Peter Conrad in the Times Literary Supplement:

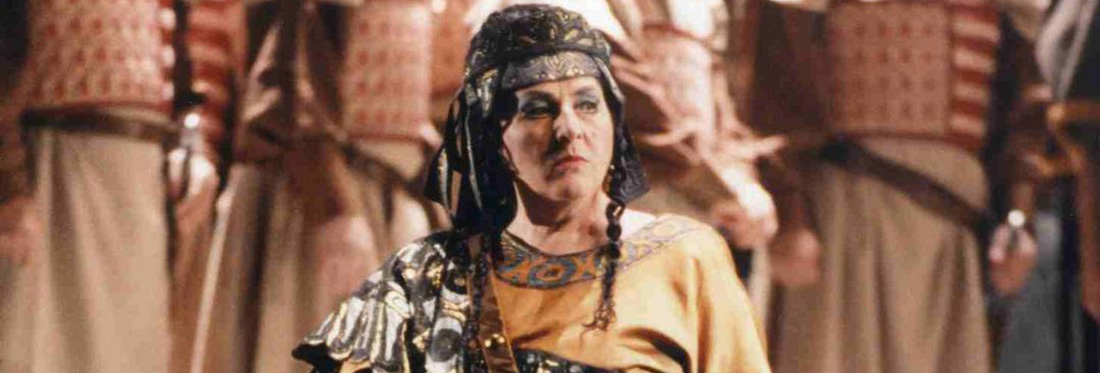

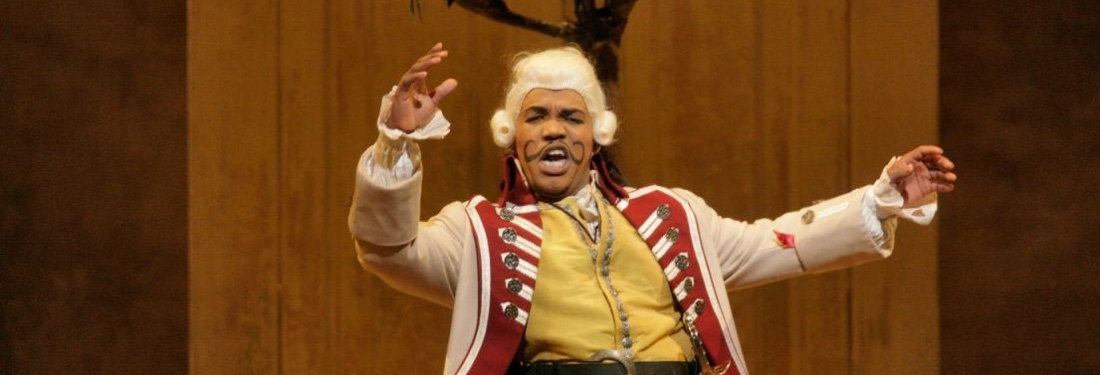

The furnishings for the New York production coil and writhe like the serpentine lines of Art Nouveau. The pillars in Schön’s house are twisted sticks of liquorice, and the painter’s house is a peacock lair outfitted by Tiffany. Handsome though the sets are, they’re contradicted by the extraordinary Lulu of Teresa Stratas, for whom the heroine is emphatically not a venereal demon of the 1890s. Hcr performance attests to Lulu’s innocence, even to her moral purity. She sees Lulu not as a genital automaton but as a person who is uniquely and devastatingly honest, and whose honesty terrorizes a society which preserves itself by euphemism and evasion. Lulu doesn’t edit or censor her thoughts. She confides the truth of her feelings – casually advising Aiwa that she poisoned her mother or enquiring whether the divan where he’s making love to her is the one on which his father bled to death – and her candour can kill.

In a performance of astonishing psychological subtlety, Stratas makes it clear that, though Lulu is a hostage of false morality (she is distressed by the painter’s reproving catechism and when he interrogates her about her beliefs can only whimper “Ich weiss nicht”), she possesses a moral code of her own to which she is austerely true. Thus she welcomes Jack the Ripper as her savage, surgical redeemer. They are natural allies: with his knife he is cleansing and cauterizing a fouled world, just as she chastens the men who try to own her by contradicting the love which they invent to rationalize their need of her. Jack comes to her as a judge and a murdering conscience, and is accepted as such by the Lulu of Stratas, who kneels before him pleading with him to stay, tenderly petting and bribing him until he condescends to kill her. Lulu envies the dead, as her wondering elegies over the corpses of her three husbands proclaim: and she has an intimacy with death which also joins her to Jack, whose profession is the retributive enforcement of mortality. Stratas’s disturbing, touching stage presence perfectly conveys this unearthliness Wedekind called Lulu an “Erdgeist,” but it’s the spirituality, not the coarse admixture of earth, which Stratas – fragile, thin, with a child’s bemused eyes in a ghost’s ancient face – represents. Returning from prison, her hair shorn, wasted, her face grey, she speaks with the detachment and the power of divination of those who have been closely acquainted with death by illness.

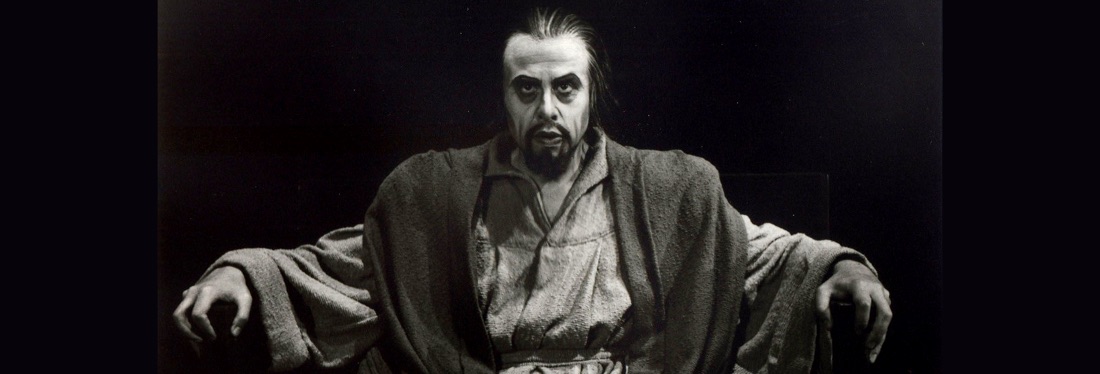

In her voice, too, there’s an eerie ambiguity. Singing its extensions into the upper register are bright and hysterically shrill, scaling pinnacles of irresponsibility, as in her manic coloratura after the painter’s suicide. But when she speaks, as in Lulu’s plangent appeal to Schön in the second scene, she sounds smoky, grave, almost baritonal as if two identities, even two sexes, were housed in that slight, tormented body. The Met’s Schön and Ripper was Franz Mazura. whose intensity as a singing actor matches that of Stratas. Covent Garden’s Schön, Gunther Reich, is a portly, caponized house-husband, and he has been instructed by Friedrich to play the Ripper as a bluff working man, administering the vengeance of a down-trodden class but Mazura’s Schön, his voice edgy with violence, has a glowering rectitude which makes his collapse appalling to watch, and his Ripper is a baleful civil servant, bowler-hatted and carrying a medical kit-bag – an implacable, incisive saviour. Both Stratas and Mazura dwell on that precipice of what Artaud called danger, the tense and risky arena of self-exposure and even self-abuse which is reserved to great and daring performers. Between them, they ignited the Met’s “Lulu.”

On this day in 1956 the Metropolitan Opera celebrated the 25th anniversary of soprano Lily Pons with a special Gala performance.

Birthday anniversaries of poet and librettist Pietro Metastasio (1698), composer Charles Levadé (1869), musical comedian Victor Borge (1909), conductor Rudolf Neuhaus (1914) and mezzo-soprano Nell Rankin (1926).

Photo: James Heffernan / Metropolitan Opera

Comments