I refer to Sabine Devieilhe and Lise Davidsen’s appearances at the Munich Opera Festival, where they starred as the titular waif in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Liza in Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame, respectively. Devieilhe, a clarion coloratura, has proven peerless in her interpretations of the French Baroque repertoire, Romantic lieder, mélodie, and much in between. Her approach to any repertoire is always idiomatic, and her pristine musicianship captivates. On the other side of the vocal spectrum, Davidsen’s refulgent lyric dramatic soprano has made her today’s leading exponent of Strauss and Wagner. Her recent appearances in New York have also allowed audiences to appreciate the depth of her artistry. These two artists possess vastly different instruments, to be sure, but they both proved luminous presences across two darkly atmospheric productions.

Dutch director Jetske Mijnssen, making her Bayerische Staatsoper debut in this production at the more intimate Prinzregentheater, moved Pelléas et Mélisande away from the medieval realm of Allemonde and into a late-Victorian domestic setting. It is almost de rigeur among directors to shift Pelléas to the time of composition—Graham Vick’s 1999 Glyndebourne production being a notable example—but Mijnssen’s dynamic blocking along with Ariane Bliss’s clever dramaturgical interventions made the concept feel fresh.

In the opening scene, Golaud finds himself not lost among the boughs of an ancient forest, but pacing around an elegant ballroom as couples waltz around him. He finds his footing, if only for a moment, in the presence of an equally anxious Mélisande. Set designer Ben Baur’s stark arrangements of Biedermeier furniture upon parquet flooring supplant the decaying castle halls of the subsequent acts. A shallow trench of water along the stage’s edge stood in for the Blind Man’s Well, providing the characters with their sole means of communing with the natural world amid their stifling bourgeois surroundings.

Yet despite forgoing the work’s fairytale aspects, Mijnssen’s approach retained a sense of the faraway, the unreal encroaching upon what once seemed solid and true. We watched as a collective erotic haze descended upon an already ailing family unit, challenging their rigid notions of propriety and engendering, or perhaps revealing, the violence among its ranks. It was raw, sensual, and unsettling—one of the strongest productions of an opera I have seen in a while. The production will appear at The Dallas Opera in November. Do not hesitate to attend if you are able.

Devielhe’s Mélisande was a wonder. Her voice had a gossamer feel while its essential brightness, which never veered into harshness, ensured that it could pierce through Hannu Lintu’s plush, if occasionally opaque, conducting. She often eased into the notes, subtly building the intensity of her vocal lines to exude an expansive quality. Her “Mes longs cheveux descendent” had an unearthly aura, pouring into the hall in a cascade of violet-hued sound. Yet, in keeping with the production’s more grounded elements, she infused a spirited determination into her interpretation of the heroine. She sang with a self-assured abandon as she teetered on the well’s edge, and her voice took on a slightly steely edge as she faced Golaud’s interrogation over her missing wedding ring.

It is hard to believe that Christian Gerhaher was once a Pelléas, given how well the role of the elder brother suited his full-bodied baritone. As Golaud, he gave the most dramatically compelling performance of the evening, conveying a man riven by his increasing paranoia and inclination towards rage. The scene in which he forces little Yniold, sung with poise by Tölzer Knabenchor member Henrik Brandstetter, to spy on the would-be lovers was unnerving, as each command he bellowed at his child chipped away at any semblance of decorum. His intensity melted into pathetic self-loathing in the final act, and he infused a tenderness into his pleas for forgiveness that stirred the audience’s empathy.

Tenor Ben Bliss delivered a similarly strong performance as he traced Pelléas’s arc from a good-natured if occasionally negligent lad to a man completely consumed by an obsessive passion. His bright, vigorous top delivered some moments of sheer beauty, though his lower register often got lost amid the thicker orchestral passages. There was a considerable amount of heat in his interactions with Devielhe, especially in the rather voyeuristic rendering of the Tower Scene, and the two sold their characters’ bourgeoning attraction well. Bass Franz-Josef Selig was commanding as the patriarch Arkel, while mezzo-soprano Sophie Koch brought a matronly warmth to Geneviève.

Pique Dame was more of a mixed bag. The production by Australian director Benedict Andrews, which premiered at the Staatsoper’s Nationaltheater last February, is set in a nebulous contemporary setting: vaguely retro yet forgoing any dalliances with Soviet-style aesthetics for generic cool. Instead, Andrews adopted the aesthetics of the uncanny to bring us into Herman’s experience of alienation. The chorus emerged as an ominous, blank-faced entity from the back of the stage through John Clark’s smoky lighting to descend upon Herman, who was often situated by the prompter’s box. During the ball scene in Act II, the chorus and many of the principal characters donned plastic masks that blurred their features as they robotically danced in unison among a set of bleachers. Herman’s fellow officers, Tsurin and Chekalinsky, played with thuggish glee by bass Bálint Szabó and tenor Kevin Connors respectively, seemed hellbent on torturing their supposed friend at every opportunity, as were the children’s chorus in the opening scene and nearly every other character other than Liza. There were also the usual directorial flourishes: long drags of cigarettes, strippers, doubles, moody projections between the scenes, and an assortment of vehicles rolling onto the stage.

If the production largely succeeded in its exploration of self-estrangement, it was in large part due to the presence of tenor Brandon Jovanovich as Herman, reprising the role from the winter run. His Herman appeared incapable of behaving normally; he staggered around the edge of the stage, gangly and wild-eyed, brandishing his pistol in the audience’s direction. He often mimicked the behavior of those around him, as when he mirrored the Countess as she caressed herself in her boudoir and contorted his face into a painful, Looney Tunes grin amid the general merriment at the ball.

His efforts to conform merely exacerbated his isolation and drove him closer to the brink. It was a deeply committed performance that brought many of the production’s more original ideas into relief. Musically, he was less consistent. His tenor combines a mellifluous, smooth tone with ample heft along his middle range, setting him apart from the darker voices that have tackled this notoriously tricky role. Yet he approached many of the role’s punishing upward leaps with hesitancy, delaying his vocal production at times and resulting in a few cracks and an aborted high B at the end of the first scene. However, he gained momentum as the evening progressed.

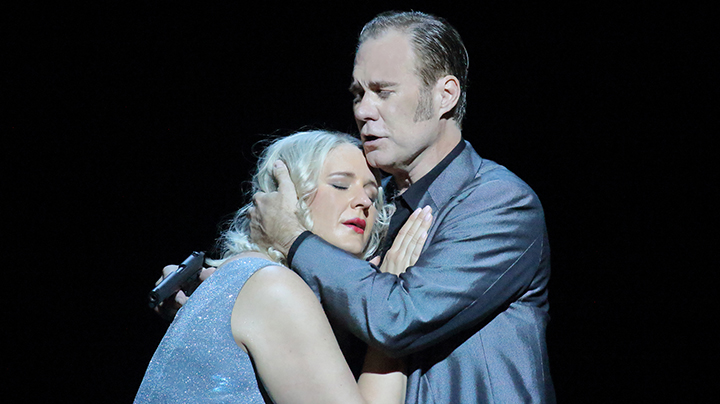

As Liza, Davidsen was one of the few new additions to the production, replacing Asmik Grigorian from the original lineup. Likely due to a lack of rehearsal time, she was somewhat ill at ease with the blocking, not quite conveying the disaffected, moody heroine the production demanded. Still, her singing was gorgeous throughout. She scaled back her instrument significantly during her duet with Victoria Karkacheva’s plummy Polina, as the two women’s voices rippled in and out of each other’s. Her Act III arioso “Akh! istomilas ya goryem” contained a range of dynamic colors. In the first half of the piece, she suspended her sound at a silver-cast mezzo piano before sighing into a diminuendo, imparting a rather spectral air. Her high notes ignited her final duet with Herman—the love story was perhaps the weakest aspect of the production—and she left us with a coruscating F sharp that sliced through the orchestra.

Violeta Urmana appeared as the Countess in full 80s-era Elizabeth Taylor drag. Her mezzo-soprano retains much of its distinctive coloring, even if the sound is not quite as plush as it once was. There was a decrepit sumptuousness to her Act II aria “Je crains de lui parler la nuit.” As Prince Yeletsky, Boris Pinkhasovich garnered the most enthusiastic applause of the evening for his elegant and deeply felt “Ya vas lyublyu,” during which his mulberry shaded baritone unfurled some lovely legato lines and revealed a well-developed upper register. Baritone Roman Burdenko brought a rakish energy and a superb handling of the text to Tomsky’s two arias. Natalie Lewis and Daria Proszek impressed in their brief appearances as the Governess and Masha, respectively.

The fine quality of much of the singing was undercut by conductor Aziz Shokhakimov’s lackluster performance in the pit, which saw numerous coordination issues throughout the evening as well as general lack of shaping; the very fine Bayerische Staatsorchester sounded near cacophonous at points. The issues in the pit became most apparent during the piece’s many choral sections, and he was unable to effectively sync the orchestra with the Chorus of the Bayerische Staatsoper. Only in the a cappella final prayer were we able to appreciate the richness of the chorus’s sound.

Photos: Wilfried Hoesl