David Fox: Isn’t it interesting how much context and the passage of time can change one’s impression? When I saw the original telecast of this Streetcar—a play I knew very well by then—I pretty much rejected it as a non-starter. I doubt I’ve watched more than a few minutes of it since, but looking at it again now—especially coming just days after watching Benedict Andrews’ smugly auteurist, clueless production—I’m inclined to be far more generous. Like you, Cameron, I still don’t find this version fully successful, but director John Erman’s adaptation is an honorable and thoughtful attempt to realize Tennessee Williams’ play, including offering a fuller version of the script, and—boldly, for 1980s television—a considerably more frank and sometimes difficult to watch depiction of the violence. The central performances mostly have strengths and weaknesses, but one jumps out for me as perhaps the best I’ve ever seen. But I’m getting ahead of myself here…

CK: We should probably start by considering the look of the film. In some ways, Erman faithfully follows Elia Kazan’s legendary film in opening up the world of the play to include a fuller picture of New Orleans—for example, the reunion between Stella and Blanche takes place not at the Kowalski flat but in the bowling alley where Stanley bowls. In terms of art direction, the mise en scene captures the steamy world of the 1940s French Quarter with admirable period detail. But some other elements seem noticeably contemporary. Ann-Margret’s costumes—by the celebrity costume designer Travilla, who receives his own title in the closing credits—could just as easily come from the pages of a 1984 issue of Women’s Wear Daily. She looks stunning, but very modern, as if she had to get to her nightclub act after a day of shooting.

DF: I remember when I first saw this, thinking that Ann-Margret would be superb… as Stella. I don’t mean this as a negative comment on D’Angelo, who is often excellent here in that role—but rather that Ann-Margret herself is too corporeal and earthy for Blanche, which—to reinforce your specific point—is made even more obvious as she’s styled to look so much like her iconic persona, including the red hair. (Watching this Streetcar, it’s hard to believe that Carnal Knowledge, the film that gave us some sense of her depth and range as an actor, was 13 years before this!)

CK: Ann-Margret’s talent is evident, but she’s miscast. If Gillian Anderson projected too much nervous instability in the Andrews production we considered yesterday, Ann-Margret only occasionally suggests a woman near end of her rope. This is maybe most obvious in the scene between Blanche and the Young Collector—played here in an early career appearance by Raphael Sbarge—where Blanche seems all too aware of her desire for him, batting her eyes and practically purring.

DF: That scene jumped out at me, too, and probably for the same reason. Taken on its own, it’s quite brilliantly acted, and startlingly different from any other version I know. But, as you say, Ann-Margret is so knowing, so utterly in control of her sexual allure, that my first thought was, “She’s the Mrs. Robinson of the French Quarter!” In a way, this also links to my single biggest criticism of this film—how much of it, and in particular Blanche’s big moments, are rushed. When Ann-Margret takes her time with a speech, she often finds something wonderful in it. But too many times, she dispatches them quickly and moves on. (I assume this is largely a directorial choice, maybe necessitated by running time limits.)

CK: When Ann-Margret and Erman settle into a copacetic rhythm, the results can be very exciting. She’s heartbreaking in what I consider the play’s most affecting scene—Mitch’s ultimate rejection of Blanche, which also represents her last tether to hope—and intense in Blanche’s confrontation with Stanley. Ultimately, she pushes too hard into unhinged madness in the final scene—an unpleasant obviousness that Erman counters with too much suggestive music and canted camera angles.

DF: More generally, I’m not much won over by Marvin Hamlisch’s score, poised somewhere between the ragtime-inflected work he did so effectively in The Sting, and the schmaltzier kind of writing he was perhaps even more celebrated for.

CK: Music is so important to Williams’ methods of storytelling that it’s often written into the stage directions or the dialogue. The composers who understand that—Paul Bowles in The Glass Menagerie, for example, or Alex North with the jazz-inflected score for the original Streetcar film—tend to deliver soundtracks that underline moments and themes with subtlety and quiet grandeur. Hamlisch, on the other hand, supplies big, obvious motifs that knock the listener over the head with subtext.

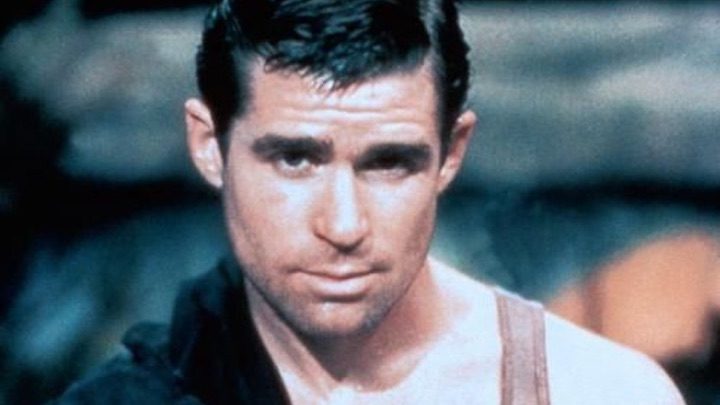

DF: Agreed. I’ve mentioned my criticism of Erman’s brisk pacing in too many scenes, which I think undercuts Williams’ poignancy and gravitas. Both those qualities are also lacking, I’m sorry to say, in Treat Williams’ Stanley, which is appealing as all get out. The problem is, that’s hardly the takeaway quality you want in a Stanley under any circumstances, and much less with a Blanche as knowing as this one. Williams’—Treat, not Tennessee—is especially cruelly exposed here in the famous cries of “Stella!” It doesn’t help that Erman has chosen such similar camera angles and compositions to those of Kazan’s film. Of course, Brando is unforgettable here—but we needn’t be reminded of it quite so literally.

CK: Treat Williams does hit his stride in the confrontation scene—and as you already mentioned, it’s admirable that, for a network television movie of its time, the moment is treated with all the brutality and violence intact. I also found it interesting that he presents Stanley as a fully Southern character, Creole accent and all. But it never quite comes together, and that likability factor has a lot to do with why. On the other hand, Randy Quaid may be the best Mitch I’ve ever seen—partly because there is a darkness to his performance that I think is ultimately right, considering how he treats Blanche.

DF: Indeed, and I agree completely about Quaid: his is the performance I referred to at the beginning. This is a telling reminder that, before he went full-on Ruby Ridge, he was a hell of an actor. Here, he has something close to Karl Malden’s pathos and charm, but also an unexpected streak of cruelty that really cuts deep in his final scene with Blanche.

CK: In terms of opening up the story, though, I hated that Blanche’s narrative about her husband’s homosexuality and suicide was moved to the back of a horse-drawn carriage on her date with Mitch. At this point, Blanche is still concerned with propriety and appearances—it strains credibility that she would tell such an intimate, potentially damaging story in public, mere feet from a stranger.

DF: Yes. Reading this over, I’m realizing again what a mixed bag this TV movie is—some moments fail to come off, but other aspects work exceptionally well. One important one for me that’s a real plus here—Ann-Margret and D’Angelo are more convincing as sisters than any other pair I can think of, and that’s pretty important. On her own, D’Angelo I think is also one of the better Stellas I’ve seen, and her considerable allure makes it clear why Stanley would be drawn to her.

CK: D’Angelo certainly conveys a harder edge than most Stellas, which I think is absolutely appropriate and thrilling. I also want to single out the wonderful character actress Erica Yohn, who brings a real campy sensibility to Eunice Hubbell.

DF: For me, she’s the most memorable Eunice after Peg Hillias. But that’s for another write-up—yes, Cameron?

CK: I’ll have to consult the Napoleonic Code.