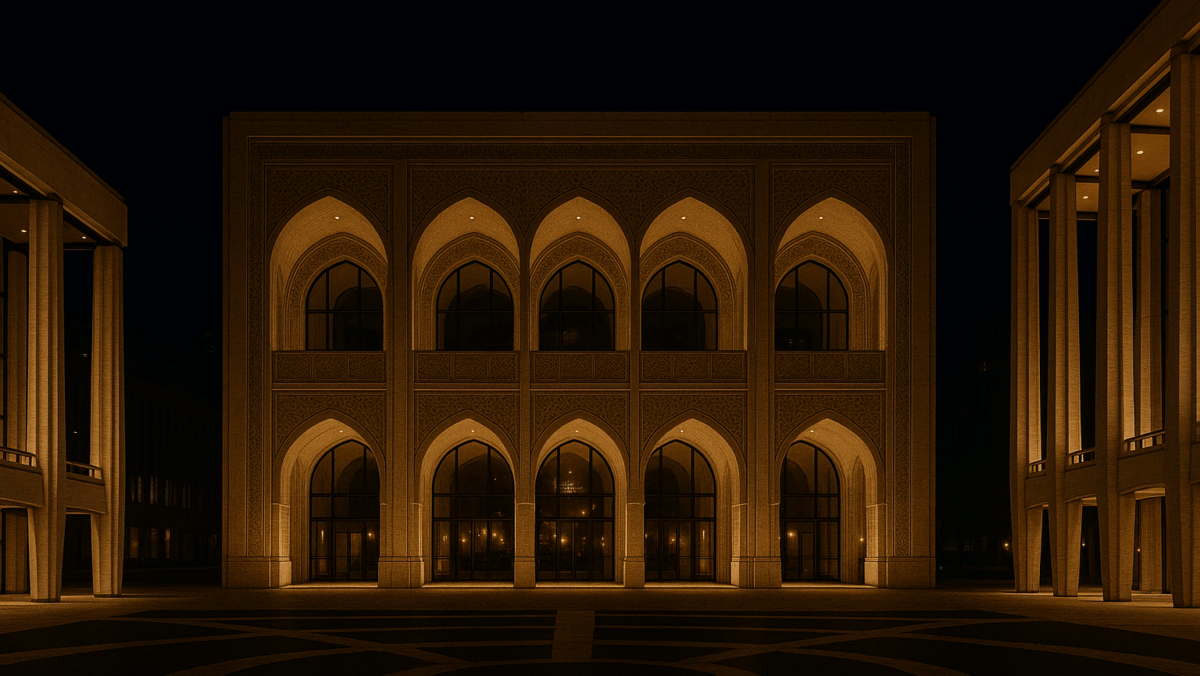

The Metropolitan Opera announced that it has reached an agreement whereby the Met will become the resident winter company of Saudi Arabia’s new Royal Diriyah Opera House upon its completion. The Met also finalized a memo of understanding with the Saudi Music Commission that the Met company will travel to Riyadh each winter for five years to perform fully staged operas and concerts over three-week periods. In exchange, the Met will receive a substantial but undisclosed infusion of cash. Peter Gelb, whose contract has now been extended to 2030 from 2027, noted that this new source of revenue would address the Met’s fiscal woes through 2032.

Not surprisingly, the financial and moral implications of this arrangement has got the comments section at The NY Times boiling over. So, let’s look at this “cultural exchange,” starting with its economic aspects. The Met’s finances have been quite precarious for some time. The Metropolitan Opera raises an extraordinary amount of money each year; according to The New York Times, the Met’s yearly average fundraising haul over the past three years was $174 million. To put this number in perspective, it is more than the total yearly operating budgets of any other performing arts organization in New York City. However, it is barely half of the Met’s yearly operating budget, and still is not enough to cover the gap between revenue and expenses each season. Before the pandemic, the Met needed to implement austerity measures and expand its borrowing, even as its credit rating worsened.

After the pandemic, the budget deficit ballooned, as box office revenue continued to decline while costs increased. In order to balance the books, the Met has had to dip into its endowment every season. This is an extraordinary measure for any non-profit and one that requires approval from New York State regulators. The Times reported that the Met has needed to withdraw $120 million from its endowment since the pandemic–a whopping one third of the total reserve. Given the rate at which the Met is spending down its endowment, the company is only a few years away from a severe financial crisis. So the Met really has just two options to slow the Doomsday clock:

Further cuts to operating costs.

The Met has been cutting back on the overall number of performances and changing the mix of operas each season to reduce overtime and other expenses. While this does lower the overall budget, the fixed costs at the Met are still quite high. The contracts with the unions guarantee payments for a fixed number of “services,” whether they are used or not. I can’t imagine a set of cuts to operating costs that would yield an additional $40+ million in yearly savings without a devastating impact on the season. Even cancelling all new productions would only yield half the savings required, at best. At some point, the season becomes so scaled back that donations start decreasing–accelerating the death spiral. In addition, any cuts to operating expenses arising from changes to the basic parameters of the union contracts would almost certainly result in a protracted strike. Another extended closure would also just hasten the Met’s fiscal collapse. I am not suggesting that the Met union members are overpaid or lodging any criticisms about the contracts; I am simply observing that the Met can’t make major cuts to the cost side of its ledger without necessitating significant changes to its union contracts.

Find another sugar daddy.

It would be nice if the Met could still rely on Bertha Russell to get her husband George to write another big check, but it can’t. And sadly none of the new generation of robber barons appear to have any interest in the Performing Arts. The Met thought they had landed a major new donor, but that tale took a tragic turn. And since we’re not in Finland or France, the government (and this government in particular) isn’t about to provide the needed support.

With no newly minted tech or finance bro here or on the horizon, the Met has had to look elsewhere for the hundreds of millions it so desperately needs. And that is where the Saudi Arabian royal family comes in. They have the funds and are more than willing to spend heavily to bring Saudi Arabia recognition as a world cultural capital while also distracting from stories about oppression or the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

As one of the foremost arts institutions in the US, the Met gets the funds it needs, and its partner gets the imprimatur they seek. But does the “artwashing” undercut the Met’s own principled (and admirable) stands elsewhere, such as its support of Ukraine and against Russian artists who defend Putin? But however the Met may plead that the arts ennoble all humanity — and package this as a grand cultural exchange tied with the ribbon of Condoleezza Rice’s blessing — the moral stench still seeps through. Of the many people I might consult on the ambiguities of dealings in the Middle East, I would not choose someone who received a gift of jewelry valued at over $300,000 from Middle Eastern leaders while in office (even if she was legally barred from keeping them).

I understand why the Met did this. The primary role of the Met’s Board and its General Manager is to keep the organization in a healthy fiscal state. The public disclosures tell us that it is not in good fiscal shape at the moment and I don’t believe we have a full picture of just how troubled the Met’s finances are. I suspect that the Met’s ability to make further withdrawals from its endowment are limited–large donations often come with restrictions limiting their use and preventing their use for general operating expenses. And the Met’s tanking credit rating may further hobble its ability to borrow more money. So, clearly the Met needs financial help.

Also, just like most major donors of the 19th and 20th centuries, any major new donor is likely to bring ethical challenges. Elon Musk? Mark Zuckerberg? Anyone who is actively supporting the current administration, and its war on immigrants, the poor, dissent, the arts, and more? What new sources of funding for the Met don’t have red flags? In my view, we have to accept that the Met needs money and take some comfort that of all the uses for that money, it is, at least, being spent on the arts, and not on gifts for US politicians.

For those of you blaming the Met’s fiscal woes on Gelb’s stewardship, I believe that even if the Met had hired a different General Manager after Volpe, the organization would still be in similar financial circumstances. There is no alternative history where the Met box office remains above 90% of total possible revenue and donations continue to grow. Maybe we would have a less shitty production of La traviata, and maybe we wouldn’t have an expensive “Machine” that is rusting somewhere in the Meadowlands, but the macro trends for performing arts organizations remain the same: attendance and box office revenue are still falling and the Met’s population of major donors is aging quickly. I fear that those trends will likely impact the Met well before this agreement ends — the house needs refurbishing, for example, and even with the Met’s generous new source of cash, the unions will certainly want reconsideration of the cost cutting concessions that they made. As New Yorkers, we have to face the possibilities of a more rapid decline for the company.