Orlando Figes, in his magisterial history The Europeans, described Giacomo Meyerbeer as “the first great composer of Grand Opera” and an enterprising artist who “embraced the industrial age”—fitting characterizations for a musician whose lavish and technologically spectacular blockbusters dominated the Parisian scene for the greater part of the 19thcentury. His compositions, an eclectic amalgam of “German harmony, French rhythm and orchestration, and the Italian bel canto style,” became vehicles for sensational melodramas that embodied the template for artistic success at Paris’s prestigious Académie Royal de Musique. Meyerbeer’s sprawling creations for the French stage propelled his status to great celebrity and became the most frequently staged works at the world’s leading opera houses during his lifetime.

Today, Meyerbeer’s operas have become largely relegated to footnotes in the performing canon—a fate that can be partially attributed to the staggering expenses required to mount his works, as well as the extraordinary caliber of vocal music he demanded from his soloists. Meyerbeer’s reputation as a dramatist has also diminished in some circles, with some criticizing his emphasis on theatrical spectacle and visual opulence as compensating for the inconsistent dramatic tension and paper-doll-like characterization found in his plots and orchestration.

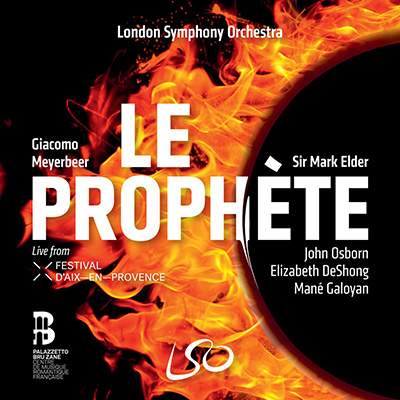

While these criticisms can be valid for Meyerbeer’s earlier works, his more mature operas like Les Huguenots and Le Prophète integrate his keen vision for extravagant theater into coherent and even powerful narratives that justify his importance as a figure in opera. A compelling new recording of Le Prophète, recorded during a concert performance with Mark Elder and the London Symphony Orchestra from 2023’s Aix-en-Provence Festival, makes a persuasive case for a reappraisal of one of Meyerbeer’s most significant contributions to the art form.

In Le Prophète, Meyerbeer and his librettist Eugène Scribe portray a gripping melodrama that explores the perils of religious fanaticism and political ambition. Inspired by the historical Westphalian rebellion that occurred during the 16thcentury, Scribe’s narrative centers around Jean de Leyde, a humble Dutch innkeeper who becomes entangled in a political uprising orchestrated by a group of Anabaptists. Jean’s crusade gains momentum when he is crowned as the Anabaptist’s prophet, and his followers establish a theocratic community in the town of Münster.

Intoxicated by his newfound authority and consumed by religious delusions, Jean becomes a zealous theocrat, his moral compass wavering until the final act’s militaristic confrontations. It is only through the intervention of his mother Fidès that Jean recognizes the errors of his ways and seeks redemption. In a climactic act of retribution against the corrupt political establishment and the traitorous Anabaptists, Jean lures his enemies into the palace of Münster, which he engulfs in a fierce conflagration that brings about their collective destruction.

Le Prophète, like much of Meyerbeer’s work for the Paris Opera, is a colossal undertaking that dazzled audiences with its exuberant ballets, awe-inspiring technical effects, extravagant orchestration, and monumental choruses. Amid this grandeur however, the opera’s emotional core lies in Jean de Leyde’s relationships, particularly with his beloved Berthe and, most crucially, with his mother Fidès. Although the opera bears Jean’s name, it is Fidès who serves as the linchpin upon which the work’s tragic power hinges, undoubtedly a result of Meyerbeer’s collaboration with the legendary mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot.

The opera may abound in large set pieces that showcase Meyerbeer’s mastery over marshalling the totality of the opera’s forces, but its most poignant moments are rooted in the profoundly human interactions between Jean and Fidès. It is through these characters that the opera’s exploration of religious fanaticism finds its resolution, as Jean’s redemption and ultimate sacrifice are guided by the unwavering love and moral fortitude of his mother.

Mark Elder’s new recording of Le Prophète sets a new standard for this monumental work, surpassing the only two previous official recordings in the discography in terms of its musicality and the strength of its casting. The first, conducted by Henry Lewis nearly half a century ago, remains noteworthy for Marilyn Horne‘s legendary portrayal of Fidès, whereas the second from 2017, using the critical edition of the score, was assembled from a run of performances in Essen. Elder’s remarkably balanced and detailed interpretation, brilliantly executed by the virtuosic London Symphony Orchestra and the excellent Orchestre des Jeunes de la Méditerranée, benefits from the conductor’s extensive exploration of a breadth of 19th century operas, ranging from the more popular works by Wagner and Verdi to rarities by Rossini, Gounod, and Donizetti.

Elder’s instrumentalists imbue the grandeur of Meyerbeer’s spectacles like the magnificent coronation scene of Act IV and the Westphalian Götterdämmerung of the finale with a power and precision unparalleled in the discography. The conductor’s mastery of the Romantic genre’s diverse styles enables him to navigate the idiosyncrasies of Meyerbeer’s writing, effortlessly shifting between the blockbuster grand opera moments and the delicate lines of Rossinian-inspired lyricism that characterizes its more intimate scenes. His nuanced approach to the music allows the London Symphony Orchestra to convey the work’s moments of exquisite beauty and emotional depth, resulting in a performance that is as impressive in its scope as it is captivating in its subtlety.

Equally as commanding are Elder’s vocal soloists, who capably rise to Meyerbeer’s myriad technical and theatrical challenges. John Osborn here reprises his role as the eponymous prophet Jean from the earlier Essen recording. While his tenor may have lost some of its freshness in the intervening years, Osborn’s interpretation remains complex and dramatically captivating. While earlier recordings and broadcasts of Le Prophète assigned the title role to more modern dramatic tenors like James McCracken, Osborn’s more limber instrument and his stylish, period-appropriate musicianship contribute to a more charismatic and compelling portrayal. For instance, Osborn’s rendition of his first aria, “Pour Berthe moi je soupire,” is lyrical, tender and introspective, whereas his great scene from Act III “Dieu Puissant…Roi du ciel” showcases his mastery of the character’s dynamic range, transitioning seamlessly from the solemnity of the prayer to the heroism of the cabaletta with remarkable finesse.

Even more impressive is Elizabeth DeShong as Jean’s mother Fidès, a role that Meyerbeer conceived for the great Pauline Viardot as the opera’s moral fulcrum. As Orlando Figes noted in The Europeans, “Meyerbeer believed that an opera’s success depended above all on the leading singers’ vocal and dramatic skills. […] In Pauline he had found the range of voice and acting qualities that made her perfect for the all-important role of Fidès.” DeShong, stepping in for an indisposed Anita Rachvelishvili, not only wields an instrument of exceptional depth and astonishing agility that encompasses the music’s incredible demands, but also possesses the scale to meet the opera’s grandeur and the legendary musical and interpretive range of Fidès’s creator.

Her poignant rendition of Fidès’s Act II arioso “Ah! Mon fils” stuns with its tenderness and warmth, while she brings severity and outrage to her confrontation with Jean in Act IV. However, it is perhaps DeShong’s transcendent reading of Fidès’ great dungeon scene, “Ô prêtres de Baal,” that alone justifies the existence of this new recording, as she dispatches the music’s vocal challenges with an overwhelming tide of sound and jaw-dropping vocal agility.

The role of Jean’s lover Berthe is sung with dazzling sweetness and surefooted vocal technique by the young Armenian soprano Mané Galoyan. Although Berthe’s more familiar Act I cavatina, “Mon cœur s’elance et palpite,” is replaced by the alternatively scored “Voici l’heure où sans alarmes,” Galoyan nevertheless sculpts her opening piece with a beautiful sense of line and a fluidity of phrasing that reflects her character’s love for Jean. Later in the opera, she commands both power and agility in the final trio, “Ô spectre épouvantable!”, convincingly portraying Berthe’s seething rage against the corrupted Jean and moving the listener with her character’s ultimate act of suicide.

While Meyerbeer’s antagonists may lack the complexity and depth of characterization afforded to the opera’s leads, the festival cast features musicians with distinctive voices who imbue theatricality to these supporting characters. Bass-baritone Edwin Crossley-Mercer incarnates an oppressive Count D’Oberthal, his rich, imposing voice perfectly suited to the role of the tyrannical feudal lord. The libretto’s sinister Anabaptists, embodied by James Platt’s Zacharie, Guilhem Worms‘s Mathisen, and tenor Valerio Contaldo‘s Jonas, are memorable for the nuanced vocal colorations and characterizations they bring to these thinly drawn villains.

The Palazzetto Bru Zane deserves high praise for sponsoring this collaboration with the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence and bringing to the public this important recording of Meyerbeer’s now rarely performed grand opera. As revivals of the composer’s sprawling works represent a daunting expense for many opera houses, exceptionally cast recordings of such concert performances serve as valuable documents that foster appreciation for his achievements. While Le Prophète in its entirety still presents certain dramatic challenges—the familiar criticism of Meyerbeer’s music being in service to an overall, sensational spectacle can still ring true, particularly in the tedious longueurs of Act III—it is unquestionably a delight to hear the composer’s music performed with the finesse evinced in this recording. The orchestra’s nuanced playing, combined with the stellar cast’s vocal and dramatic portrayals, certainly brings depth and immediacy to Meyerbeer’s opera about religious fanaticism—themes that are increasingly becoming politically resonant in the present day. With the success of this concert version of Le Prophète behind them, one hopes that the Fondation Bru Zane will give the postponed Les Vêpres Sicilienne a similar treatment when it returns to the festival stage in 2026.

Photos: Vincent Beaume