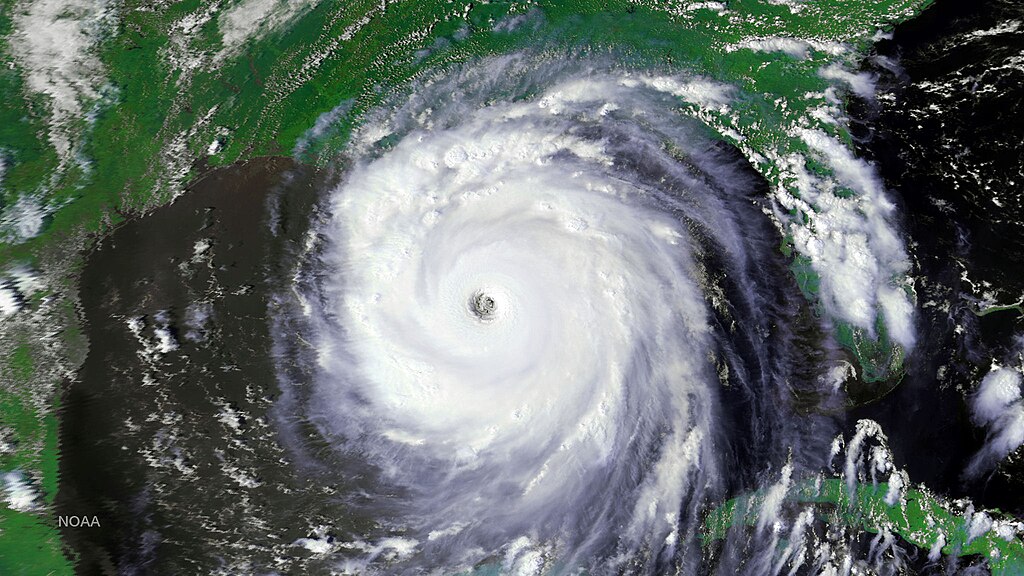

Opera relishes a storm. Find me the librettist who can resist the metaphor of the heart as a tempest-tossed ship or the composer who would pass up the opportunity to show off their chops bringing the swells and gales indoors. Listen to Cecilia Bartoli sing Renoppia from Salieri’s La secchia rapita and hear how thinly she’s disguising her glee at her loss of control as she declares “Son qual lacera tartana” (I’m like a battered fishing boat). She loves the “orrible burrasca,” and so do we. In South Louisiana we throw hurricane parties while awaiting the eyewall’s impact. We do this with affected decadence, an intuition that there’s pleasure to be found in the way stormy weather disrupts reason and order and good sense.

I’ll admit there’s a perversity to beginning these reflections on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina with a discussion of operatic pleasure. Weeks ago I sat in a Mid-City New Orleans cafe with a fellow writer asked to produce a retrospective “explaining” Katrina twenty years out. We commiserated. Who were we to explain? Both of us came to the city as transplants from the region west of New Orleans known as Acadiana – the Cajun homeland of Parterre Box’s founder James Jorden. Also, what more could be said? The tragedies of the Superdome, the rooftops of the Lower Ninth, the nightmare triage in the hospitals, Bay St. Louis in Mississippi looking like Nagasaki 1945 – all these reached us as secondhand news. It’s also hard for me to find anything appealing about redemption arc romances spun out about recovery and rebirth post-Katrina. Every time a documentary filmmaker or a carefully-coiffed anchor on the national news talks about the “resilience” of New Orleans, I go to the dry bar to mix another drink.

So what I can tell you will be idiosyncratic: what I saw and heard in New Orleans before and after the storm, stray musings from a member of the audience with seats quite close to the stage but not the experience of being a participant in the production itself. My recollections of Katrina come with a pair of odd bookends: it starts with Verdi’s Don Carlo and ends with Puccini’s Il trittico.

We left New Orleans in a Chevrolet Venture minivan the Saturday that Mayor Ray Nagin recommended a voluntary evacuation of the city. Freshly sixteen, in the far back seat, equipped with a pocket radio and headphones, I listened to a radio broadcast of Verdi’s Don Carlo, playing with the dial to find the public radio sweet spot anytime the signal crackled. We were on our way back to our bayou hometown of New Iberia from my younger brother’s kiddie triathlon. As the race was still ongoing, crew started dismantling the finish line and directing all participants to the airport or the highways. Traffic crawled. The Infante and the Marquis of Posa declared their manly love for one another. The hurricane evacuation route signs along the roads in South Louisiana suggested drivers tune their radios to a particular frequency for relevant updates. I had mine tuned to NPR.

My reliance on radio for opera access stands out as a feature of that lost pre-streaming, pre-smartphone world. Hundreds of Saturday afternoons I spent with the Metropolitan Opera Broadcasts or, in the off-season, with programs like Lisa Simeone’s World of Opera. The online archive has made it hard to verify which opera was actually playing that Saturday 27 August or even which program would have been airing it. My college students like to repeat their parents’ warning that the Internet is forever, but they’ve yet to watch their pasts disappear behind Error 404s. My memory says Don Carlo, my memory says the five-Act Italian version, and my memory is often wrong and self-justifying and melodramatic as a Tennessee Williams play. What I do know for sure is that in that backseat, as was common in those days, I rawdogged that radio broadcast without a libretto. It was just the backseat of that van, the host’s wry explanation of the plot between Acts, and me with barely enough Italian to navigate a restaurant menu. I might have explained my behavior in the words of Goethe’s Faust: “The feeling is all.”

My memory of the landfall of Katrina itself is almost nonexistent. I remember it being an unremarkable day two hours down the road from New Orleans, not even a day of particularly violent weather. We were west of the storm, the side of the spiral that Gulf Coasters will refer to as “the good side.” Katrina came to us in New Iberia as carloads of refugees, silent and shellshocked new classmates in the desks next to us, and interminable rumor and conjecture.

Two years later I was in college at LSU attending as many nearby opera performances as I could. The pleasures of being a big Southern state school kid ferreting out art wherever he can find it cannot be overstated. You haven’t lived until you’ve heard Britten’s The Rape of Lucretia performed in a venue called Swine Palace where livestock judges in the old days used to decide which of the pigs was the prize one. For my eighteenth birthday, my parents gave me tickets to the 2007-08 season of the New Orleans Opera Association, an organization one letter off in its acronym from the hurricane-tracking National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Solo, I’d drive down I-10 from Baton Rouge to New Orleans on Sunday afternoons to catch the matinées.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Carol M. Highsmith [LC-DIG-highsm-04024]

By this point the media and politicians might have told you that New Orleans had “recovered” from Katrina, but the NOOA was still in exile at a Tulane campus auditorium and had not yet returned to the Mahalia Jackson Theater downtown. The Mahalia had taken on 14 feet of water and was not in any shape to stage anything. Walking through Uptown neighborhoods, one could still find “Looters will be shot” in big capital letters on wooden fences. Even the Katrina crosses were still a common sight in 2007 – those spray-painted St. Andrew’s Xs on the sides of homes with codes in each quadrant indicating which disaster response team had cleared the house, on what date, what hazards lurked inside, and how many dead bodies had been found there. Even now, in 2025, I’ll occasionally get jumpscared by one when my citywide strolls take me down an unfamiliar block.

Going to the opera alone at eighteen means that you will often be adopted by your older seat neighbors – frizzy-haired eccentrics, soft-spoken retiree couples, perhaps an effete and balding bachelor aesthete who sees, in you, the ghost of his younger self. The November weekend I drove down to see the 2007 production of Puccini’s Il trittico, my opera guardian for the afternoon came straight out of central casting – a tall, older Italian man with fists full of heavy gold rings, the kind of guy who had a seat in the back room of the New Orleans bar where the Marcellos planned the Kennedy hit. We chatted briefly and settled in to enjoy.

Conducted by Robert Lyall and directed by Jay Jackson, this Il trittico was the kind of staging critics might breezily call “a love letter to the city of New Orleans,” with each one-act reimagined in a New Orleans setting: a barge on the Mississippi riverfront for Il tabarro, the Ursuline Convent for Suor Angelica, the Pontalba Apartments on Jackson Square for Gianni Schicchi. The English supertitles had been adjusted to reflect the geographic shift, and the audience chuckled knowingly at the local references with those little not-quite-laughs of recognition that people like to do at the opera. What could have simply been a kind of picture-perfect salute to New Orleans, however, became a stranger and more textured aesthetic experience as the post-Katrina moment recontextualized elements of the opera in not-always-comfortable ways.

When Il tabarro settles down after the winking, fourth-wall-breaking joke of the Mimì song and the character pieces like Frugola’s ode to the goodies in her bag (in this production all manner of Mardi Gras parade catches), we arrive at the Belleville duet. Giorgetta and her husband’s stevedore Luigi bond over their youth in the Parisian suburbs, reminiscing over trips out to the Bois de Boulogne and the familial camaraderie of neighborhood life. The music soars beyond the rather mundane details of lit-up shops and sounds of feet on paving stones. The vocal line, its intensity bordering on spiritual ecstasy, signals to us that we’re way beyond home here as a set of quaint bits of French local color. We’re talking home as pure transcendental form. The capital H concept of Home. As with all transcendental philosophizing, though, you eventually hit the wall of what you can possibly explain in language. Even Giorgetta admits as much: “È difficile dire cosa sia quest’ansia, questa strana nostalgia!” (It’s difficult to say what it is, this anxiety, this strange nostalgia).

All of this could be used to affirm a kind of uncomplicated affection for home and returning there, though Giorgetta’s ansia and her sense of her nostalgia as strana, leads us into the complicated ways New Orleanians post-Katrina were thinking about their homes and their possible homecomings. Giorgetta and Luigi sing, “Ma chi lascia il sobborgo vuol tornare e chi ritorna non si può staccare,” and this seems to pair well with the romantic narratives of post-Katrina return often circulated by the national media. It does not harmonize, however, with the realities of families displaced to Houston or Atlanta who looked back at New Orleans with more muted, though indeed still strange, nostalgia. While it doesn’t make for feel-good inspirational stories, the truth is that a number of former New Orleanians found their exile a chance to start over in a space of greater stability. (Read Sarah M. Broom’s memoir The Yellow House for an artful expression of this ambivalence about post-Katrina return.) Giorgetta’s other line in the Belleville duet – “Noi non possiamo vivere sull’acqua” (We cannot live on the water) – echoes somberly in New Orleans, with its proximity to an eroding coastline, its neighborhood streets that flood in thunderstorms, its French Quarter where one must sometimes look up out of the bowl of the city to see barges passing on the river overhead.

For myself and for others, though, Giorgetta and Luigi’s breathless praise for Belleville feels like what we feel about New Orleans. “L’aria di Parigi m’esalta e mi nutrisce,” Giorgetta explains – and I could say the same of the humid, jasmine-and-sewage-scented air of a New Orleans summer. It excites me and nourishes me.

Opera allows us to be both home and afar. I remember as a teenager, for the first time, hearing a word resembling hurricane while listening to Herbert von Karajan’s 1961 recording of Verdi’s Otello. Mario Del Monaco, every inch the Venetian lion, exults in his military triumph: “Dopo l’armi lo vinse l’uragano!” I turned the word over in my mouth – uragano. It did not taste baroque and curlicued like the other Italian go-to tempeste or languid like the French orage. It had a familiar swirl on it to my Louisiana tongue. Its origins go back into Spanish and from there back again into Taino. It’s a Gulf of Mexico word Otello cheers. Like Giorgetta’s nostalgia for the Paris that fills her with exultation, it sounded like home.

Then, Suor Angelica. Here, unapologetically, we have a reminder of the truth that Catholicism is the opera of religions, and opera is the Catholicism of the arts. Extravagance and bigness, a canvas large as the cosmos, the despair of mortal sin and the ecstasy of miraculous salvation. Back in my hometown of New Iberia, stories of Marian miracles and crying statues enjoyed extensive popularity among the Cajun faithful. As a teenager I resented the superstitions, but it’s hard to watch Suor Angelica and not understand why people enjoy the marvels and the visions so much. I cry. You cry. The Virgin Mary cries. It’s all such campy fun. There’s a kind of aesthetic maximalism to it all, a maximalism that also characterizes New Orleans – a city rarely described as understated, minimalist, or even tasteful. The old Italian man with the chunky rings sitting next to me was sobbing by the end of it. Of course, “Senza mamma” had been too much for him. He apologized. He leaned over to me: “After that, we’ll all need something funny.”

The Gianni Schicchi stands out in my memory most vividly, with members of the Donati family shuffling around Buoso’s French Quarter apartment in costumes self-consciously referencing Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The silliness stopped for a moment, though, for Rinuccio’s “Firenze è come un albero fiorito.” It emerges at the center of the opera like poetry from the Book of Psalms – the city as a flowering tree. Just as passionately here as in the Belleville duet, we hear the city extolled as the site of human flourishing. As tenor Bryan Hymel, a native son, waved the flag of New Orleans over the stage, it seemed at first pure triumphant post-Katrina spectacle. We were back, fleurs-de-lys and Saints football and second lines and all.

Yet here, as in Il tabarro, a wrinkle. Rinuccio’s aria praises “la gente nuova,” the newcomers to Florence who will contribute to its scientific and artistic successes. In the Tulane theater that afternoon sat native New Orleanians who use the word transplant like a slur, uttering it with the same bile Zita Donati injects into the phrase gente nuova. Especially after Katrina, the city’s centuries-long suspicion of newcomers became entangled with national conversations about gentrification and who has a right to claim which spaces as home. Even now, as an acknowledged member of la gente nuova, when someone here asks where I’m from, I identify myself as a New Iberian who has lived in New Orleans seven years. But go ask Rinuccio. He’ll vouch for me.

Writing this piece after returning to New Orleans from a week in Paris – including a trip to the Bois de Boulogne – I keep turning over in my mind Giorgetta’s warning from her barge on the Seine that we’re not meant to live on water. Throughout Paris I noticed on public buildings the city’s bland, modern rendering of its old coat of arms, a ship at sea. The corporate minimalist ship lacks the Latin motto that should go with it: Fluctuat nec mergitur. She is tossed by the waves but does not sink. When the curious ask why I live in New Orleans despite the collapsing infrastructure, the floods, the running catalogue of impracticalities, I’m tempted to answer a bit too cheekily that in an era of optimization and streamlining, there’s a pleasure in being tossed about by chance, fortune, grace, the weather itself. That answer, though, is insufficient and waggish and too tidy by far. With Giorgetta I might also answer when asked why I love New Orleans or why I love opera: “È difficile dire cosa sia.” It’s difficult to say what it is.