We live in a world. And in that world, sopranos and tenors get all the shine, and lower voices are now relegated to sub-prime status—tolerated and if considered at all, treated like canopic jars, the viscera of their musical function excised and held separate from what was formerly a complex, living apparatus of psycho-social-vocal texture.

The expectations for voices became so dictated by studios that in the second half of the 20th century, I believe we largely lost cultural memory of what those voices can and should sound like, their timbres, their possibilities—not just as singular artists or in particular roles but how those personages and voice types dovetail into a larger framework.

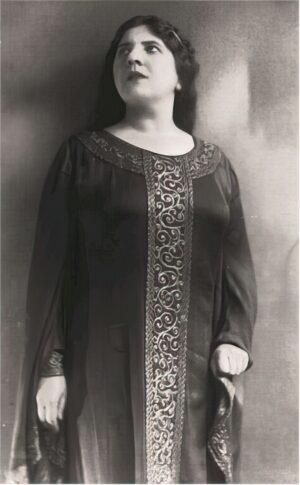

Few singers caused in me such an immediate break with notions I formerly held about mezzo-contraltos than one of whom we have fairly few recordings—the Galician-born Polish-Jewish contralto Sabine Kalter.

I first heard her in a 1925 acoustic recording of “Gerechter Gott” from Rienzi on the early internet treasure trove Cantabile Subito. The piece itself is all but forgotten now, but Kalter’s reading of it makes it serious, important, almost like a missing standard for a voice type that in general has too few greatest hits.

I find her particular mix of immediacy and urgency with a tone that is both frank and mellow particularly beguiling. Many years ago I’d grown accustomed to—maybe even expected—some measure of thickness and hootiness in a contralto. I always imagined the words to have been lost spelunking in a cavern of molasses, an asphyxiated echo desperate for recognition and rescue.

With Kalter, though, the mellowness is in the tone itself, and the clarity of the vowel rides right on top of it. Her facility with the gruppetti and rapid scales—figures we don’t really associate with Wagner—is impressively integrated. No clicks or clucks or aspiration. Pure pitch, pure tone, pure note value. In this way she resembles Sigrid Onegin, with perhaps more warmth, less distance.

But only a couple years ago, I came across a 1936 live Tristan und Isolde from Covent Garden whose cast—led by Flagstad and Melchior!—included Sabine Kalter. And in act II, it captures her in the most exquisite, most otherworldly performance of Bragäne’s Watch (“Einsam Wachend in der Nacht”) on record.

The voice is not lightened and suppressed in order to make it seem ethereal or floaty. It is a pearlescent castle wall dug firmly and deeply, reflecting the elements, establishing a perimeter that is impenetrable because it is endless. To sing with this kind of fullness and definition, making the voice both celestial and chthonic, is a matter of technique, yes, but one that depends primarily on a particular mental model, a spiritual model of sound and word, a soul’s image in the ear.

This kind of singing isn’t a matter of holding your breath, crossing your fingers, and meting out a thread of sound at all costs. Rather it’s about getting completely out of the way, allowing nature to inhabit you and the sound to inhabit the theater, all of which become synchronized, breathing and resonating in total unity.

In listening to this clip, you get that sense that the voice and music and text were always one, that the sound was always there, complete and constantly emanating from the place that’s the source of all perfect things.

For this brief moment we and Kalter are merely tuned into that divine station, suspended together in the night.

| BRANGÄNES STIMME (von der Zinne her) Einsam wachend in der Nacht, wem der Traum der Liebe lacht, hab der einen Ruf in acht, die den Schläfern Schlimmes ahnt, bange zum Erwachen mahnt. Habet acht! Habet acht! Bald entweicht die Nacht. | THE VOICE OF BRANGAENE (from the parapet) You upon whom love’s dream smiles, take heed of the voice of one keeping solitary watch at night, foreseeing evil for the sleepers, anxiously urging you to waken. Beware! Beware! Night soon melts away |