Courtesy of the Fisher Center at Bard College

The Summerscape Festival at Bard College is always a highlight of midsummer. Leon Botstein, president of Bard and director of the American Symphony Orchestra—an organization with a special taste for valuable but obscure repertory—chooses each year a composer whose personality, and that of his intellectual circle, are worthy of exploration and then, a bit perversely, picks an unusual grand opera by not that composer but one of those connected to his movement, and stages it in the Frank Gehry-designed Sosnoff Theater of Bard’s splendid Hudson River campus.

This year, the composer at the center of the festival is Bohuslav Martinů, a Czech modernist who left home for Paris in 1923 (what composer didn’t run away to Paris then, if they could?) and later, when war threatened the Parisian scene, on to the United States. His later years were divided among his three countries, and he remained, though never a popular taste, prolific and respected until his death in 1959. There will be conferences in August around Martinů and the movements he related to, climaxing with a concert presentation of Julieta, his surreal opera of 1936.

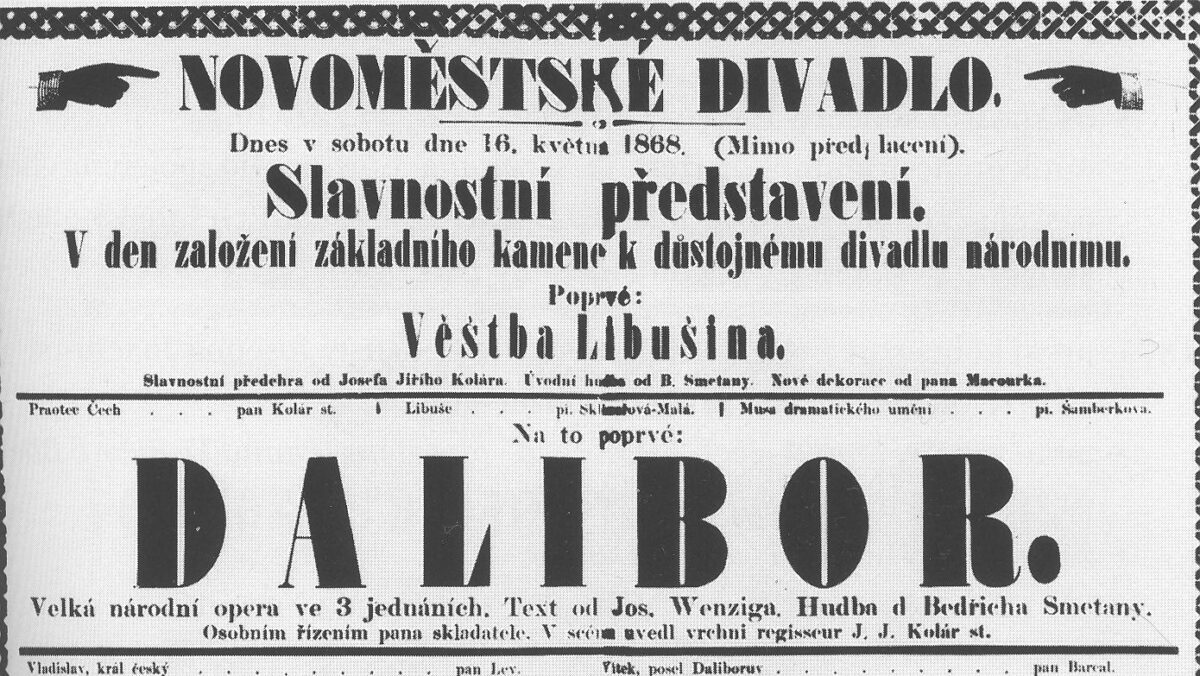

But that means the centerpiece of the festival must be the work of some related composer, and Botstein’s selection, curiously, is his compatriot Bedṙich Smetana’s Dalibor, which had its premiere in Prague in 1868, failed, was revised a bit, but did not enter the popular repertory—and only in the kingdom of Bohemia—until after the composer’s death.

“It’s difficult to find an opera that fits the tradition of the Festival,” Botstein explained to me. “A work little known but worthy, with the full grand opera apparatus.” He has presented other Czech works—Janácek’s Osud and Dvorák’s Dmitry—and they too required full choruses and a large orchestra. “You can’t risk a purely academic work,” he muses. “Theatricality is important. Dalibor has the rescue plot, the patriot imprisoned, the woman who disguises herself as a man to get him out—people who know Fidelio are a step towards understanding what is going on.”

Bedrich Smetana

Dalibor marks a conjunction of two popular varieties of opera: the rescue opera—an eighteenth-century standby—and the opera of nationalistic fable, something like a theatrical anthem, that came into fashion in the age following the French Revolution. For the Czechs, who were establishing themselves after centuries of German cultural colonialism, the intrinsically musical character of Czech culture called for celebration and works in the national register.

The rescue trope had a long tradition. You could say it was invented by Euripides with Helen in Egypt and Iphigenia in Taurus, in both of which Greek princesses are rescued from barbarian kings in the nick of time. The tension of threat and escape was a gift to playwrights and composers, not to mention actors.

Suspenseful Iphigenia inspired dozens of operas; thirty composers set the tale, Gluck, nearly the last, being the most famous. Dalibor is unusual in that it raises our expectations of escape and then doesn’t give it to us. The hero’s patriotic frustration may have something to do with Smetana’s hopes for the revival of Bohemia, which was going through a rebirth at this time.

Smetana was born near Prague in 1828 and became a virtuoso pianist, though it was a long time before his ability as a composer manifested. Meanwhile, he accepted a conducting post in Sweden, where the chilly climate killed his wife and piano partner. When he returned to Prague, it was to a lively controversy in that multi-ethnic city over whether theater (and opera) should be given in German or in Czech, and whether local Czech composers or Italians in translation should make up the operatic repertory. Similar linguistic disputes were going on at that time in Norway, Ireland, Croatia, Catalonia and Ukraine, but the Czechs focused on the musical message.

After the Revolutionary era, the popular audience (and opera was a popular art form) ceased to care about mythical heroes and became more interested in national figures inspiring national events. If you couldn’t cheer for your oppressed nation in the streets or in the press, you could cheer for it on stage and hum tunes in the local dance rhythms. In Bohemia that meant the polka. Smetana filled his operas with polkas, though he did not borrow folk tunes but invented them himself.

In Prague, German had long been the language of the elite, and therefore of opera. (In Mozart’s day, there had also been a court opera that, like the court opera in Vienna, sang in Italian.) Smetana joined the agitation for a national opera and hoped for a position as its conductor, though the few Czech works available tended to be of an unsophisticated ballad-opera variety. Eventually a “Provisional Theater,” performing operas in Czech, opened in 1862, and though its conductor preferred translating Rossini and Verdi, Smetana was able to secure a commission for his first stage work, Brandenburgers in Bohemia, a mild success in the style of Meyerbeer.

In 1866, he produced Prodana Nevesta, The Bartered Bride, his greatest triumph. Ironically, this comedy, though filled with polkas in the rural Bohemian manner, was not intended to be the national opera—its lively antics lack the grandeur Smetana felt was called for. And yet Bartered Bride and his tone poem, Ma Vlast (or at least The Moldau), became his most beloved works, the emblems of Czech culture around the world.

Bartered Bride owed its success, in part, to its lightness. To translate a comic opera to get laughs was not seen as violating national sanctity. Like the comic operas of Mozart, Rossini, Donizetti and Offenbach, Bride could be performed in any convenient local tongue.

Like Smetana, his preferred librettist, Josef Wenzig, was a German-speaking Czech who preferred to write verses in German. The two operas he wrote for Smetana, Dalibor and Libuse, were painstakingly reworked into Czech verse by the poet Ervin Spindler, with word-choices that made it possible to sing the same music in either language. Singers have found the Czech stresses and word-choices awkward—they come across as “libretto-ese” to Czechs familiar with the later operas of Dvorak, Fibich and Janacek. This was an issue in Prague when the speakers of German and those of Czech were contending for national symbolism.

But this was not Wenzig’s only problem. He lacked the gift for dramatic power, for building a scene into a theatrical action. There are few moments in Dalibor that wake you up, make you eager for the next encounter. The characters sing together but do not confront each other. The richness of Dalibor’s melodies does not expand into sweeping, swift-moving scenes.

But the theme of the noble-minded prisoner suits a national message. The opera opens with a trial scene—trials make great theater, civic rituals that an audience can understand. A certain Milada appears at the court of King Vladislas to demand the death of Dalibor for slaying her brother, a royal official, and Vladislas responds with a defense of feudal law and order. (As the Czechs remembered, if no one else does, Vladislas was a foreign, Polish prince elected to the Bohemian throne.)

Then Dalibor enters to defend himself—he was avenging his beloved friend, the musician Zdenek—and he sings so nobly that Milada falls in love on the spot, though she and Dalibor have never met. She then disguises herself as a boy and gets a job with Benes, Dalibor’s jailkeeper—just as in Fidelio.

We are on tenterhooks for the next scene or two—will the jailor give Dalibor the violin he has asked for, and will the disguised Milada be able to use that excuse to get in to see him, declare her love and plan an escape? We know the answer, but there is dramatic tension (and some very pretty tunes) while we watch it unfold. Also there is the ghostly visitation (a violin solo) from Dalibor’s beloved Zdenek to cheer him up.

In Prague, by the way, Zdenek’s Violin is sometimes said to be a nickname for a medieval engine of torture applied to the shoulders. Supposedly, a prisoner confined in what is now called Dalibor’s Tower sang to the violin—or howled in agony—and his cries, heard by passers-by (who tossed him their spare change), were called “the song of Dalibor.”

Details of the folk tale are imprecise, but in the opera, the violin becomes an actual musical instrument, played from the next world by the spirit of Zdenek. From the agonized cries of a condemned prisoner to the amorous despairs of a lonely tenor is not much of a jump for an opera story. Meanwhile, Milada, disguised but permitted a brief love duet with the prisoner, makes use of an actual violin to soothe the jailors into letting her visit him. Dalibor is supposed to play this to summon help for his jailbreak—except that a string breaks at the climactic moment, which Dalibor correctly interprets as a bad omen. Everybody dies, interrupted by attractive chorales. King Vladislas gets another handsome aria, perhaps because Smetana was courting the favor of Franz Josef, the king’s direct descendant.

Dalibor was not a hit at its first hearing, in 1868. For one thing, at a time when national schools were in conflict, many a local patriot thought Smetana’s through-composed melodies, gliding into one another with little break, savored of the hifalutin style of Richard Wagner. Wagner was certainly at the forefront of modern music in the 1860s, and his influence on such Bohemian-born composers as Dvorak and Mahler is indisputable, but he was utterly, passionately German. All this interfered with the acceptance of Dalibor as a national symbol.

Conductor Leon Botstein (Ric Kallaher)

Smetana, who became deaf in the 1870s and then mad in the ‘80s, did not live to see this work become popular. But from its first revival in 1886, two years after the composer’s death, Dalibor entered the Bohemian repertory, achieving its 300th Prague performance by 1914. Meanwhile Smetana had composed the even statelier Libuse, on an even more static Wenzig libretto, from the legend of the pagan prophetess who founded Prague and its first reigning house.

“Dalibor has an unusual performance history,” Botstein told me, explaining its selection. “Mahler gave the first Vienna performance,” in German in 1897. The opera was then translated into many Slavic languages, but became a favorite only at home. “I considered staging Libuse, but Dalibor is less crudely nationalistic. Too, the opera is through-composed—no spoken dialogue. And it became a popular favorite among the Czech-speaking audience, despite Smetana’s poor command of Czech. Communist Czechoslovakia liked him too, and they were not great admirers of Dvorak or Martinů. Smetana was admired for his craft by Heinrich Schenker, the theorist and critic in Vienna in the early twentieth century, who considered himself a classicist and was rabidly anti-Mahler.” So Dalibor was a favorite with both Mahler and his nemesis.

Dalibor will be given five performances between July 25 and August 3 at the Sosnoff Theater, fully staged by Jean-Romain Vesperini, who staged Saint-Saens’s Henry VIII there in 2023, performed by the American Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leon Botstein.