First, Nina Stemme had to ask for indulgence due to a rehearsal knee injury as Elektra. Then, Albina Shagimuratova opened as Violetta in La Traviata to great acclaim, only to fall to acute laryngitis, missing three performances. She’s back now, but her Alfredo, Giorgio Beruggi, missed a performance covered by Mario Rojas.

And at the March 2 opening of Handel’s Ariodante, mezzo Alice Coote had to cancel the title role due to the flu.

Happily, I attended yesterday’s matinee, though a frisson went through the audience when Anthony Freud appeared at the curtain with his microphone. We were relieved to hear that Ms. Coote would sing, but she asked our indulgence as she was still recovering.

The announcement was gratuitous—she was in splendid voice, and had the technique, stamina and passion to deliver the role’s seven (!) arias without a hint of difficulty. In fact, the entire cast’s singing was exemplary.

Handel’s melancholy opera seria from 1735 has been reset by British director Richard Jones (and revival director Benjamin Davis) in a startling and intriguing way. The concept changes the courtly baroque setting to 1960s-70s Scotland, on a remote island dominated by a neo-Calvinist sect, with a community based on fishing and wool.

The theme of the production is clearly misogyny, with women being degraded and relegated to the task of “helpers” to their male counterparts. This makes some sense considering the operatic plot.

The story is that of frequent operatic conventions: After much distress as Ariodante contemplates suicide and his brother Lurcanio tries to stop him, the truth of Polinesso’s treachery is found out, he is killed in a duel with Lurcanio, and the lovers reunite in an ecstatic duet… but, in this production… not exactly.

Much of the problem concerns Jones/ Davis’ interpretation of Polinesso, turning him into a cartoonish, sexually perverted villain. Polinesso licks a strand of Ginevra’s hair and sniffs her undergarments, removing his minister’s robes and revealing tight jeans and tattooed arms.

But worst of all is his abuse of loving Dalinda. While Lurcanio is singing earnestly in the meeting hall trying to save his brother’s life, Polinesso is seen in Ginevra’s bedroom (having “roofied” her into unconsciousness) committing a brutal and violent rape of Dalinda, leaving the poor girl bleeding and bruised.

This scene, besides the egregious split focus (which scene are we supposed to be watching?) could not be more gratuitous and sophomoric. And then, if this wasn’t enough, Polinesso produces Tom of Finland-ish drawings of well-endowed male nudes, hoping that they will be found by Ariodante and the King as Ginevra’s pornography stash.

It is a tacky, totally unnecessary bit of business that cheapens the whole proceedings.

The best of the staging is provided by brilliantly manipulated stage puppets designed by Finn Caldwell, dance music at the end of each act is used for this puppetry, representing the community and the characters’ mental states.

At the end of happy Act One, puppets of Ginevra and Ariodante meet, love, and marry, followed by multiple (!) births. At the end of Act Two the troubled community changes the Ginevra puppet into a mini-skirted pole dancer. This conceit is effective and moving.

Jones and Davis also alter the opera’s traditional ending of Ariodante and Ginevra’s reconciliation and redemption. Here, as in Ibsen’s Nora in A Doll’s House, Ginevra is infuriated by her father’s anger and Ariodante’s doubting of her fidelity. She packs a bag, leaves, and thumbs a ride away from the island at the curtain line.

Miss Coote showed remarkable commitment to text, elegant phrasing, and managed all the deep emotion of the aria while maintaining Baroque style. Her joyous aria “Dopo notte” in the final act was infused with genuine love and joy.

Debuting soprano Brenda Rae as Ginevra started a bit slowly, her entrance aria “Vezzi, lusinghe, e brio” a bit pallid, but she quickly recovered in the florid extravangance of “Volate amori”, gaining in confidence. Her performance soared both in emotion and remarkable technical precision, her bright soprano always expressive.

She was matched by the superb Heidi Stober as Dalinda, loving and innocent in her Act One aria “Il primo ardor”, and finally and furiously expressing her betrayal by Polinesso in Act Three’s “Neghittoisi, or voi che fate?” (Lazy heavens, what will you do now?)

Kyle Ketelson struck a stentorian, kilted figure as The King, using his plummy bass-baritone to touching effect both in his fatherly love and his fury at Ginevra’s perceived sin.

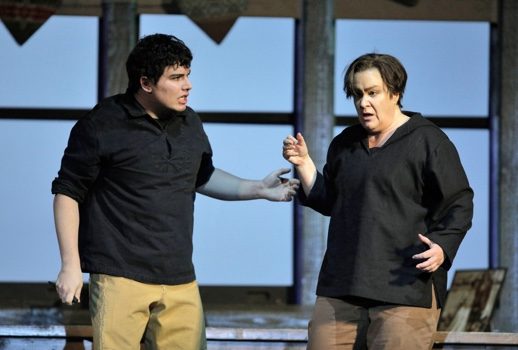

Countertenor Iestyn Davies sang remarkably well as Polinesso, throwing himself fully into the sleazy character both vocally and physically, slithering snake-like in his perverse intentions. His singing, too, was exemplary, tossing off extravagant phrases with ease and purpose.

And the real find of the performance was first-year Ryan Opera Center member Eric Ferring. This young man has a florid, plaintive, juicy tenor that we’re going to hear a lot of in the future. His Lurcanio was a fully formed characterization, sung with style and verve that betrayed his young age. This is a young singer to watch!

Baroque specialist Harry Bicket led a precise, moving reading of Handel’s florid and detailed score from the Lyric Opera Orchestra, and the “small version” of the Lyric Opera Chorus sang and acted with perfect precision and personal characterizations.

It is a shame that directors Jones and Davis took a potentially fascinating update and just went too far, way too far. And the ham-handed obvious use of Biblical passages denigrating the role of women turned a worthy social theme into a travesty.

Photos: Cory Weaver

Comments