The opera was a failure at its premiere on that same stage in 1868: considered avant-garde and too Wagnerian for its time, it provoked riots and was cancelled by police after its second performance. Giuseppe Verdi, for whom Boito wrote the libretti for Otello, Falstaff, and the 1881 revision of Simon Boccanegra, commented, “He aspires to originality but succeeds only at being strange.”

Mefistofele underwent substantial changes over the next eight years: Faust, originally a baritone, was made a tenor, a great deal of music was rethought, and approximately one third of the score was cut (one of the original complaints was the opera’s running time). By 1876 Boito had fashioned a work which garnered successful productions throughout the Continent, and reached the UK and the USA in 1880.

While the opera never quite made it into the standard repertoire, the emergence of a great basso has often been the cause for a new production: the title role’s interpreters have included Feodor Chaliapin, Nazzareno de Angelis, Boris Christoff, Cesare Siepi, Norman Treigle, and Samuel Ramey. After an absence of 73 years, the Metropolitan Opera presented the opera as a vehicle for Ramey in 1999.

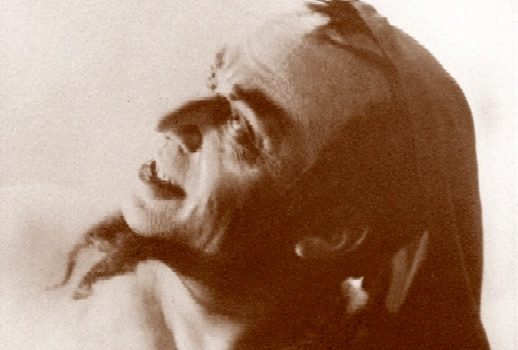

Between 1906 and 1938, de Angelis sang more than 500 performances as Mefistophele. In 1931, at the age of 50, he recreated his legendary portrayal for Columba Records, his only complete opera recording.

Other roles included Oroveso in Norma, Creon in Medea, Il Gran Pontefice in La Vestale, the title role in Gioachino Rossini’s Mosè in Egitto, and Sparafucile; he also created the role of Archibaldo in Italo Montemezzi’s L’amore dei tre re. Although his career was centered in Europe, he was engaged in Chicago and Buenos Aires in the 1910s.

Antonio Melandri, trained as an oboist, was a late-bloomer, making his debut at 31 as Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor. With a career that took him throughout Europe and to Buenos Aires where he enjoyed particular success, he found his voice darkening and began to take on dramatic roles such as Otello and Sigfrido in Il crepuscolo degli dei.

One of his specialties was Turridu in Cavalleria rusticana, which he recorded for Columbia in 1929 with Giannina Arangi-Lombardi, and later performed with Pietro Mascagni conducting a legendary performance, recorded live in 1938, with Lina Bruna Rasa, which can be found on my Mixcloud site. His only other complete opera recordings, also for Columbia and the forces of La Scala, are Ernani and Fedora.

In his indispensible book The Last Prima Donnas published in 1982, Lanfranco Rasponi placed soprano Mafalda Favero in the section devoted to “The Small Voices that Traveled Far” along with Bidù Sayão and Rita Streich. Favero’s success lay in her dramatic abilities to so embody a role that the lightness of her voice could be forgiven in heavier repertoire such as Eva in I maestri cantori di Norimberga (the role of her 1929 La Scala debut under Arturo Toscanini), Charlotte in Werther, and Adriana Lecouvreur. Margherita in Mefistofele was among her first assignments at La Scala, where she performed 27 roles across more than a quarter of a century.

Mimí was one of her favorites, a role which served as her Met debut in 1938 aside another debutant: Jussi Björling. Among a large and varied repertoire, Favero appeared in world premieres of operas by Franco Alfano, Riccardo Zandonai, Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, and Mascagni. Retiring at age 51, she claimed that Cio-Cio-San took five years off of her career. Favero’s colleague Giulietta Simionato commented, “She gave away a great deal of herself – more than was good for her – but the result was extremely moving.”

Arangi-Lombardi is one of your alte Jungfer’s all-time favorites based on her few complete recordings: the above-referenced Santuzza, La Gioconda, and Aida, in addition to this week’s Mefistofele. Beginning her career in 1920 as a mezzo, she evolved into a true spinto soprano and had a second debut three years later. In 1924 she was invited to join La Scala as Elena in Mefistofele under Toscanini. Other notable roles included Turandot (of which she gave the first performance of the opera in Australia), Julia in La Vestale, and Lucrezia Borgia. Quitting the stage in her late 40s, she became a renowned teacher with Leyla Gencer among her star pupils.

There exist more suppositions than facts about the life and career of conductor Lorenzo Molajoli. Born in Rome, he studied at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia and began his career in 1893 at age 25. He seems to have been active as an operatic coach in North and South America, South Africa, and various provincial Italian houses

He was certainly involved in the 1912 season at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, when he wrote to a friend about a falling-out over the interpretation of Manon between Toscanini and tenor Giuseppe Anselmi, as well as criticizing another conductor of the season, Bernardino Molinari. Rumors exist that Molajoli conducted at La Scala between the two World Wars, but there is nothing to substantiate them.

In 1926 the UK-based Columbia Graphophone Company [not a misspelling] hired Molajoli as its house conductor for recordings made in Italy, including its expansion into the new technology of electrical recordings of complete operas. Between 1928 and 1931, Molajoli made recordings of 20 complete (or nearly-complete) operas in addition to orchestral works and aria discs.

Molajoli was often pitted against his contemporary Carlo Sabajno, who held the same position for The Gramophone Company, which was also using the La Scala forces for recordings on its HMV label when the rival companies merged in 1931 to form EMI, sometimes with overlapping repertoire.

Critics cite Molajoli’s conducting for its sure sense of style and unanimity of ensemble, especially between orchestra and singers. Many of his recorded performances possess a fiery sense of drama, as well as frequent headlong tempi which give his readings an engaging and appropriate sensation of forward propulsion. This recording of Mefistofele is considered one of his best.

If you aren’t familiar with Mefistofele aside from Margherita’s “L’altra notte,” I would like to suggest this performance is as good as any others on record. Sit back, relax, curtain up: Prologo in cielo…

In case you missed my mid-week posts at Mixcloud, you can find a lovely Schubert Liederabend by Gerald Finley from Schwarzenberg in August, and my memorial tribute to Johan Botha: Act I of the 2014 Bayreuth Die Walküre with Anja Kampe and Kirill Petrenko conducting.