John J. Conner in The Wall Street Journal:

Recently on this page I aimed a number of brickbats at the Metropolitan Opera’s generally unadventurous repertory and the habit of going hog-wild spending money on new productions. Well, the Met has come up with its first new production for this season, a fantastically sumptuous mounting of that not exactly unfamiliar duo “Cavalleria Rusticana” and “Pagliacci.” And the verdict from this corner? Terrific.

The point is that when the Met is good it can be very very good indeed. The problem is that, considering the huge outlays and seasonal deficits, it is not that good that often. Still, when something as successful as this “Cav” and “Pag” comes along, the inclination, no doubt short-lived, is to shout: Damn the expense, full speed ahead.

The hero of the piece is Franco Zeffirelli, the Italian director already represented in the Met repertory with the magnificent production of Verdi’s “Falstaff” and who is probably best known in this country for his recent much-lauded film version of “Romeo and Juliet.” Mr. Zeffirelli has not only directed the entire production (made possible, incidentally, by a “generous and deeply appreciated gift” from Glen Alden Corp.) but also designed the sets and costumes. The result, from any angle, is one of the most visually exciting and intelligently staged productions on any opera stage.

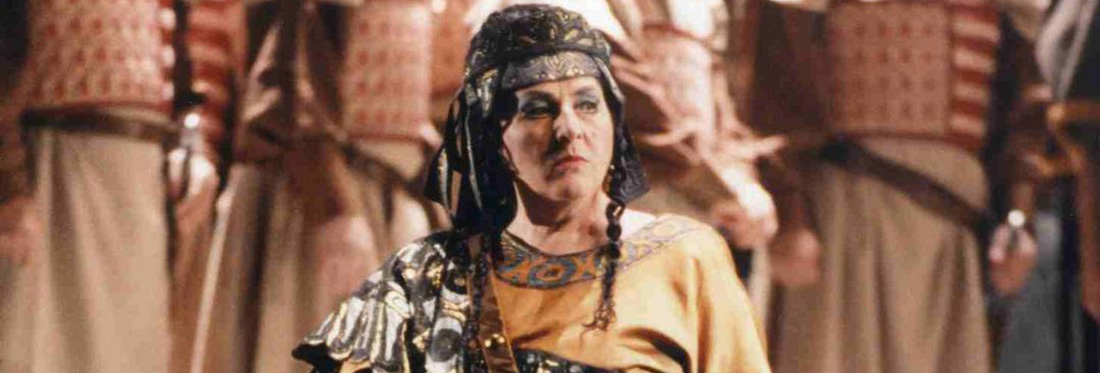

The Italian village set for Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana” is dominated by the facade of a church perched atop a long, steep bank of steps. On either side are typical village houses with balconies on various levels, and in the background can be seen the roof tops of other houses gradually sloping into a valley. When the curtain goes up, the deep blue sky is still dotted with stars, and while the off-stage Turiddu (Franco Corelli) sings of his love for Lola, the betrayed Santuzza (brilliantly acted and sung by Grace Bumbry) sweeps in black shawl about the steps of the church, an hysterical and prophetic angel of death.

Comes the dawn, and the village bursts into bursting life. There are the churchgoers, the vendors, the children. There are the old clothes being tossed over the balcony railings for airing. Most impressive of all, there is the Easter procession into the church, a fascinating and, perhaps to the outsider, horrifying tableau of crucifixes, masked acolytes, incense, ornate canopies, state officials, and of course, the platform bearing the mysterious Madonna. Mr. Zeffirelli obviously is familiar with the scene, and he recreates it here to perfection.

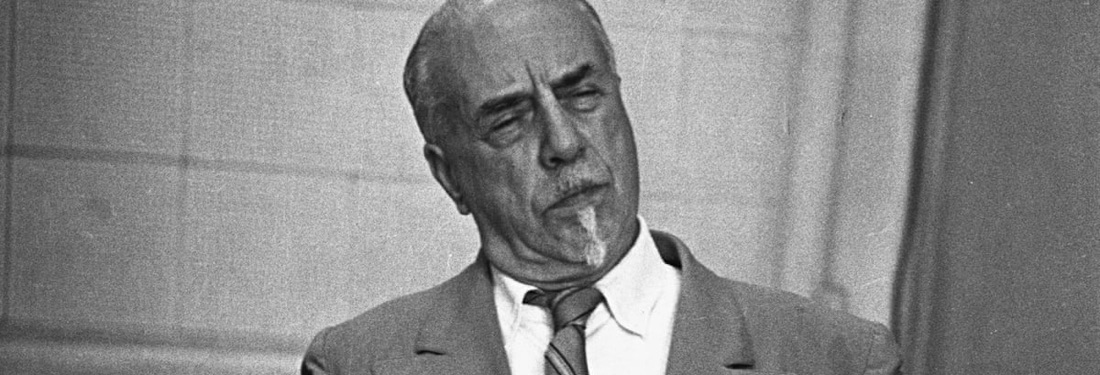

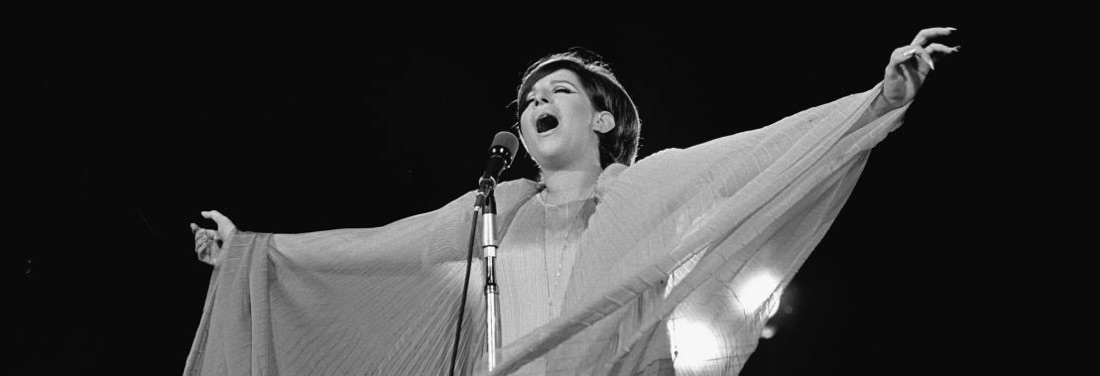

The conductor for the performance was Leonard Bernstein, and although there may be some reservations about some of his slow painstaking tempos, particularly in the famous Intermezzo, there can be no doubt that he had the orchestra pitched to peak form.

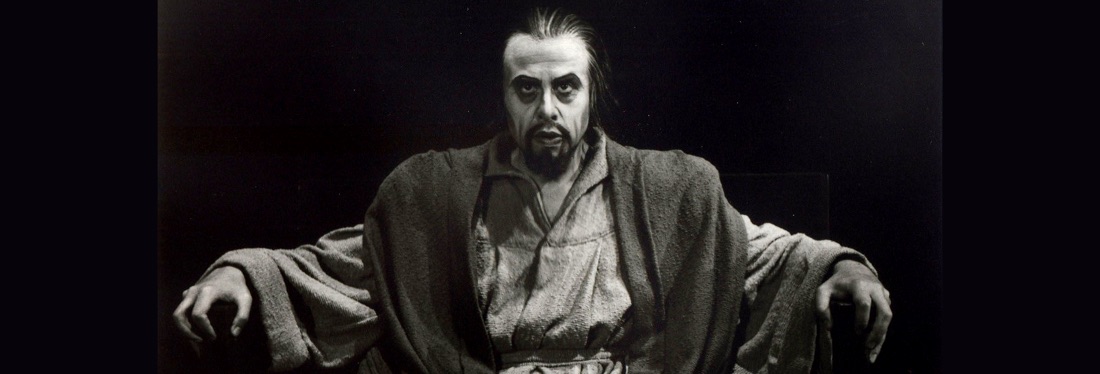

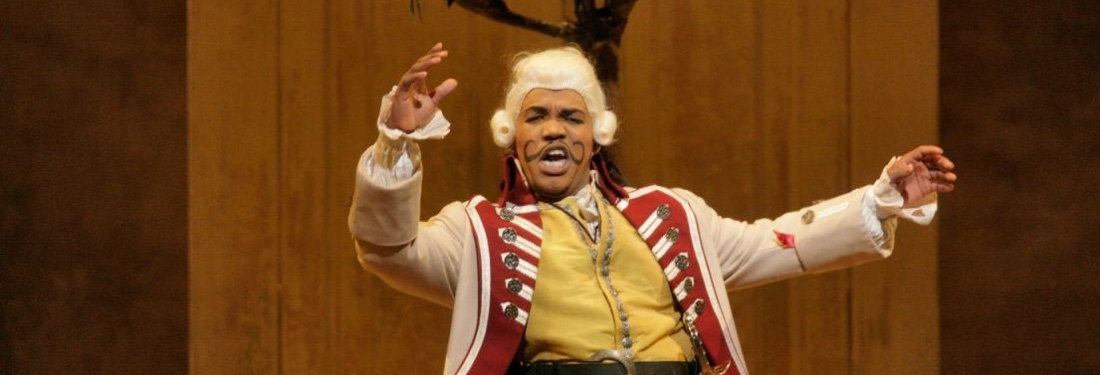

In contrast to the vertical lines of “Cav,” the set for “Pagliacci” is a horizontal of bleakness, a gnarled tree overhanging a field of stone and set against the clouded space of a vast sky. Again, there are the ever-present touches of Zeffirelli realism, the horse-drawn caravans, the real fire for cooking, and the final show that really does attempt to be funny and theatrical, making the townspeople’s reactions believable.

Richard Tucker, celebrating his 25th year with the Met, is surprisingly enough singing the role of Canio for the first time, and it is one of his better performances. Sherrill Milnes is Tonio, and his Prologue provides the singing and acting high point of the Leoncavallo opera. Fausto Cleva does not depart from tradition in his conducting, and he proves nicely that traditional still can be effective.

All in all, the Met has come up with a winner, a super prize for anyone interested in opera, or for that matter, theater.

Born on this day in 1926 soprano Evelyn Lear.

Birthday anniversaries of bass-baritone Karl Dönch (1915), basses Giorgio Tozzi (1923) and Yevgeny Nesterenko (1938), composer Benjamin Lees (1924) and director Elijah Moshinsky (1946).

Comments